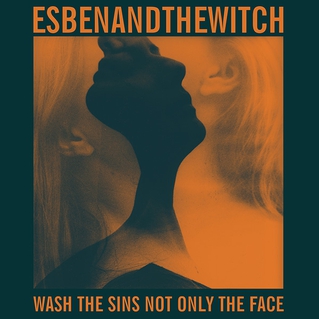

Quietly working away at a curious intersection somewhere between industrial shoegaze and techno pop, Esben & The Witch found themselves, in the space of a few short months at the tail end of 2010, signed by Matador Records and named on the BBC Sound of 2011 long list (their name incongruous alongside the likes of Jessie J and The Vaccines). Looking back, it’s easy to couple the rush and excitement of that period for the band with the criss-cross of directions, multiple flows of coded messages and emotive pivots that raged through debut album Violet Cries. Not so much the cliché ‘you’ve your whole life to write your first album,’ Esben And The Witch’s first outing sounded as though it had burst from them, the uncontainable energy of a pyroclastic flow. Even though notable steps forward have been made on Wash The Sins Not Only The Face, the shapes and configurations left by the ash of that blast still remain.

The most obvious progression is in the band’s move to cleanse their palette of some of the sonic impurities that made the textures of their debut so dense. Only on ‘Despair’ do they reach those previous levels of claustrophobic, elements-muscling-against-each-other chaos. Instead, tracks like ‘Slow Wave’ and ‘Shimmer’ are more considered and tactile. It was a direction that, really, they had to take: they couldn’t have gone much bigger than before without becoming overbearing; and by taking a step back they’ve still retained this tense, turbulent environment.

Notable, too, is how a few of these songs contain something of a more orthodox structure, with sections approaching choruses appearing on the likes of pre-release track ‘Deathwaltz’ and the dead-of-night timbral march of ‘When That Head Splits’. One criticism to be made of their last record was the relative disjointedness of it, even within its all-encompassing sound. Greater focus has been placed on structure this time round, though it’s not always immediate. The brooding run of ‘Slow Wave’, ‘When That Head Splits’ and ‘Shimmering’ in the album’s opening half hints tantalisingly at something grander to come later on, though you’re not quite sure that ever arrives.

However, it’s in the themes and lyrics of Rachel Davies – her voice aerial and delicate – that the record starts to open up about its own secrets. If Violet Cries suggested old folk tales told while sheltering away from the heat of war, then the similarly cryptic messages that make up Wash The Sins Not Only The Face veer more towards surrealism, and suggest a journey away from that previous scene in order to find new purpose ("It’s all I can do to assemble myself") the shape of which Davies can’t be sure of. This search for clarity is reflected in words that constantly look towards a clear sky, "bleached in moonlight, bathed in bonewhite". Davies cites Sylvia Plath as an influence on this album, and that shows in an earthiness in her own words, evoking a strong sense of nature – though their semantics are hardened: "slate", "cobalt", "dumb mud" dripping.

The overriding notion of unidentifiable longing is represented most strongly in ‘Yellow Wood’, possibly the group’s most fully-realised song to date. It sees them at their most haunting and lucid, Davies’ calling out to be found becomes submerged under Daniel Copeland’s tom-heavy rhythms and the constellation-searching evocations of guitarist Thomas Fisher. Yet even as they look forward they’re turned back to the past; "it’s lonely in the shade that wicked memory makes", murmur the lyrics, and from then on the album is gradually pulled back towards previously-trodden tumult. In contrast to Violet Cries, which felt like it was raging against the dying of the light, Wash The Sins Not Only Your Face gradually allows itself to be overhauled and then smothered by the darkness.

Contentment on the journey is seemingly found on the unwinding expanse of ‘Putting Down The Prey’, only for ‘The Fall Of Glorieta Mountain’ to be subsumed by new doubt and – finally – ‘Smashed To Pieces In The Still Of The Night’s’ fiery seven minutes return the trio back to their turbulence. You can hear the distress as the band realise their wanderings have gone full-circle, the shape that finally looms into view all-too familiar. Ultimately it’s the breaking of a cycle that leads to change and, on this record of both progression and recollection, Esben And The Witch suggest that they haven’t yet quite achieved that. However, it’s their battle in trying to that make that happen that makes this such a fascinating listen.