Co-released by Matthew Herbert’s Accidental records and Beacon Sound (home to the likes of Colleen, Daniel Menche, and Hans Otte), Right to the City finds composer Dominic Voz channeling a glitchy, minimalist blend of uplifting electronics, snatches of spoken word, delicate piano, and playfully saccharine strings. It is a rather intoxicating sound world, and deliberately so – a zestful, bubbling tableau of reverb-drenched arpeggios and restless warbles, the sonic equivalent of watching a carefree sunset from the rooftop of the utopian inner-cities of the future.

Clinical synths mingle with repetitive phrases, a certain Reichian charm at play, with each of the short tracks exploring a rich mosaic of contrasting elements, all held together by the rubbery, hi-fi production. Earthy bursts of field recordings and abstract instrumentals proliferate a busy palette, swarms of jittering texture rising up to obliterate the melody – capturing, for a moment, a single note or fragment in a beat-repeated bubble. The use of the voice is both integral to the album and intriguingly implemented. Breaths and snippets of French and English weave between the hissing, stuttering shards of instruments, more ornamental than structural necessity. The same might be said for the beats, too – the nature of Voz’s approach is such that the lively, clipped percussion serves to accent the already fractured synthesis, prioritising emergent, secondary rhythms over any desire to keep time.

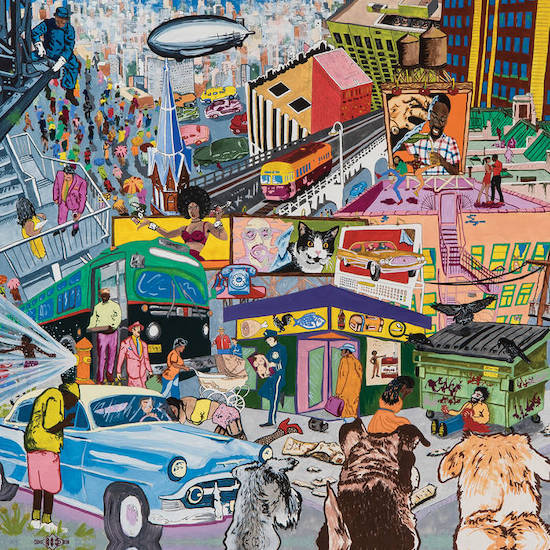

Although in no way derivate, Voz nonetheless slots neatly into a broader scene of contemporary electronic composers. There are recognisable shades of Ensemble Economique or T. Gowdry, whilst those familiar with the eclectic Maxwell Sterling will no doubt recognise a similar method of interweaving potentially incongruous timbres. Yet what might be considered an impeccable sense of focus, nonetheless risks fostering a certain sterility. At times, Voz’s Juno-esque synths and perfectly captured strings feel so void of imperfection as to be torn straight from the General Midi playbook, a spritely tableau of shiny, unblemished sounds. Thankfully, the lifelessness that often goes along with such things is offset by both a penchant for awkward rhythms and the composer’s fundamental inability to sit still. Like the erratic painting of a sugar-addled child, the album as a whole is downright skittish, frantic in its appropriation and disruption of such jarringly pleasant material.

Glitching without ever courting the unpleasant, Right to the City revels in its glossy, futuristic aesthetic. What the press release describes as “a process of fractured storytelling” feels entirely accurate, for it is an album that embraces the dichotomous energy of its city-subject, alluring and formidable alike. And, much like the modern city, it is a work of astonishing synthesis, pulling together a broad range of well-rendered textures to produce a surprisingly complex journey to a beautiful, if occasionally overwhelming, future.