Soul Jazz Records has struck the right note in reissuing this 1979 live recording from the late California pianist Horace Tapscott. Slowly but surely his unique style as a player, bandleader and teacher is being acknowledged.

Tapscott’s autobiography, Songs of the Unsung, was published in 2001, two years after his death, and helped reveal the full scope of his life as a Los Angeles jazz stalwart. While in 2017, filmmaker Barbara McCullough released a documentary about his life called Horace Tapscott: Musical Griot, showcasing 17 years of footage that she had collected. Both helped to shed light on the man who served as a household name for jazz players – such as sax legends David Murray and Arthur Blythe – who cut their teeth in Watts.

Yet Tapscott’s biggest endorsement has come more recently from another trailblazing Los Angeles saxophone player: Kamasi Washington. His meteoric rise has prompted a recent explosion of interest in the Los Angeles jazz scene. And while players such as Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Frank Morgan and Curtis Amy need little introduction, Tapscott deserves greater recognition.

With little interest in the trappings of the mainstream music industry, Tapscott (born 1934 in Houston, Texas) turned his attention to the Watts community, mentoring three generations of local musicians and fostering a radical self-dependence for his beloved neighbourhood. His commitment was summed up by Washington – raised in nearby Inglewood – who said: “I love Horace Tapscott! I love his music, his philosophies, and everything he did for the community that I grew up in.”

Tapscott founded the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra in 1961 to preserve and spread African and African-American music. It eventually became the Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension, a group that not only performed musically but was active in the civil rights movement, youth education, and community programmes. The Arkestra survived many of the changes and tumult in LA, and specifically Watts, most notably the 1965 insurrection and the 1992 riots.

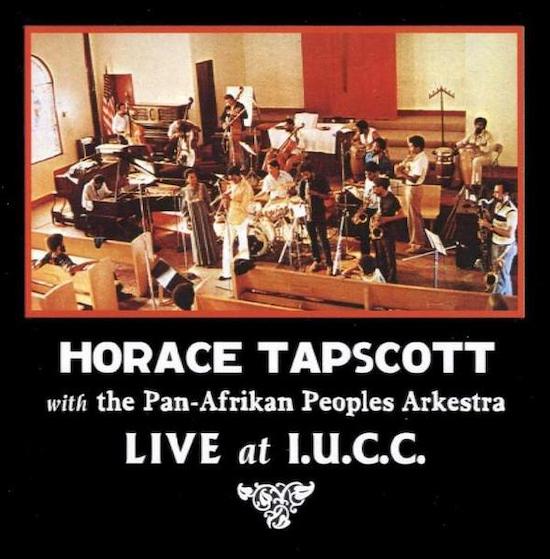

While his political and spiritual principles were unwavering, his music reveals some glorious contradictions. On this church hall date, Tapscott presides over a large band which convincingly executes some fascinatingly cerebral and strident jazz. It’s cut from the same mould as a Mingus big band date – but instead of the bombastic clowning around, Tapscott’s riffs and runs on the piano are difficult to pin down and strangely ethereal.

He kicks off the gig with a pensive repeating line on the modal tune ‘Macrame’. Backed by just a bassline and the superb loose-limbed drumming of Everett Brown Jr, the song unfolds to reveal its horns. He affords ample time to its soloists as he vamps supportively in the background. Later, Tapscott’s staccato piano stabs out the opening riffs of ‘L.T.T.’ which could be mistaken for a Kamasi jam. As a live album experience, it’s both deadly serious and supremely uplifting. And by the end, it’s clear that it offers a lifetime’s worth of musical ideas within Tapscott’s spiritual jazz.

All seven of the tunes stretch into double digits, with ‘Village Dance’ hitting the 26-minute mark. The recording picks up the hall’s huge ambience – for better and worse – which makes it an evocative listen. “It was to Horace’s liking, the rawness of it, the way the sound reverberated and filled the space,” said LA jazz scene author Steve Isoardi. Tapscott said he saw the Immanuel United Church of Christ hall in a dream – and it fulfils Tapscott’s commitment to playing challenging jazz in accessible surroundings for the benefit of the community.

It’s difficult to compare this large-scale live recording to anything else in Tapscott’s limited discography as he recorded only one album in the 60s, and only a handful of small group dates in the 70s. It’s also the only recording of the full Arkestra in concert. Nevertheless, Tapscott would surely be surprised to see his profile on the rise so many years later – but the recognition is certainly deserved.