Practically speaking, silence doesn’t exist. It is constantly being broken, negated by the inconsiderate movement of things. And even if it did exist, you’d probably hate it. It would, in a sense, be horribly loud. Or maybe I’m projecting, thinking about the time I’ve spent in quiet, isolated spaces, and how the hairs on my neck would stand up, some part of my lizard brain at full attention, my ears scanning for a sound – any sound – to latch onto. Anything to fix myself into the space around me, feeling adrift, uneasy.

Félicia Atkinson is a great breaker of silence, even as her pieces toy with the idea of it, and the tensions wrapped up in it. Atkinson makes quiet – sometimes exceedingly quiet – music (though it has been called other things like sound poetry or even ASMR). To varying degrees, she has spent much of her career exploring quietude, the various shades of it. In many ways, it is her palette. But it would be foolish and certainly reductive to describe her music as “ambient”. It isn’t for airports. It doesn’t drift away, into the background, a canvas for the completion of crossword puzzles.

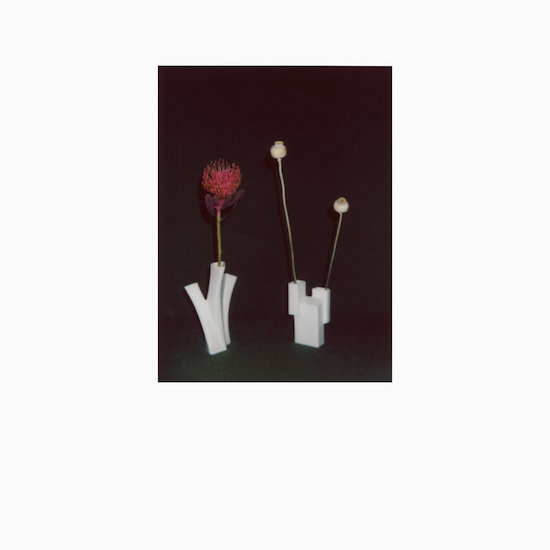

Though routinely gorgeous, her work is rarely relaxing, rarely comfortable. Atkinson actively situates her compositions in the intimate, unruly liminal space between comfort and discomfort, quiet and disquiet. This remains true of her new record, the beguiling The Flower And The Vessel, a work made not “while” pregnant, she asserts, but with pregnancy. A work made in part, she says, to reassert her connection to the world.

Atkinson’s stated need to reaffirm that connection is surprising, given how rooted in the environment – however surreally – her prolific body of work tends to be. While I suppose The Flower And The Vessel is the "proper" follow up to her magical 2017 LP Hand In Hand, last year she released an album-length cassette EP, Coyotes, on Atlanta’s Geographic North; a collaborative LP with Jefre Cantu-Ledesma, Limpid As The Solitudes, on her own Shelter Press; and the Félicia & Christina collaborative cassette EP with Christina Vantzou on Commend Here. Crucially, despite this slew of releases, the sheer level of quality has yet to flag.

The first two tracks of The Flower And The Vessel set the tone for the album. The first, ‘L’Après-Midi’, consists entirely of Atkinson’s too-close whispers-like-secrets and the sounds of the room. Her lyrics throughout the record always require intense concentration to decipher, are sometimes obfuscated, and frequently appropriated from other sources, contributing to a sense of unreality that permeates the LP. The second, much longer composition, ‘Moderato Cantabile’, pairs high-pitched, ethereal tones with a spare keyboard melody. It develops slowly, patiently, the tones settling around the piano like a mist, before a series of field recordings emerge, a bell or a chime or a glass, maybe a cough, the clatter of something, hard to place animal bleats.

Atkinson is a masterful, creative collector of such sounds, and she deploys them judiciously to great effect in her work. The Flower And The Vessel is no exception. As she says in Sam Campbell’s short film Sound Fields: Adventures In Contemporary Field Recording, “I like the fact that field recordings put you in the reality. It’s not pure artifact. All of a sudden, it’s the materiality of the world.” And indeed, this is often the role her field recordings play. They are a mooring line that keeps the album from spiraling off and out into completely alien territory.

Loyal readers of this publication may take a particular interest in The Flower And The Vessel‘s final track, ‘Des Pierres’, a drone epic featuring Sunn O)))’s Stephen O’Malley on both guitar and production. It’s a rich, sumptuous composition that finds O’Malley settling into and complimenting Atkinson’s peculiar aesthetic. Her vocals and organ intertwine with O’Malley’s signature guitar work over nearly nineteen serene minutes, as she leads him on a tour of the insular world she’s created but opened wide for all of us to experience.

Listening to The Flower And The Vessel, I’m reminded of my excursions into the deeply quiet, of the relief of long cicada drones or lone bird calls, of how sound is often a lifeline in an unfamiliar space. Those sounds resonated around my brain’s memory centres, turning unfamiliarity into something else. Something – if not exactly familiar – that I could connect with, nonetheless. Those things that broke the near-silence were impossible to ignore. The noise they made lingered long after they were gone. In this way, Félicia Atkinson makes loud – sometimes exceedingly loud – music.