"On the outskirts of every agony sits some observant fellow who points" (Virginia Woolf, The Waves)

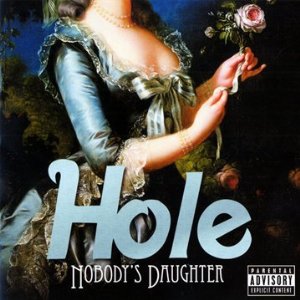

With Nobody’s Daughter, Love’s first release since 2004’s solo album, America’s Sweetheart, the woman who surgically erased her familial features brings her long war against heredity to record once more. Love’s work habitually contests notions of family: where Pretty On The Inside pitched itself against a list of maternal archetypes, using the language of alienation to construct new, liberating sets of possibilities, and Celebrity Skin sought to present Love as an autochthonous creation of American ambition, Nobody’s Daughter reiterates Love’s case for self-definition beyond the bounds of family trauma (1).

That’s not to say she states her case clearly. Even ignoring the egregious sexism that dominates much critical reaction to her work, life, and point of view, Love is a tough read for many, precisely because of her insistence on defining her own context. No Love performative – and within that term I group her records, her diaries, live shows, interviews, and the many ways Love has found to interact with her fans, including, over time, her websites, Facebook page, and Twitter feed, as well as her occasional, mercurial patronage (Love understands very well the risks and benefits of recruiting from the fan pool) – comes without a lengthy bibliography of literary, musical, pop-culture and autobiographical references. Simply in terms of a demonstrable will to seed her own surrounding discourse, Love is almost peerless (2).

These days, to borrow her tendency to floral metaphor, her discourse is wilting around her. Her former peers, those women in rock, are barely still relevant within their former defining context; as Love predicted, “one by one, they fall with no sound” (3). Her last remaining touchstone is the reticent PJ Harvey, whom Love has been careful to cite in the past. Since the utter humiliation of her hospitalisation and imprisonment, and the subsequent failure of judgement that was America’s Sweetheart, she is less apt to invoke such consummate female musicianship in the service of her point of view, locating this new record within a more masculine context. Classically Lovian was the decision to acquire a ‘Let It Bleed’ tattoo and make much of her use of Electric Lady Studios for the writing and rehearsal of this album (she was similarly insistent on Neil Young and Led Zeppelin as early references for Celebrity Skin). In the wake of her decision to duck the critical karma of America’s Sweetheart by reanimating the Hole moniker for this new project, and facing public criticism from former bandmates Eric Erlandson and Melissa Auf Der Maur for doing so, Love invoked a string of dudeish bandleaders in her defence, including Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails and Billy Corgan of Smashing Pumpkins, pointing out the sexism of a critique that does not recognise women songwriters as auteurs. Love seems perfectly equanimous about her decision, occasionally and hilariously referring to her bassist as ‘Invisible Dave’ onstage (in fairness, Quietus readers, I have two words for you: The Fall). Nobody’s Daughter, having dispensed with Love’s family tree, argues that Hole too is more than its DNA.

This point of principle notwithstanding, there’s no pretending that the writing partnership at the heart of the new Hole, that of Love and her skinny, Skins-y guitarist Micko Larkin, previously of insignificant prancers Larrikin Love, is not sometimes uncomfortable. Their partnership is very much foregrounded: the record begins with three Love/ Larkin tracks, but the Verve and Oasis – and their less plodding progenitors, the Kinks – are simply not fitting influences for the former Athena polites of Seattle and LA, the woman who penned both ‘Northern Star’ and ‘Malibu’. ‘Nobody’s Daughter’ and ‘Honey’ in particular recall the very worst of Britpop’s rockist reminiscences. Larkin borrows heavily from Oasis for the former, in his chosen chords and structure, and Michael Beinhorn’s overladen production agrees. Love occasionally joins them, particularly in the "astounding us/ surrounding us" couplet, which is Gallagher through and through. ‘Honey’ begins with those same bright-sounding acoustic chords that dominated the UK album charts for a decade, but Love’s vocal choices are far more characteristic here – the octave interval for emphasis, the syllabically overladen line carried by her exaggerated vowel sounds, her grit, her growl (4) – though she does slip in an unfortunate “live forever” in the middle eight. It’s not so much the Britishness of the reference set which is the problem; Love has a lengthy relationship with what she calls ‘Brit deathrock’, the New Romantic pop in which she immersed herself as a teenager, before travelling to Liverpool to absorb its dubious glories first-hand. But phrases such as ”live forever” have such weight in Love’s own context that pairing them with Oasis figures seems a feint, an afterthought, and an odd choice for an artist usually so insistent on the primacy of the riff. A Britpop record from the former queen of grunge (5)? That joke [really] isn’t funny anymore.

When Larkin is not dislocating Love from her proper context, the record improves considerably. ‘Skinny Little Bitch’, another Love/Larkin track, finally realises Love’s long ambition of penning the quintessential radio-friendly unit shifter (and in doing so ironically recalls the other LA rock singles band, the Foo Fighters). The lyrics (“you staggered here on broken glass/ so I could kick your scrawny ass”) are just dumb enough for radio, though with Love, dumb always implies restraint, and like many of the tracks on this record, ‘SLB’ did have an earlier, more complex incarnation. Critics keen to point out the resemblance between the SLB character and Love’s own worst excesses should be aware that Love characteristically reads herself into her characters to add empathy and depth. On this record, however, empathy gives way to blame, and Love implicates herself in her most vicious diatribes. Miss World, Love’s gentlest creation, reappears here as Miss Begotten in ‘Nobody’s Daughter’; Pee Girl, the protagonist of ‘Softer Softest’, is reread here as the SLB. In ‘Loser Dust’, ostensibly a rant, Love’s chant-like vocal slyly references ‘Loaded’, Pretty On The Inside‘s brilliantly ambivalent hymn to doing drugs with one’s significant other (given the enormous struggle she has had with drugs, Love can be forgiven for having less and less patience with her former Neely O’Hara-isms). In the elegant and stoical ‘Never Go Hungry Again’, Love decides “it’s time for me to be a man”; Hole fans will remember very well the mix of rage and envy this phrase implies. The late-period Hole single of the same title, a litany of patriarchy, insists “just rape the world because you can/ that’s what it takes to be a man.”

