In 1936, Esquire magazine published an essay by F Scott Fitzgerald, who was approaching 40 (and who would be dead a little more than four years later). ‘The Crack-Up’ reported Fitzgerald’s struggles with fame, relationships and the passing of time. The ruthless resolution he came to, to preserve his life and sanity, was to dehumanise the writer, to be a working shell devoted to the written word and with no emotional ties to any other person.

It doesn’t take a lot to uncover much of Robin Pecknold’s own narrative in Fitzgerald’s essay, but the Fleet Foxes’ leader came to a different conclusion. His time away from the spotlight since 2011’s Helplessness Blues and his seclusion as a student at Columbia University seems to have reinforced his belief that no man is an island, that human interaction is the greatest force of all.

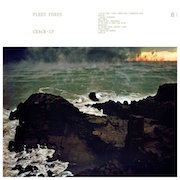

"Sometimes, though, the cracked plate has to be retained in the pantry, has to be kept in service as a household necessity. It can never again be warmed on the stove nor shuffled with the other plates in the dishpan; it will not be brought out for company, but it will do to hold crackers late at night or to go into the icebox under leftovers…" Fitzgerald wrote. And if some china has broken, Crack-Up is Fleet Foxes’ kintsugi, the Japanese philosophy of repairing pottery with precious material, turning the damage into an important part of the object rather than making it something to hide.

The first crevice to fill with gold was that between Pecknold and his longtime friend and bandmate Skyler Skjelset (who co-produced the album – the first time of Pecknold has given up complete creative control). This relationship is mended in the lines of ‘Third of May/Ōdaigahara’, where an analysis of a human connection overlaps with images from a Goya painting.

It’s not an isolated case: the whole album is a cabinet of curiosities to discover and decipher. Greek and Roman mythology sit alongside Ethiopian music (Mulatu Astatke’s ‘Tezeta’ is sampled in ‘On Another Ocean’), self-references (a high-school choir singing ‘White Winter Hymnal’ peeks through at the end of ‘Thumbprint Scars’) and Old English epic poetry.

And the sonic unity attests to the newly healed cracks between the five band members. Where once there were furious guitar strummings and bonfire-ready polyphonic singalongs, now there are complex compositions where tones and colours add layers of meaning. The Fleet Foxes’ established folk sound meets jazz basslines and vocals that let a clearer but darker sense of self emerge. It gives you the same sense of pitch black and bright flashes you experience, after you’ve hit rock bottom of the ocean, when you push back up to the surface, towards the light, to breathe again.