Halloween, the year 2000. I am stood up to my knees in thick mud in the middle of Shepherd’s Bush Common on a cold, wet, autumn evening after taking a short cut from the tube to the Empire, where I’m supposed to be doing my first ever piece of paid music criticism, a live review of Grandaddy for the now-defunct Music365 website. Somehow, my desperate shortcut (I am running late, as usual) seems to have led me into what is the only deep bog within London Zone 2. As I pull my feet out of the oomska with an enormous squelch and look around at the close darkness of this tiny spot of rus in urbis (the Tube station has a giant photograph of a shepherd in a similar spot) the trees are silhouetted against the bright lights of the cars and shops of the Uxbridge Road. I laugh at the aptness of this muddy misadventure.

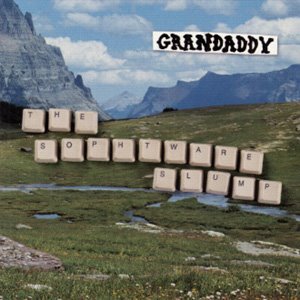

Because Grandaddy’s The Sophtware Slump, now reissued, remains one of the finest musical explorations in recent times of our insecurities over technology and the environment. And, West London mud aside, its elegant music and vivid lyricism made for an unromanticised evocation of the American pastoral. Of course, in the eleven years since its release, we’ve become all-too accustomed to Americans with beards and threads of plaid evoking and eulogising that countries’ vast open spaces, and humanity’s place within. But unlike Fleet Foxes and their ilk, Grandaddy never fell into the trap of assuming that such things could only be explored by backward-looking rootsy traditionals.

Grandaddy were always more wide eyed and futurist than that, just as were their peers: The Sophtware Slump was certainly a record that felt very post-Deserter’s Songs and The Soft Bulletin. But where Mercury Rev took a dark wander through the landscape of the Catskill Mountains, Grandaddy were the spaceship hoving into view over the treeline. And while the Flaming Lips dealt in quasi-spiritual cosmic Technicolor, Grandaddy seemed more grounded, frail and unsure at times, but at least certain the branches around weren’t about to turn into serpents.

Jason Lytle later told The Guardian that much of the album was written "in my boxer shorts, bent over keyboards with sweat dripping off my forehead, frustrated, hungover, and trying to call my coke dealer". This is hardly the typical picture of the American folk muso, sitting winsomely in his cabin. Instead, it speaks of a collision of discomfort, disorientation, uncertainty, decadence. I’ve long thought that the character of the robot Jed might actually be thought of Lytle himself, suffering "the shakes from the night before". Perhaps for that reason The Sophtware Slump has always unconsciously made me think of a Berlin-period David Bowie strung out in high viz gear trying to get on with the rest of the lumberjacks on a cold forestry plantation in Wyoming. But there are other similarities with the Thin White Duke, too – the ambient textures, the sense of a world trembling with the potential and fear of technology and futurism.

‘The Crystal Lake’, for instance, sees field recordings of water dancing with synths, like a burbling mountain stream of snowmelt and liquid mercury. It’s also one of the greatest American alt-pop songs of the past 20 years. ‘Hewlett’s Daughter’ and its talk of "the wrecks / Of ice shelves and glaciers" and "stolen guns" hints at a post-apocalyptic scene. It’s not hard to surmise that Hewlett relates to Packard, a computer that has, like the thirsty robot in ‘Jed The Humanoid’, become sentient. Indeed, throughout The Sophtware Slump (see also ‘Broken Household Appliance National Forest’) there’s a sense of the human, technological and unquantifiable sublime in nature colliding together with uncertain response. This is surely why Grandaddy’s vista of insecure vocals, artfully executed electronics, and deft multi-instrumentalism works so well, giving ‘Jed’s Other Poem (Beautiful Ground)’ or the utterly transcendent closer ‘So You’ll Aim Toward The Sky’ such fragile power.

It was perhaps this fragility that prevented Grandaddy from breaking through to the mainstream. Certainly, personal tensions that led to the band’s eventual demise didn’t help. Neither did the imminent obsession with all things scratchy, scrotty, and simple when The Strokes and their English counterparts The Libertines came along with their self-aware skiffle on the urban nocturnal. But The Sophtware Slump endures as a truly great American album. Listen to it as the saplings crack the pavement where "flowers reside with filthy rags", vines climb abandoned buildings, the green light fades from the last computer terminal, and the city returns to mud.