Ed Askew is best known, if he’s known at all, for his obscure 1968 album Ask The Unicorn on cult New York label ESP-Disk, home to such pioneers of the city’s free jazz scene as Sun-Ra, Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, and equally out-there folk-rock acts the Fugs, the Godz and Pearls Before Swine. Perfectly suited to such esteemed company, Askew’s album – played on air by John Peel and hardly anyone else – featured him accompanying himself on the Martin Tiple, a ten-stringed instrument similar to a lute (or, according to Askew himself, "a baritone ukulele") which is notoriously physically demanding to play, a fact that contributed to Askew’s urgent, strained and tremulous vocal style. Later described as "the Holy Modal Rounders jamming with Skip Spence," Ask The Unicorn was soon as vanished and mythical as its namesake; Askew’s second album for ESP, Little Eyes, remained unreleased for 33 years, until De Stijl Records finally put it out in 2003, to a warm critical reception that sparked a revival of interest in Askew’s music.

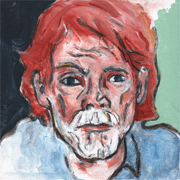

Born in Stamford, Connecticut in 1940, Askew studied Art at Yale from 1963, and mostly remained in the New Haven area till 1987, when he relocated to New York City. He carved an underground reputation as a painter and a poet throughout the 1970s and beyond, while continuing to compose and occasionally perform songs. His playing, however, was hampered by Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, the result of several years of earning a living by scraping down and re-painting houses. A small inheritance in the mid-80s restarted his musical career, allowing him to buy an electric piano, a few microphones and a four-track, and he began regularly releasing home recordings on cassette. He continues to pursue this DIY approach to this day, though it’s made easier now thanks to the advent of Pro Tools and Bandcamp.

Despite having briefly played in a 1966-67 psych rock band named Gandalf & The Motorpickle (what else?), For the World is Askew’s first album to feature any other players besides himself. They include three-fifths of the Black Swans, plus Marc Ribot, Sharon Van Etten, harpist Mary Lattimore and keyboard player Jay Pluck. Askew has previously recorded many of these songs on his solo releases, and these new versions, augmented by such a professional cast, are relatively slick and polished by his standards. Indeed, opener ‘Roadio Rose’ as performed here, could conceivably be a mainstream ballad hit, if delivered by a trained, conventional singer. Happily, Askew is neither of these things, and his imperfect but ambitious voice is what makes the song, and the whole album, special.

Askew also has a painter’s talent for imagery and symbolism; the black rider breaking silver chains amid the tumbling piano chords and tear-pricks of harp on ‘Roadio Rose,’ or the yellow bird and weeping clowns on the impressionistic ‘Drum Song.’ Elsewhere he’s an engaging storyteller, effortlessly turning incidents of ordinary beauty and quiet epiphany into songs that are at once intense and conversational, in the spirit of American poets from Walt Whitman to Frank O’Hara and Gregory Corso. As in their work, there’s a childlike innocence and wonder evident too, a quasi-religious joy in nature and the possibilities of love and life – witness for instance the repeated affirmations of ‘Blue Eyed Baby’, which also recalls fellow New York song-poet Baby Dee. But like Dee, and indeed the aforementioned great American poets, Askew’s visionary moments are never pompous or pretentious, but are delivered with a working man’s offhand modesty and humility, and a gentle sense of humour.

‘Gertrude Stein’ weaves in musings upon the poetess’s famous "a Rose is a Rose is a Rose" line with comparisons between Askew’s own New York street life and the glamorous-seeming existence of those bohemian pioneers of nearly a century earlier. Sometimes he comes on like Jeffrey Lewis’s equally wide-eyed granddad, documenting the everyday minutiae of a life, the changing seasons and the observations of a moment, with a poet’s commitment and discipline. The songs are intensely personal, as on the moving ‘Moon in the Mind’ and its "don’t cry, Billy," refrain, but also somehow universal in their humble portrayal of the human condition.

Spare, affecting and hauntingly melodic, For The World is a timeless record, looking back only in a human, personal way – not to some lost golden age, but over a life lived, with all its ups and downs, losses and gains. "I’d like to not have to think about the 60s or the 70s," he sighs on ‘Gertrude Stein.’ For the World then, is not just for a small coterie of aficionados and record collectors, but for everyone, and for all time.