This is the fifth edition of Radical Traditional, my column exploring experimental, left-field and forward-thinking takes on traditional music from across the planet. It also marks the project’s first full trip around the sun, in which time it’s been pleasing to see that the kind of music it was established to cover continues to sprawl into new directions.

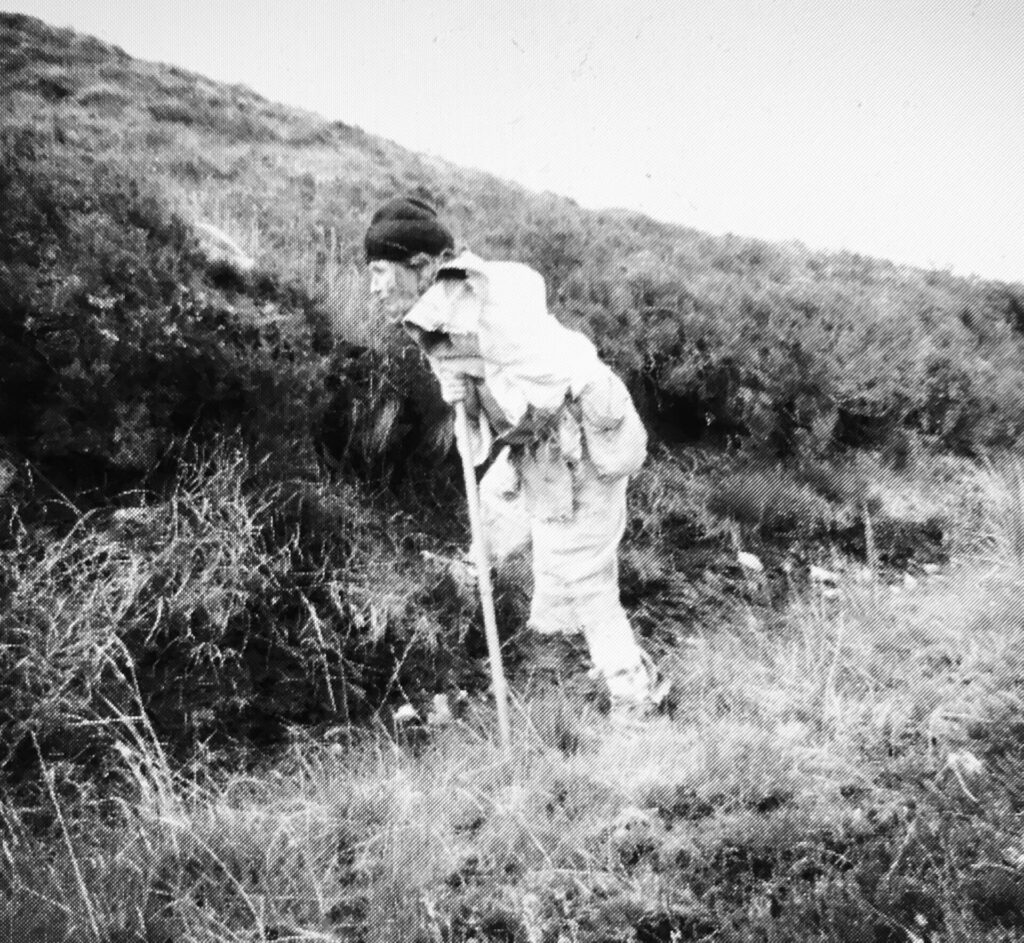

The anniversary also marks a change in the way the column’s being presented. As regular readers will know, Radical Traditional has usually begun with an introductory essay, based around interviews with people I regard as among the most important or interesting when it comes to the current drive to push folk culture into bold and progressive new places. This time around, I had decided to focus on morris dancing, and how, in my opinion, its common reputation as the embarrassing hobby of stuffy, regressive, real ale-swilling blokes, does a disservice to what is really something that’s deeply radical and transgressive. I charted a line from Cecil Sharp – for whom an encounter with the Headington Quarry Morris in 1899 was so revelatory that the roots of that generation’s so-called ‘folk revival’ can be traced back to that exact moment – through to my own Damascene encounters with the dance as a bright-eyed Quietus intern in the 2010s, and to the dancers continuing to push things further forwards today.

As that piece sprawled into a 3,000 word epic, however, we at tQ thought it would be better served as a standalone piece of its own. That was published yesterday, and you can read it in full here.

That gives us a bit more space here to delve solely into a batch of releases that for my money are as fantastical, as imaginative, and as forward-thinking as any others we’ve yet covered in this column, and deserve your full attention. So enthralling were some of them, that I’ve also ended up devoting them more words than usual. Without further ado, then, here are 10 of my current favourites.

