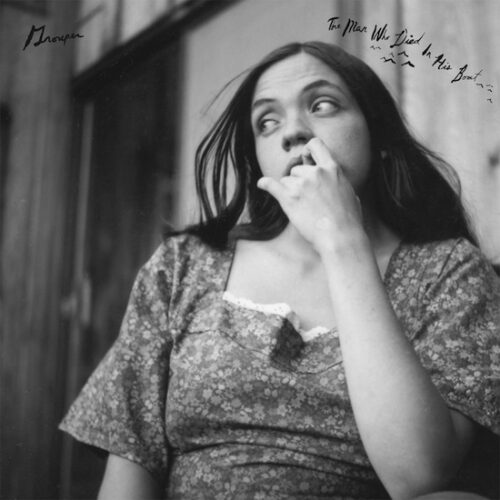

Strictly speaking, Grouper’s new album isn’t a new album. The Man Who Died in His Boat is actually a collection of unreleased material recorded at the same time as 2008’s Dragging a Dead Deer Up a Hill, Kranky’s reissue of which coincides with the new record’s release. So if you’re after something entirely new, you won’t find it here. That being said, these eleven new tracks of soft-focus oneiric pop are exquisite, the equal of anything on the first album. Like its complement, The Man Who Died in His Boat is located somewhere between fiction and reality – or, if you like, between waking and dreaming. Liz Harris herself penned the press release, an oblique autobiographical narrative:

"When I was a teenager the wreckage of a sailboat washed up on the shore of Agate Beach,” it reads. "The remains of the vessel weren’t removed for several days. I walked down with my father to peer inside the boat cabin. Maps, coffee cups and clothing were strewn around inside. I remember looking only briefly, wilted by the feeling that I was violating some remnant of this man’s presence by witnessing the evidence of its failure. Later I read a story about him in the paper. It was impossible to know what had happened. The boat had never crashed or capsized. He had simply slipped off somehow, and the boat, like a riderless horse, eventually

came back home."

The impalpable longing of that story permeates the album. It’s not folk music, though it

certainly contains elements of folk, notably in its sparsely plucked acoustic guitar and a

penchant for storytelling. The motifs of nature that dominated Dragging A

Dead Deer, where four track titles referenced water and two wind, are equally

central to The Man Who Died in His Boat. Waves lap at the edges of the title track as

Harris’ voice, layered like a palimpsest and awash in gossamer-light tape noise, plaintively

sings of the ancient enigma of the sea. These songs have a deliberately aged patina, but

unlike, say, phony Instagram filters, or the pops and crackles of Burial’s recent ‘Truant’, they feel eldritch rather than retro.

They’re devastatingly beautiful too, mostly the kind of dream-pop whose lineage can be

traced to the Cocteau Twins, filtered and scuzzed into a state of soft mulchy decay, with a

granular ambience at work that recalls Harris’ sometime collaborator (and Root Strata label boss) Jefre Cantu-Ledesma, or Yellow Swans in a meditative mood. A warm wind wafts about ‘Vital’, with field recordings, stripped-back guitar lines and wraithlike vocals making for a deeply personal evocation of nature that’s uncanny and tender. By contrast to the loops-and-effects overkill of her debut album Way Their Crept – though in much the same vein as Dragging a Dead Deer – the William Basinski tape decay textures, field recordings and filigree drones that shroud these tracks accent Harris’ compositions rather than obfuscating them. Lyrics are often indecipherable, lending Grouper’s voice the quality of a drone, a diaphanous murmur divorced from literal referents but charged with emotion. You hardly need to know what she’s actually saying in ‘Being Shadow’ to feel an ancient pain surface.

Poppier songs like ‘Cloud in Places’ belong to the world of the waking; here, Harris’ raw

mortification and instant regret at encroaching on a private space gnaw at your own

experience. Her voice glows with warmth and love in ‘Towers’, reverberating softly over a

languidly strummed guitar, offering merciful respite from all the melancholy. Other songs are

more impressionistic. While wind takes on a dense, low quality in ‘Difference (Voices)’, on

‘Vanishing Point’ it’s lighter, billowing through an empty space into which spare piano ebbs

and flows, all swathed in gauzy tape hiss. ‘STS’ is the album’s darkest moment, embodying

the sea’s deathly fearsomeness with a deep somnolent drone and murky filtered vocals.

Just as the poignancy of the image of a riderless boat filled with ownerless relics is born from

lack and mystery, so these compositions are haunting because Grouper gives them space to

breathe, filling that absence left by the unidentified lost man with her own hushed emotional

response. If you’re still unmoved by the time you reach the final song, well, you’re probably as

dead as he is.