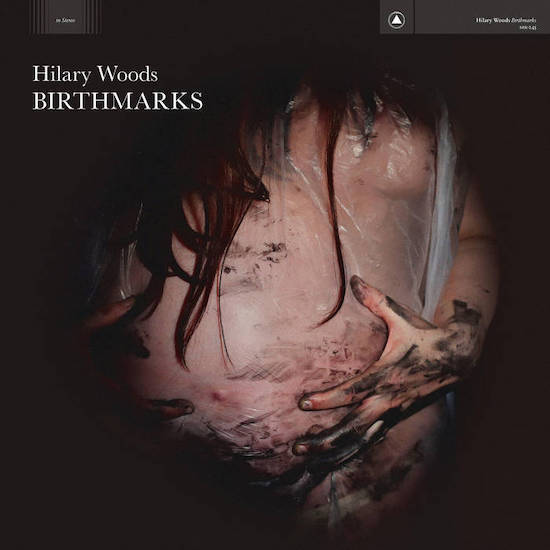

The drawings of Francis Bacon. The films of French polymath Chris Marker. The experiential collapse of community, and the power of the lone human voice. These are just a few of the things that have imprinted themselves upon the rich tableaux that is Hilary Woods’ second album. Marking her return to Sacred Bones, Birthmarks is a deft exploration of selfhood and becoming, and a marked step-up from an artist whose trajectory has promised a release that could stop you in your tracks.

Having scoured interior worlds to tackle disquiet with real restraint on her 2018 debut album, Colt, Woods intently ups the ante on Birthmarks. Written over two years, and recorded whilst heavily pregnant between Galway and Oslo, the album is a dense and deceptively weighty departure from the skeletal bedroom narratives of trauma and recovery of Colt. Working in tandem with Norwegian experimental noise producer and filmmaker Lasse Marhaug, Woods’ second feature-length siren song is, though largely muted, resounding.

The first few seconds of lead single ‘Tongues of Wild Boar’ confirms that things have changed. With wisps of static melding with thuds of sub-bass dread, Woods’ opening portent is tempered with all the calm, unforgiving majesty of Abyss-era Chelsea Wolfe. And while ‘The Mouth’ is a first-rate folkloric tale, coloured with tortured slithers of brass evoking side scenes on Carla Bley’s Escalator on the Hill, another peak, ‘Through The Dark, Love’ hits home with all the inward-peering fixation of Azure Ray striving to make themselves heard above Dean Hurley’s more scorched sound design on Twin Peaks: The Return.

Just as the sepulchral presence of cello is ever-present here (most notably on ‘Orange Tree’, a highlight that conjures Enya waxing dark with Earth circa Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light) a carefully-woven thicket of ambience proves a constant throughout. Across eight tracks, rustles of unplayed stringed instruments marry with field recordings; meanwhile, hushed vocals and the breath sit well with sable saxophone, electronics and heavy noise processing. Paired with Woods’ quietly defiant refrains, it makes for a thrilling and scopic round trip from its source to the still sea of closer ‘There is No Moon’.

While it’s tricky to resist viewing Birthmarks via the lens of worldly peril that most of us wake up to each day now, as one enters further into the fold of Woods’ soundworlds – those of exploring hidden gestational growth and the birthing of the Self – so much more character and colour other than vantablack claims dominion. By centering in on inner – very personal – transmutation in the face of broader anxiety, all while sketching such a fecund portrait of the innate synonymy of nature, death and birth, Woods offers up an opportunity to step back, take stock and see where we can all envisage new beginnings despite it all.