Junior BrotherThe EndStrap Originals

The End begins with a shrill, looping whistle, then a rattling clip-clop of wooden percussion and a queasy accordion, then a primal thud of bodhran drum, then a barrage of plummeting drones. The sounds circle each other like water round a plughole, before suddenly lurching all at once in a downward plunge. Then, a stretch of eerie quiet, a different drum beat that’s rapid like a terrified heartbeat buried in the distance, before another plunge – even deeper down beneath. “Lost, in the grinder / I am lost, in the grinder,” sings Junior Brother. “Now the world grinds round and round, down and down and round and round forever.” These words are no invention, but taken from the direct account of a man who found himself lost in a Fairy Fort.

Fairy Forts are ring-shaped banks of earth found throughout the Irish countryside – many of them the remains of stone circles or prehistoric dwellings – said to be defended from destruction by ancient supernatural entities known as The Good Folk. Step inside the ring, and you’ll find yourself bedazzled and disorientated. At twilight, the eagle-eared might hear an otherworldly parallel version of Irish music floating its way toward them – this informed the sonic palette of The End, where traditional Irish instrumentation (bodhran, accordion, tin whistle, mandolin, uileann pipes and more) is pushed into strange and eerie new climes. The record consists of labyrinthine songs that stop and start, speed up and slow down, spin and twist and loop over themselves and fray at the edges. Keary’s voice shapeshifts along with them with them, sometimes a cracked soul, sometimes a deranged howl, sometimes a bedazzling babble.

If Keary’s aim was to recreate the feeling of getting lost in a Fairy Fort, the record is a success, but what’s even more interesting is the way that he uses that central theme as a lens through which to view other rabbit holes – the protagonist of ‘Small Violence’, his brain warped by toxic online conspiracy theories, is here presented as a gibbering mess, plagued by similar hallucinations to those that might be imposed on him by supernatural entities. The time-warp of the pandemic, too, is present throughout. The semi-manic ‘Week End’ was inspired by the way the boundaries between days blend into an ungraspable soup under quarantine. On ‘Plague Medal’ the real account of a man whose claims to have shot the winning puck in the fairies’ invisible hurling match (naturally met with disinterest when relaying his tale), is related to the strange sensation of looking back, post-lockdown, at a time that felt only half-real, with a strange sense of achievement but nothing tangible to show for it.

Then, in final meta twist, there is the grand sweep of closer ‘New Road’, where The End itself is revealed to have been a Fairy Fort of its own all along. The record was written, Keary notes, during the longest period he’d spent since childhood in his family home in County Kerry, where he had allowed the energy of his rural surroundings and local oral histories to seep their way into his work like never before. A day before he returned to Dublin, he was brought crashing back to reality plans were announced to build a motorway directly through that exact area, to pave over all those supernatural patches of land and to bulldoze his parents’ home. At the record’s close, Keary’s voice fades away into a sprawl of ambient electronics and mournful Uillean pipes – a lament for the unseen energies that are buried in the name of progress.

Jennifer ReidThe Ballad Of The GatekeeperWeaver’s Friend

Jennifer Reid became an expert in 19th Century English folksong when she volunteered at the medieval Chetham’s Library in Manchester, where she encountered a collection of broadsides and started cataloguing them by place. Seeing the names of the same northern towns and villages that she knew herself was a bolt of inspiration – that these were real places, populated by real people, their wants and needs and sorrows and joys so similar to her own. You’ve heard it all before, I assume – new musicians ‘breathing life’ into old songs is by now a cliche. What Reid recognises perhaps more than anyone else in her field, however, is that there’s really no need to ‘breathe life’, that old songs are still brimming and bubbling with life of their own. The trick instead is to channel that energy, to allow it to possess you, to mingle with your own vitality and expel it into the present.

And boy, does The Ballad Of The Gatekeeper feel alive. Reid has an intense charisma, and she uses accompaniment sparingly. It is occasionally theatrical, but at no point does it feel imitative or like a recreation. Thematic parallels between past and present are easy to locate. Consider the resonance of the titular characters on ‘Poor Little Factory Girls’ that draw parallels between 19th century Lancashire weavers and modern day South Asian garment workers (among whom Reid has spent time), for instance. Though steeped in the history and dialects of northern England, this is a record of universal resonance.

