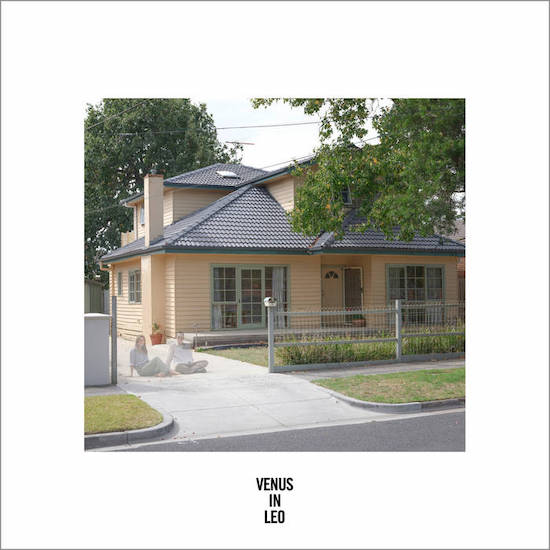

In his review of HTRK’s 2014 album Psychic 9-5 Club for the Quietus, Chad Parkhill noted that the in comparison to HTRK‘s previous releases, the album took a sonic and aesthetic shift in the way that the sounds dealt “mundanely supernatural”, how the realm of the dark, the gothic and the uncanny has been folded and squeezed into the flattened landscape of modern life, where the immaterial and the otherworldly is as fallible and banal as the material and organic. It’s almost as if the band have taken this to heart with the cover of their new album Venus in Leo, which depicted the utter normality of a nondescript and faded house in anywheresville USA, with HTRK’s Jonnine Standish and Nigel Yang sitting out in front, faded out to near non-existence, with the aura of suburban normcore ghosts.

This image helps to set out and express the world of Venus in Leo, one where HTRK’s music has undergone a further refinement and distillation that began with the grinding slowcore and no-wave blankness of Marry Me Tonight, towards the crunchy maudlin electronics and the urban numbness of 2011’s Work, Work, Work, and undergoing a further transformation to the wet, fuzzy neon dub in 2014’s Psychic 9–5 Club. But with Venus In Leo, Standish and Yang have stripped everything in their music back almost beyond the bone, to the bare abstract essentials of what could be called rock. The rhythms provided by a skeletal, metronomic drum machine almost disappear into the shadows while Yang’s fragile guitar lines flicker and waiver around a fading light. It’s ghostly transparent rock minimalism to point of vanishing before your ears and eyes. Even when they take a track such as ‘Hit ‘Em Wit Da Hee’, a cover of the Missy Elliot song dismantles the vitality of the original’s tuff RnB slow groove and replaces it with a gothic funereal waltz.

And yet, HTRK still retain a hypnotic, beguiling presence. Standish’s vocals still retain a distinctly anaesthetized anti-raunch pallor of tone, but now they provide the emotional bedrock that centres the whole album. There is now a sense of yearning that appears in her delivery that can be heard in several moments in Venus In Leo such as in ‘Mentions’ when she softly pleads against the lack of human contact in our digital world (“even with this soft obsession / It’s not enough attention for me / Even with another mention / It’s not nearly physical enough”), or the cooing intimacy on ‘You Know How to Make Me Happy’ where she softly sings “So we get caught in the ocean / And you tell me I’m the favourite one / baby come on / My head will never leave the sky”.

There are other aspects of HTRK’s music that are still present after these years. The circular, looping structures and drifting pace and manner of their songs are still evident, but on Venus in Leo this is accentuated by Yang’s liberal use of echo and looping effects, so that every scratch of the string, every brush with the pick folds back into the songs, so that from almost nothing comes a gradual expansion of lush sounds.

By creating feats of sounds and emotion from such meagre rations, HTRK feel at odds with the accelerated cries of MORE and intensified yet increasingly precarious nature of social relations that passes for a contemporary society. With their minimalist manner and the repressed tension between cohesion and dissipation, HTRK have moved from the early post-punk influences of Joy Division, Public Image, and Cabaret Voltaire, and instead have glided into a continuum of aesthetics pioneered by the likes of Scritti Politti, the Raincoats, and most importantly, These Marble Giants in the way they exuded a delivery and style that was austere and stark but hinting at a vastness of feeling and intensity underneath. Their music, while not overtly political with a capital P, expressed the emotional reality of people’s lives at the time, living lives of quiet desperation under the looming thumb of Thatcherism in prosaic and brutally insipid new towns, a waking nightmare of non-places in the form of precincts, arcades and motorways, but lacking any sense to community or cohesion.

With HTRK, that quiet desperation has turned into a mute scream of crashing mental unrest and emotional disquiet, as people are rendered physically numb and inert, but internally agitated, overwhelmed by sensations derived from the screen burn of too much information and stimulation. Many of the personas in HTRK’s world are left with a free-floating sense of dread and restlessness, settling into a jagged, yet exhausting euphoria. HTRK’s music points to living in a world where you are not allowed to be bored but your environment has become a boring cultural dystopia. Like These Marble Giants, the world of Venus in Leo also shuns the bombastic and the hyperbolic, instead valorising the small snapshots of life and the personal. Songs such as the title tracks ‘Venus in Leo’, and ‘Dream Symbol’ has Standish display a reflexive inward turn into her past and subconsciousness that mixes the confessional with a dream-logic opacity, that contains the sense of the familial and familiar (“My mother always says you don’t get that from me / You take it so personally”), with the troubling (“I’ve been on the sensitive side / Feeling the changing of the tides / And it doesn’t make sense at the best of times”).

With Venus in Leo, HTRK have, in a sense, come full circle from their beginnings over a decade ago, having sloughed off a fair amount of emotional and musical baggage on the way. What’s left is a sleek, stealthy resilience which at times goes against the fragility of their sound. They are now making music that, thanks to its lack of grandiosity and ornateness, has a seeming air of distance. It could almost pass through you unnoticed. But they leave traces in your brain that linger and slowly burn inside of you, long after you’ve stopped listening.