Few nations have experienced as much turmoil as Haiti, yet fewer nations have as rich and diverse an assemblage of cultures in their heritage. The Creole language and voodoo (henceforth to be written as the more correct vodou) practices are all mixes of West African, European and Taino (the now extinct pre-colonial Haitian natives) traditions, woven into a new, distinctly Haitian culture all its own. Also salient to this particular set of music – and modern Haiti in general – are the oppressive dictatorships that blighted the latter half of the twentieth century. ‘Papa Doc’ (François Duvalier’s nickname) was in power from 1957 until his death in 1971, at which point his son (the ingeniously dubbed ‘Baby Doc’) took over until fleeing amid widespread angry protest in 1986, leaving the nation in tatters.

This compilation of Haitian music recorded between 1960 and 1978 plays out as a slyly parallel history of the era, filled with joy, rampant expression and explosive creativity – the everyday struggle of extreme poverty and violent oppression remain largely absent from the songs themselves, but hover ghostlike out of earshot. Like many oppressive 20th century dictatorships, the rule of Papa Doc forcibly inspired celebratory music from its population as a means of propaganda; smiles forced at gunpoint. The lives of the artists on display here were, like those of all Haitians, somewhat under the spell of the Duvaliers. Some were jailed, while others were patronised, writing lyrics in praise of the regime and Tonton Macoutes (Papa Doc’s thuggish paramilitary named after a mythological Creole child snatcher). But it was all a smokescreen.

As detailed in the excellent liner notes for Haiti Direct, Papa Doc Duvalier was keen on hijacking the distinctly Haitian culture for his own purpose, and the emerging compas direct musical style around the end of the 1950s – which blended meringue rhythms from the neighbouring Dominican Republic with Haitian vodou jazz – fitted the bill perfectly. Resultantly, it was “swiftly claimed and held aloft as both an authentic and progressive example of Haitian culture.”

Though malevolent in its intent, the regime was most definitely correct to encourage compas direct and its related styles as beacons of Haitian culture. It’s filled with the fervent energy, beauty and mysticism that define the nation, and quite ironically, much of that powerful optimism

no doubt helped Haiti’s millions through decades of dictatorship, poverty and violence.

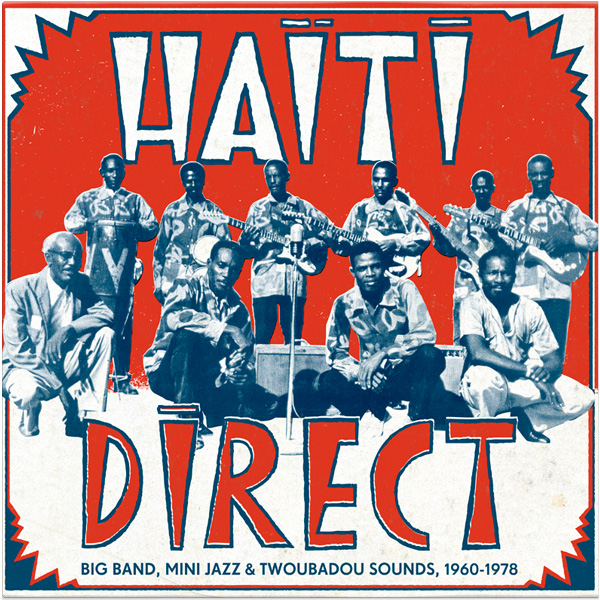

Compiled by Hugo Mendez of Sofrito, a tropical music-obsessed collective behind some excellent releases of their own, and released on Strut, the label behind some incredible recent compilations (including the seminal Next Stop…Soweto series of South African music), Haiti Direct is essential for more than the ‘global music’ heads alone. Considering Haiti’s unique culture, and the conditions under which the music was made, it details both a very human triumph, and the stunning recent musical history of a nation that’s often near invisible.

This compilation gives a pretty hefty overview of Haiti’s original music from the 60s and 70s, tracing a route from the big bands of the late-50s, through to stripped down and often guitar-centred ensembles and ultimately the return of larger groups embellished with horn sections in the late 70s – which in a broad sense sounds identical to the journey taken by European and American popular music during the same period with big band jazz, rock & roll and eventually funk and disco. However, the similarities with European and American pop pretty much end there. While the busy rhythms and Hispanic tropes arriving from Cuba via Dominican meringue lent Haitian musicians a blues-less base already far more complex and alien than other pop music of the time, there’s a certain chant at the core of this music that seems markedly Haitian. One track, ‘Gadé Moune Yo’ (‘where are the people?’), is a 1972 recording of an older more traditional street festival style called ‘râ râ’. In what is little more than percussion and call-and-response chanting, it’s impossible not to hear the music’s African roots, albeit refracted through generations of cross-cultural influence. Elsewhere, on the upbeat ‘Choc Vikings’ (from 1971 by Les Vikings, who clearly had a big thing for Vikings) the wailing sax of bandleader, Jean-Fritzner Delmont battles it out with stellar guitar fills and vocal chants atop a bed of accelerated hectic percussion and bass. As with all of Haiti Direct, the energized call-and-response of Les Vikings’ hypnotic phrases, despite its madly Latin setting, remain somehow more blatantly Afro than anything; more ceremonial and less married to Western classical forms than European-rooted new world music.

Haiti Direct perhaps unavoidably invites listeners to hear the music as a linear story of maturation, to compare the very basic Perez Prado-style mambo by Pierre Blain (‘Jouc Li Jou’) from 1960 with the almost laughably complex and bombastic epic ‘Ti Lu Lupe’. From 1978 and by Scorpio Universel, it’s replete with a hilariously tacky extended synth solo during its second half. The introduction of guitars, electric organs and later synths, offer some signposts throughout Haiti’s parallel pop history, but the progress, and ups and downs of Haitian music from this time is incredibly rich and dauntingly complicated.

Like the many dozens of compilations currently detailing the 20th century’s many thousands of unsung global subcultures, Haiti Direct aims to help fill in a gap in the history books. The difference here is quite how thoroughly unappreciated this music has been, and just how thoroughly appreciated it deserves to be. There are countless high points, memorable moments and addictive grooves on these two discs, and Haiti Direct is most certainly already a candidate for compilation of the year.