This is only one half of the record, however, which also features a number of self-penned compositions that speak to directly to the wider aims of the project, which Reid has stated as being “to give voice to underrepresented groups in the folk scene today and to highlight events we’re all going through.” ‘When The Rivers Rise, So Must We’ confronts climate change over eerie layered harmonies, while ‘In The Garden Of Change’ challenges a society “stuck in a binary”, their wrongheaded assertion that “nothing ever changed before here.” Whether in the constant communication between us and our ancestors, or gender identity, this is a record that argues boldly for the beauty of fluidity.

The WormPantildePRAH

The Worm is a character created by Cornwall performance artist Amy Lawrence, one they imagine travelling into a parallel Celtic landscape. The project’s primary expression is onstage, where, in the artist’s words, they embrace, in their words, “music, costume, clowning and spoken word recitals inspired by opera and dance from the early 20th century”. Presented purely on record as Pantilde, however, stripped of those multi-disciplinary bells and whistles, it’s no less engaging. After an enchanting opener, ‘Through Greenness’ – a recorder melody set to the sound of a babbling brook that’s akin to seeing a colourful alien flower bloom amidst green and brown undergrowth – comes ‘Portal’. “When you grow up, you will go through some kind of portal, made of birds,” relay eerie and detached vocals to an abstracted but organic backing of drones and twangs. On the other side of the portal comes ‘Grass Grows pt.1’, a naïve melody that lilts back and forth. “Grass grows, grass grows / On my toes, on my toes,” comes a simple refrain, as if a riddle mumbled by a child only to themselves. Therein lies the record’s central brilliance – not to immediately overwhelm with lore, but to provide a succession of strange little characters from whom little snippets about their wider world can be gleamed.

On the title track we find the nomadic owner of the titular Pantilde – a donkey – travelling from one community to another offering to fix pots and pans (kitchen equipment also the source of the song’s wonky percussion) in exchange for food and clothing. ‘Heva’s Village’ is a sorrowful aria from the perspective of a woman awaking on a freezing cold morning on her straw bed in a self-built thatched house. Later comes ‘Grass Grows pt. 2’, the naivety of the first section replaced with a newfound pensiveness. “Grass does not grow on you, you are not made of stone,” comes an altered refrain, innocence now muddled with age. Gradually, though, the record builds in its scope, until on ‘Journey’ it reaches a fantastical creation myth. The song is delivered from the perspective of a foetus in the body of a mother “living on a hill with grass and flowers,” and yet who also simultaneously walks the earth as a grown being elsewhere. “My grandmother was The Worm Moon, who gave birth 13 billion years ago and said: ‘It is prophesised that you will die, falling and bouncing on the blade of a windmill.’ I don’t know what a windmill is.” After an opaque ambient interlude, (its title ‘Falling And Bouncing’ implying that it might be that process of death made into sound), comes ‘The Tower Of The Eclipses’, and the perspective of The Worm Moon herself, her own mother the moon, her father the sun, whose home (the Tower itself) is somehow situated on a beach. Wrapped in so many enigmas, contradictions and riddles, the search for concrete meaning is pointless. Rather, this playful, strange and wondrous record should be the listener’s to make of what they will.

Poor CreatureAll Smiles TonightRiver Lea

Poor Creature began as the lockdown project of Landless’ Ruth Clinton and Lankum’s Cormac MacDiarmada, arranging songs together with no larger aim. Early interactions with the world outside were via online livestreams, while their first proper show, with Lankum’s live drummer John Dermody now in tow, was entirely improvised – part of a last-minute fundraising effort for a greyhound’s hip replacement. This sense of allowing things to take shape playfully and organically extends to the first track on their debut album All Smiles Tonight, where some elements swirl and float around the listener, disparate at first but slowly coalescing, like atoms turning into molecules, and eventually into structures that grow bigger and bigger and bigger. Others, meanwhile, have an anchoring quality, holding the listener in place while a universe of sound takes place around their ears. Take opener, ‘Adieu Lovely Eiereann’, for instance, where Clinton’s vocals are centred, unmoved by the rising droning electronics and clattering percussion. Even when a staggering blast of organ joins the fray, she stands firm – the song developing a richly psychedelic energy thanks to the contrast.

There is another such burst of organ on ‘An Draighneán Donn’, coming five minutes into a drift of disembodied, echoing voices. Here it is more staggering still, warping in and out of tune to intense emotional effect. Similarly, the ghost story ‘Willie O’ is a transfixing 10-minute epic that in its closing stages recalls the sound of an air raid siren sounding from beneath an ocean. ‘Hick’s Farewell’ is a slab of gothic gloom. Despite the drone and grandeur, however, there’s as much light as there is dark on All Smiles Tonight, and an appealing roughness around the edges throughout thanks to a palette that includes a vintage organetta, theremin, and novelty Otomatone synthesiser. ‘The Whole Town Knows’ rides a spry, twanging rhythm. ‘Bury Me Not’ sails gentler waves, buffeted by sweetly off-kilter synthesiser melodies. ‘Loreen’, which sees MacDiarmada on solo vocals, is just straight-up beautiful.

