When an album is re-issued you have to ask the question “Why?”. Normally the answer is for the money. It feels like 90% of re-issues aren’t warranted or needed. You just need to look at the Record Store Day list each year to have this answer confirmed. However, there is a time when a re-issue feels necessary, and this is where Evan Parker’s 1978 album Monoceros fits in.

Monoceros is being released on Treader Records. The label was started by Spring Heel Jack, AKA Ashley Wales and John Coxon, in the early 2000s. Is has become a home for free jazz, experimental and avant-garde pop releases. Initially the label only put out limited runs of CDs. Each featured a one colour card case with a different animal embossed in gold. The music was just as striking featuring new compositions from Parker, Mark Sanders, John Tchicai, J Spaceman, Matthew Shipp, Wadada Leo Smith, and Alexis Taylor. After a three-year hiatus Wales and Coxon have now moved from CD to vinyl. These first records were a mixture of Treader reissues, new compositions, and a Spring Heel Jack album and EP released on the label for the first time.

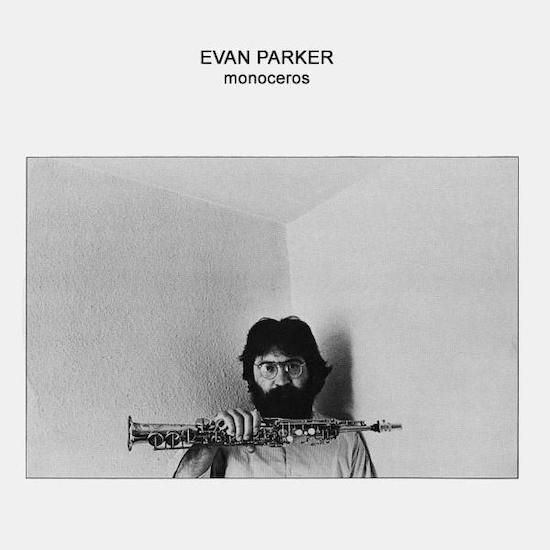

While I love talking about Treader, this isn’t really why we are here. We’re here for Parker and this ground-breaking masterpiece. Monoceros’ title refers to a one-horned legendary animal. The back cover of the album seen Parker playfully placing his soprano saxophone being his head, so it pokes out on top. The opening track, ‘Monoceros 1’, is a twenty-two-minute hypnotic thing of beauty. The playing has a fierce intensity to it. The way Parker intertwines his saxophone is just mesmerising. It’s as if the instrument has come alive and all Parker can do is hold on and remember to blow. However, there are times when Parker is very much in control and it feels like he is playing for all he’s worth. His triple-tongued technique sounds as unconventional now, but in 1979 it must have sounded other worldly. In your mind you can almost see the veins sticking out on Parker’s lips as he applies more pressure to the reed and just blows. His overtone control is also on full display throughout Monoceros. This technique was picked up from exposure to folk music in Africa and the Middle East. If this is all that Parker had recorded, Monoceros would still have been a seminal release. But it wasn’t. There are another three songs on the album’s second side. ‘Monoceros 2, 3 and 4’ are music shorter. The longest being nine minutes, but they possess the same levels of intensity and inventiveness that made ‘Monoceros 1’ such a joy.

One of the pleasures of Monoceros is how it still sounds challenging. Even after over forty years. This might be down to how it was recorded. Direct-to-disc. This means that everything Parker played, warts and all, would be included on the final album. At the time of releases this was the closest Parker could get to playing live in a club in a studio. The directness comes across in the recordings. ‘Monoceros 4’ is the shortest track on the album, but throughout its 4:08 duration it feels like Parker is playing live just for you. He soars, glides and plummets as hard as ‘Monoceros 1’ but you feel he has his eyes on you all the time. As you squirm, his playing is harsher; as you grin, he drops in a few playful motifs before continuing his overtone control – not just of his saxophone but of you, too.

Since the album was originally released Parker has released, and played on, hundreds of albums, thus cementing himself as one of finest UK jazz musicians. In the early 2000s he found a new legion of followers through his work with Jason Pierce and Spiritualized. After listening to Monoceros it feels like a proto-Treader album. The music is abstract but warming. This is the first time Monoceros has been re-issued since 2004 and the first time on vinyl. This doesn’t feel like a needless re-issue. It’s more like a homecoming.