Back in 1984, the year of Ocean Rain’s original release, there were two UK bands, poised to take their bombastic, chorus-laden, almost certainly soul-selling updates of the sparse post-punk aesthetic to the world’s arenas. One was U2 and the other was… er, Simple Minds.

Echo and the Bunnymen were, unbelievable as it may seem now, widely tipped to comfortably eclipse both of those groups. Drawing on many of the same core influences – Bowie via Joy Division with a dash of Television – the Bunnymen also had a clutch of Really Catchy Singles and that most essential (but deeply un-post punk) US-cracking trait, Being Able To Cut It Live. And in singer Ian McCulloch, simultaneously channelling Iggy Pop and Scott Walker from beneath the best haircut of the 80s, they had a genuine pin-up pop idol pseudo-poet up front.

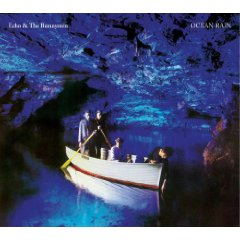

Released at a moment when the world seemed theirs for the taking, Ocean Rain was famously touted in magazine adverts (and regularly onstage by McCulloch) as “The greatest album ever made”.

Almost inevitably, it isn’t even the greatest album the Bunnymen ever made. But it remains the clearest glimpse into every other parallel universe but this one, where Bono is the has-been, phoning in the hits from the mid-afternoon slots of the festival circuit, while McCulloch plays golf with Barack Obama.

While McCulloch remains the only Bunny-face anyone but die hard fans can picture clearly, guitarist Will Sergeant was the band’s real creative force, and Ocean Rain is very much his record. Scattering an intricate lattice-work of chimes and shimmers over the windswept orchestral arrangements that underpin most of the album, he musters a curiously non-macho form of guitar heroics. From the flamenco stylings of ‘Nocturnal Me’ to the cod-eastern melodies and atonal scrapes and clanks of the lamentably titled ‘Thorn of Crowns’, he revels in exploring defiantly un-rockist ways of playing the guitar.

Even when playing it relatively straight on the jangle-pop ‘Crystal Days’, Sergeant casually up-ends the table and pulls out a bracingly experimental instrumental break, with squalls of feedback screeching over bassist Les Pattinson and drummer Pete de Freitas’s suddenly liberated rhythm clatter and overdubbed pipe-banging percussion. It’s these kinds of “what the hell just happened?” moments that still make Ocean Rain a startling listen twenty-four years later.

Time has been rather less kind to the young McCulloch’s brand of metaphysical lyrical cobblers, unfortunately, and for every dazzling leap of imagination the band make sonically, McCulloch takes an equivalent lurch backwards into the kind of risible nonsense that would have embarrassed even rock’s greatest charlatan (and McCulloch inspiration) Jim Morrison. “Blind sailors, imprisoned jailers,” he wails on opening track Silver. “God tame us, no-one to blame us” he goes on. What can it mean? “Food for survival thought”, he solemnly informs us.

Plainly, the more recherché lyrical concerns of the record had much to do with the band’s then-unfashionable immersion in LSD (as documented in Julian Cope’s excellent book Head On), with nosedives from the absurd to the utterly unfathomable being a regular feature. The line “C-c-c-cucumber, c-c-c-cabbage, c-c-c-cauliflower, men on Mars” is delivered with the conviction of a revivalist preacher, and vacuous images of “starry skies” and “blue horizons” and – amusingly – “bigger themes” abound. Presumably, you had to be there.

To take a more generous view, however, the Bunnymen were always far more about evocative form than substantial specifics, and McCulloch brings one of pop’s most idiosyncratically beautiful white male voices to the table. Able to pull off a gravelled croon like his hero Leonard Cohen, but also turn on a penny to a melodramatic Bowie-like yelp, young McCulloch positively soars throughout this record.

And where it all comes together, well… it’s still bollocks, but good lord, it is brilliant bollocks. ‘The Killing Moon’, both the centrepiece of the album and the band’s greatest single, still sends a shiver down the spine, with its distraught-yet-ecstatic surrender to “fate up against your will”. It’s still McCulloch the Shaman, but this time brooding over infidelity rather than a bunch of Philosophy access course set texts, and is all the better for it.

Closing track ‘Angels and Devils’ is a gentler take on the same worship of doomed romance which is the cornerstone of the lone young male psyche, and the real core of the Bunnymen’s appeal. McCulloch was always better in this kind of territory, the natural aesthetics of his voice and narcissistic inclinations of his ego enabling him to drag something genuinely affecting out of a fairly hackneyed wounded romantic schtick.

The penultimate title track is probably the only real fumble of the album. A self-conscious attempt at writing A Proper Grown Up Song, it most anticipates the tedious mid-tempo dirges of their current incarnation. And if you ever wanted a single song to blame for Richard Ashcroft’s most turgidly navel-gazing moments, it’s surely this. Tellingly, Sergeant is hardly present on it all, until he appears in the closing moments with a spiralling melody that doesn’t quite rescue the whole enterprise.

And then, blinking in the cold light of day, it’s over. What happened next was that U2 performed at Live Aid, playing a shamelessly conservative covers set featuring ‘Walk on the Wild Side’, ‘Sympathy For The Devil’ and ‘Ruby Tuesday’ and ran off with the 1980s Rock God prizes. And as McCulloch has since admitted, the Bunnymen ditched the acid and sonic adventurousness in favour of c-c-c-cocaine and hummable but inconsequential indie disco fodder like ‘Lips Like Sugar’. And by this time, The Smiths were on the rise, with a young guitarist called Johnny Marr who could comfortably out-Sergeant the Bunnymen guitarist, and a singer with a pen so sharp that peddlers of mystic guff like McCulloch suffered a collective Emperor’s New Clothes moment, from which MCulloch at least never really recovered.

Even more disastrously, at the exact moment they should have been globally gigging the living daylights out of Ocean Rain, they fell out with their record label, and decided to spite them by disappearing on an obscure Scandinavian tour playing a covers set of their own, cranking out Doors songs to bemused and shrinking crowds. And that was that, bar an eponymous final album nobody cares about before an 11 year hiatus (I’m disregarding the McCulloch-less album from 1990 here, for which anyone who’s heard it will no doubt be grateful).

Since reforming in the late 1990s, the band have released a stream of forgettable “mature” albums that will leave people hearing them for the first time utterly perplexed as to what the fuss was about. And comparing the Ocean Rain-era Bunnymen – McCulloch memorably clawing his own clothes off in front of a startled Top Of The Pops audience while the band tore up a majestic storm behind him – to the current incarnation – McCulloch standing indifferently at the mic, fag in hand while Seargent rakes out pleasant mid-tempo rock – is holding them to a tough standard. But it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that at the crucial moment, the Bunnymen simply gave up. However, for a short while, they blazed brightly, and this was the most thrilling moment of the Bunnymen adventure.