LunatraktorsQuilting Points: Invitations And Open Calls 2019–2025Broken Folk

Lunatraktors, the duo of Clair Le C and Carli Jefferson, have been purveying what they call ‘Broken Folk’ for some years now, with Quilting Points collating a number of different recordings – salvaged from a corrupted hard drive and stitched back together again – from the numerous different commissions, open calls and collaborations they’ve taken part in over the last seven years. As a collection, it sees their focus skipping across history. They travel to the late Bronze Age on ‘Hoard’, where they provide a weird and organic soundscape to the Havering Hoard, to ancient Rome on ‘Laurentalia’, with the incorporation of the ancient pagan chant the Carmen Arval into a dark and ritualistic invocation to a bronze statue depicting a household god; to the Anglo-Saxons, with a commemoration of England’s first female Saint, Eanswythe ,and the forensic study of her remains; to the industrial revolution, via an improvisational duet with clog dancing for the artist Brigid McCleer’s piece Collateral, commemorating the victims of textile factory fires.

It veers, too, between varying levels of abstraction. While there are points Lunatraktor’s experiments recall pure sound art – an exploration of sonic resonance in the back stairwells of Zurich’s Kunsthalle, for instance – there are also plenty of straightforward songs both original and traditional, running the gamut from the comedic and camp (they have roots in cabaret) to the deeply serious. There is beautiful reimagining of George Ware’s ‘The Boy In The Gallery’ to celebrate the history of gender diversity in pantomime and Music Hall, a tender lament for the gaps in the folk archive where LGBTQ+ narratives have been omitted on ‘Now The Time’ (queerness is also at the centre of the duo’s practise), a dark, droning rendition of the Samhain song ‘St. Martin’s Land’, and the enjoyably wonky ‘Wassail’ that was inspired by their leading a public ritual at Compton Verney. It all adds up to a record that is a celebration of creativity itself, how delving into the past allows us to prod and probe at the nooks and crannies of the present with renewed incisiveness.

Brìghde Chaimbeul Sunwisetak:til

By now, the brilliance of Scottish small pipes player Brìghde Chaumbeul is well established, but the way she’s continuing to continue to push the instrument forwards on her third solo LP Sunwise is still worth flagging. Opener ‘Dùsgadh/Waking’ finds Chaimbeul deploying her pipes with more subtlety than in the past, their drone a gentle lure rather than the big tidal wave of intensity that marked a lot of her previous work. ‘A’Chailleach’, that follows, shows the growing influence of experimental, minimalist and avant-garde composition – the pipes reduced down to a hypnotic, gradually developing loop.

On ‘She Went Astray’, Chaimbeul’s rapid singing is backed by simple intermittent blasts, while on ‘Duan’ the pipes are gently twisted and warped by moody electronics, before fading to the sound of a crackling fire and a recording of Chaimbeul’s father Aonghas Phàdraig Chaimbeul reciting a rhyme related to New Year’s Night, traditionally used to precede the oidhche chaillain – a disorderly procession three times sunwise around each house in the village. Her brother Eòsaph appears too on a quick and bracing closer, ‘The Wine And The Stones Are Cheese’, where they trade canntaireachd vocals (a means of vocalising bagpipe music, often used when teaching the instrument) in a traditional song to mark the longest night of the year. Released just after the summer solstice a few weeks ago, the point the days start shortening, the record “follows the embrace of wintertime, the closing in of darkness, the cold, the pull to turn inward,” as she puts it. Like a crackling fire glowing in the dark, this warm and inviting record is her finest yet.

Various ArtistsNew TraditionsWild Raver

Chaimbeul appears again (and also contributes as a translator) on this fascinating collection of recordings from rising Scottish traditional artists, all of whom have taken wildly divergent approaches. Drew Wright, under his Hoch Ma Toch alias, opens with ‘The Waters Of Kylesku’, a song that maps the journeys of travelling communities in the summer. Inspired by a beautifully sparse 1955 recording of the traveller Essie Stewart, Wright’s version – the backing crafted entirely from layers of overdubbed vocalisations, clicks and whistles – draws out a new dreamy smoothness. Norman Willmore, meanwhile, takes another archival piece – North Uist native Kate MacCormick, recorded in 1956 – and manipulates and stretches it out into psychedelic ambient jazz. Chaimbeul’s brief and brisk composition ‘Naidheachd Mu Easgann Agus Òran’ is an original, though inspired again by an old recording, this time concerning a woman who was composing beside a lock, only for an eel to pop up and finish it for her. Harry Górski-Brown’s ‘Tha Sneachd Air Druim Uachdair’ – the tale of a man who shot the creditor who confiscated his wife’s kettle when she couldn’t afford the rent – is a standout, pipes electronically treated to the point they’re frayed and sputtering, vocals warped into the uncanny valley.

