Producer Brian Eno said one of the main technical difficulties he experienced during the recording sessions of the The Pace Setters album in Ghana was that Edikanfo group members could not overdub individual sections from their compositions. “As a thread in the weave,” the ‘parts’ did not exist on their own. Only when locked into everything else.

This insight serves to highlight why the expansive arrangements that make up the songs work so well on Edikanfo’s debut – and up until recently, only – studio recordings. There are powerful dynamic themes that develop, while at the same time a free-flowing looseness that is not determined by rigid structure.

Witness the drum solo during the breakdown on ‘Gbenta’ that does not lose any of the track’s momentum, and as the bass and other instruments join in once more, the fluidity of the movement exists in the moment. “What they’d given me was finished,” Eno later remarked of the tapes. “There was nothing else I could add.”

Already enthused by the music of Fela Kuti and his Afrobeat movement in neighbouring Nigeria, Eno jumped at the invitation of Faisal Helwani, Edikanfo’s impresario and manager, to visit and attend a festival in Ghana and produce the group. The group’s big band formation including guitar, bass and drums, and bolstered by horns, keyboards and additional percussion will have certainly appealed to Eno’s then ongoing search of what he had in mind for a “vision of a psychedelic Africa”.

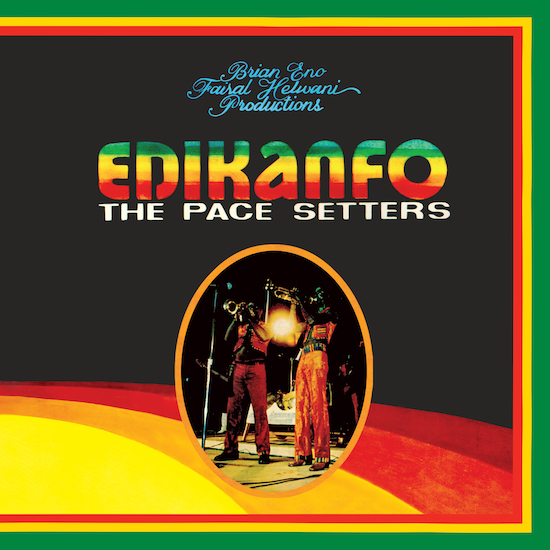

While the members of Edikanfo regularly played in various highlife, jazz and funk groups around Ghana during the height of disco’s popularity, as a group they combined their talents into a blend of danceable and big band sounds – that unlike their regular gigs, would eschew the clubs in favour of big stadium concerts, every few months. The eight-piece group referred to themselves as the ‘African Super Band,’ and their name itself is a straight translation of the album title and how they were regarded – the pacesetters, or people who lead.

The group played regularly in Accra at the Napoleon Club in the suburb of Osu, but band members could often find themselves out of pocket at the end of the night due to the way Helwani managed them – as they had to pay him to hire their gear for the shows.

The setting for the recordings followed Eno’s high profile work with David Byrne, both as producer on Remain In Light (1980) by Talking Heads and their 1981 collaboration My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts. Eno had also recently worked with Jon Hassell on Fourth World Vol. 1 – Possible Musics and Laraaji on Ambient 3 (Day Of Radiance) – both recently reissued by Glitterbeat, as is The Pace Setters. The avant-funk and experimenting with various different styles and influences of the work with Talking Heads and Byrne in particular no doubt prepared Eno for the task of the recordings with Edikanfo, even if by his own acknowledgement he had to make do with a less luxurious studio set-up than he was accustomed.

Still, the results deliver – and while a range of styles make up the six tracks, unsurprising given they were written by five different individual group members – and remains cohesive. The Afro-funk guitars and bass playing, disco keys and polyrhythmic drumming makes for a head-spinning force, with horns accentuating the key build-ups. The forward-thinking progressive nature of the music extended to the lyrical themes on the album, as sung by all group members, for example, opener ‘Nka Bom’ translates as togetherness with a message of strength in unity.

Following the album’s original release in 1981 a coup d’etat in Ghana by the end of the year put paid to planned touring of Europe and the US as group members scattered into exile around the world.

The group has recently regrouped and a new album is reportedly in the can forty years later. Once more touring plans have been put on ice. Who knows when their time will come? For those of us discovering these recordings there is no time like the present as the undeniable grooves sound as alive as ever.