Lyrically and thematically, then, Nobody’s Daughter deserves its place in the Hole discography. It is, however, perceptibly the product of two distinct song cycles: one immediately post-rehab, written on the acoustic guitar Love claimed saved her life, developed and given shape by Linda Perry, Love’s longtime foil and the reassuring voice behind her disastrous solo album; and another, more recent cycle, the product of more active collaboration, largely with Larkin and Billy Corgan. Large though the appetite may be to witness Love’s long suffering, in the end product the latter cycle outstrips the former in terms of quality and judgement; the majority of the post-rehab cycle was co-written with Perry, and suffers for the association. Compare ‘Letter To God’, written by Perry alone, with Love’s self-penned bonus track, ‘Never Go Hungry Again’: each tries for a confessional tone, but only ‘Letter To God’ overshoots. Its absurd rhymes (“I’m so sorry I’m so weak/ and I turned into a freak”), its bleak portrayal of the bottom, are unconvincing inasmuch as they are ill-managed. By comparison, ‘Never Go Hungry Again’ is simple and sparse, with an enviable economy of phrase and figure, and the voice, effortlessly describing the indescribable pain of failure (“and my wig’s on crooked, and I got no shoes; I rock back and forth, and I wait for you”), retains its dignity as a result. This track is a worthy successor to ‘Northern Star’ (to which the phrase “and I wait for you” refers) and ‘I Think That I Would Die’, Love’s earlier scrutiny of the unbearable.

After the romp of ‘Skinny Little Bitch’, the albums’ high points are the ingenious inside-out pop of ‘Samantha’ (which, despite a certain clumsiness of line at times, at its best recalls the glorious call-and-response of the Hoodoo Gurus’ ‘Bittersweet’, a track Hole covered on the Use Once And Destroy tour), and the elegiac ‘Pacific Coast Highway’. ‘PCH’ adds the sad postscript so clearly expected by Californian paeans ‘Malibu’ and ‘Celebrity Skin’: Love invites us to compare her earlier hopes of “miles and miles of perfect skin” to their actualisation – the “miles and miles of regret” that bring the song to a close. The only sour note is, again, a nostalgic one; the verse apes the three-chord motif of Celebrity Skin single ‘Boys On The Radio’, a song so perfect that ‘PCH’ suffers a little for the comparison. It’s here that Erlandson is most missed, for his guitars that crash and burn, that fold and fade so slow. When Larkin tries for the kind of effortlessly comely figure that Erlandson would use to bridge between song parts, his proportions are relatively clumsy. This unfair comparison aside, the song is genuinely lovely, in particular the outro, which recalls the magnificent ‘Reasons To Be Beautiful’, Celebrity Skin‘s standout track.

Nobody’s Daughter is not the triumphant return Love so desired, but there’s just enough Love performative here to enliven its weaker moments, and the cast of characters (including Scarlett O’Hara, Marie Antoinette, Anne Boleyn, the Skinny Little Bitch, Samantha, the ghosts of several lovers, and Love herself) is generally well-drawn and compelling. The later-written songs are stronger, which is hugely encouraging for any forthcoming records. The album retains the hunger and the anger of mid-period Hole, while losing some of the miasma of late-period, and crucially, it does not flinch from examining Love as character; it allows her to assume a certain knowing distance from her own suffering and achievement, in a way she hasn’t managed since Pretty On The Inside. At this point in her career, it’s the best seat in the house.

- This record revives Love’s curse of the album title; months before its release, Love again lost custody of her daughter, Frances Bean, to her former mother in law, Wendy O’Connor. Her recent Mother’s Day tweets on the subject were absolutely heartbreaking.

- Almost. Love long concealed her enormous debt to that other self-mythologiser, Morrissey, but of late has been covering the more gruesome Smiths songs in Hole live sets.

- You remember them, those feminist musicians – it was decades ago now; are they still relevant within the rock context? Gwen Stefani: clothes line, proto-Gaga queered-up pop videos, nope. Amanda Palmer: now showing her Siamese Twin act at a circus near you, nuh-uh. Kat Bjelland, Courtney’s collaborator, rival and closest peer: in a band with her boyfriend, ugh. Fiona Apple, Liz Phair, good lord.

- Love’s voice, though diminished, seems to have avoided the fate of many former cocaine users (yes Whitney, I’m talking to you), and her melodies are still challenging (did you ever try covering a Hole song? They’re very hard to sing). Though her recent live performances include a fair amount of hoarseness and the occasional bum note, Love’s characteristic throaty sustain and growly decay are still present, and her tone is infinitely improved from its paper-thin incarnation on America’s Sweetheart; she no longer deserves the frequent comparisons to Marianne Faithful.

- It’s worth remembering that Britpop was originally intended as the UK’s two-fingers to grunge; it’s possible Love intends the same gesture