Then, ‘Oidhche na’ mo chadal dhomh’ by mysterious “celtic mongrels” Mother’s Favourite Tongue pushes things even further; their version of Neil McKinnon’s poem lamenting the English oppression of Scottish language and culture is utterly brilliant. Pipes groan into life, then settle into a muddy drone. Two vocalists, their stark voices pushed to the front of the mix, trade lines as the drone grows darker and stranger by the second until it all starts to buckle under its own weight, plunging quickly down into harsh static and then back up again, the pipe recordings briefly reversed back on themselves, crunching percussion stopping and starting. It is essential listening. Rather than one-up this masterpiece, closer Isa Gordon’s version of ‘The Parting Glass’ wisely undercuts it, transforming this oft-repeated ode to the departed into a charming psychedelic drift.

Linda Buckley, The Maxwell Quartet, Brìghde Chaimbeul Thar Farraige (Over Sea)

Yet another mention for Chaimbeul in this quarter’s column comes via her contribution to Thar Farraige (Over Sea), a work by the Irish composer Linda Buckley that weaves together folk music (via Chaimbeul’s pipes) with chamber music (via The Maxwell Quartet) along with deftly applied electronics. Originally commissioned by Chamber Music Scotland and performed live across Britain, Ireland and beyond over the last year or so, it follows a guiding theme of migration and connection to place that are integral to much of Celtic traditional song. This is done both subtly – the delicate interweaving of melodic lines drawn from Irish keening and Gaelic psalm singing – and directly, with the deployment of a scratchy phone recording of Buckley’s mother reading ‘The Moon Behind The Hill’, a poem about yearning for one’s home. The reading was recorded during lockdown, when Buckley was stranded from her family in Scotland, and was salvaged again when her mother died, early into Thar Farraige’s creation. It lends the work a personal edge, the grief of seeing a person depart for foreign soil intermingling with that of seeing them depart for the hereafter. (I also interviewed Buckley about the project earlier this year, which you can find here.)

Yui OnoderaKiso Three RiversField

In Central Japan three rivers, the Kiso, the Ibi and the Nagara, each flow alongside each other, sometimes joining together and sometimes separating again. This natural phenomenon is both beautiful and destructive – their intersections creating plains where even minimal rainfall can lead to severe flooding. In the late 19th century, with those floods threatening serious damage on nearby Nagoya, the Japanese authorities enlisted the Dutch engineer Johannes de Rijke to help separate them, an ambitious project not to be completed until 1912, and one that provides the foundational concept for a new work by Tokyo composer and sound artist Yui Onadera. It’s also the third in a trilogy commissioned by the label Field Records on the wider theme of Dutch hydraulic engineers (known as watermannen), who were enlisted amid the Meiji era’s rapid modernisation. This is a tale of multiple intersections – between man and nature, between Dutch and Japanese cultures, and between the three rivers themselves – is reflected in Onadera’s work, where instrumentation both traditional – the shō, a woodwind instrument that dates back to the 700s – and modern – artist Teppei Saito’s slit Hamon drum – intermingle with sparse ambient electronics, and field recordings from the rivers themselves.

Ancient HostilitySing As Loud As You CanSelf-Released

Ancient Hostility is a project consisting of members of anarcho folk-punk outfit All In Vain, and black metal band Dawn Ray’d – both fixtures in the Liverpool underground – whose debut album Sing As Loud As You Can is a direct assault of group singing in the vein of Swan Arcade or The Young Tradition, linked together by scratchy drones of violin and concertina. None of the songs here are traditional. All, save for a cover of Bob Davenport’s searing anti-authoritarian ‘Police Patrol’, are originals, and carry similarly direct political messages that respond directly to the present. ‘Immigration Van’ lambasts “the cruelty of snatching someone away,” while ‘Hammer’ provides a rousing call for class solidarity, advocating for direct action in the face of rising fascism and growing government tyranny. The method of delivery, however, a bold and stark style of political singing that has been practised for generations, finds resounding echoes in those who’ve done the same across centuries past. I have written many times about how songs from deep in the past can help us make sense of what’s around us today, but here is proof that it’s also a two-way street.