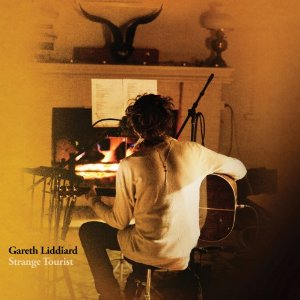

Middlebrow dullards love it when this kind of shit happens, when songwriters of a certain rackety ilk, renowned for an afflicted and corporeal take on rock modes unplug themselves. Tool down, all humble and that. Just them and an acoustic guitar. Mature. Grown up. There’s something about the supposed bravery of such an act that meets with their stern approval. Because, essentially, what these folks really get a chubby over is the notion of craft. Of emphasising some utterly irrelevant notion of song-writing aptitude, freed from the meddlesome bluster of the group environment. But despite the solipsistic purposefulness of the sleeve design, the debut LP from The Drones Gareth Liddiard is a deceptive subversion of rockist dogma.

I’ve always been somewhat fascinated by The Drones, or more precisely, how certain types of people react to them. I remember seeing them live for the first time in 2005, supporting Deerhoof and Alexander Tucker in Glasgow. The last thing the hipsters wanted was the caterwauling sturm-und-clank of a full on rock show. Thick post-Stooges morass, solo licks painted on with white light, opening bottles of Stella with a lighter, "nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nah nahs". It wasn’t like everyone hated it. It’s just that the post-internet fragmentation of schools and movements has not served genre well. Despite the deliciously morbid trajectory of their thematic concerns and the disorientatingly cathartic skronk of their music, to some folk they will always be yet another example of redundant guitar posturing.

Those very same folks are therefore highly unlikely to glean much from Strange Tourist. Billed by Liddiard himself as "The Drones, only there’s less of them", these are sprawling venom inflected dioramas existent in their own haunted ecology. The arresting title track, with its fizzing rough hewn picking and yearningly apocalyptic imagery, is perhaps the only song which could survive the electrified full band treatment without siphoning off a significant amount of its own earthen appeal. An escalating howl against the moon that takes in one man’s experiences with destitution, smack, war, arrest and Scientology, it’s perfectly ladled on by Liddiard’s snarling Ocka drawl and nicely encapsulates the narrative preoccupations of the record as a whole. These are screeds etched from a conflicted past and a decided lack of moral absolutes. From wartime collaborators through to home-grown radicals and wastrel fathers, dishonest lovers and sinister corruptors.

It’s in isolationism – both of Australian geography and Liddiard’s recording environment – that these characters are able to surface, their long dark nights of the soul feeding into the pores of song. The violent birth pangs of a nation are forever ripe for the fostering of macabre folklore and Liddiard has always done mythology, his compositions, like that of The Birthday Party and The Scientists shot through with that barely suppressed air of violent sarcasm that sits at a slight angle to the rest of the universe. Yet it’s to Canada via France that he turns to for the albums opening salvo, an existential rumination on the nature of the public’s adoration for Charles Blondin, the wire walker who crossed Niagra Falls in 1859. Written from the perspective of his faithful assistant, it’s an often ambiguous interpretation of the psychology of those who gawk at risk takers: "but I ain’t here because he’s tall, I’m only here to see him fall, and if I get on the wagon now it’ll only be to run him down." Just enough information is withheld yet it’s tenderly methodical and filled with enough pathos for it not to collapse under the weight of didacticism.

Such once removed, personalized microcosms of anger imbue Strange Tourist with a brusque politicisation. No easy answers. The shoulders to cry on are just as often bastards, the sociopath who got dealt a bad hand and never found his way home. In ‘The Collaborator’, things are pitched even more sinisterly. The lurking paranoia of the wartime populous attempting to unearth evidence of those who aided the invaders, accusations and defensive rebuttals crowed back and forth, carried along by Liddiard’s flinty, nasal declamations. Indeed, his is quite a voice. He sings with a half-spoken, often crowded cadence, elongating or truncating words and hinting at hidden meanings through sudden flights of possessed semi-wails. While the music remains crystalline and austere in its unhurried strums and cliff edge teetering, Liddiard’s voice is capable of a more satisfying versatility most readily in evidence on ‘You Sure Ain’t Mine Now’, during which he delivers the refrain in a canine falsetto.

The aforementioned sprawling nature of each track – most nudge the nine minute mark – isn’t always totally immersive. The cumbersome ‘Did She Scare All Your Friends Away’ serves as a signpost for the weary near the albums end yet it is followed, mercurially, by the magnificent ‘The Radicalisation of D’, a sixteen minute long, meticulously researched piece of empathetic engagement inspired by the life of David Hicks, an Australian inmate at Guantanamo. It’s a superbly engaging quarter of an hour, the grim horror of what is about to unfold humanized implicitly by Liddiard’s unhurried use of authentic Australian motifs (hills hoists, ging’s). It’s a piece of songwriting that genuinely attempts to understand why some people become susceptible to extremism. More uncompromisingly, it suggests that they may have a point. This record requires patience, demands concentration, but this climactic gesture more than justifies those efforts.