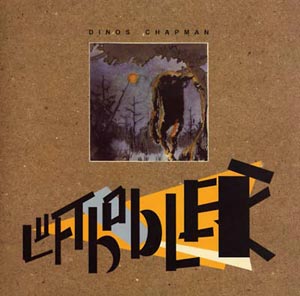

It’s understandable that certain quarters have offered a rather frosty reception to Dinos Chapman’s entry into music. Luftbobler has arrived heralded with the sort of broadsheet attention and fanfare that few inhabiting the worlds where the music it contains originates from – electronica and techno – could hope to command after ten years in the game. His cheekily and rather provocatively naming the album after the bubbles in a Norwegian Aero bar – a word that just so happens, as he told Luke Turner in a recent Quietus interview, to sound "German, and quite Nazi bomberish" – probably isn’t liable to help his cause either, given that it’s flippant enough to seem like yet another middle finger brandished in underground electronic artists’ direction. (Of course, given his history, it’s hardly a surprising choice of title, loaded as it is.)

Still, that hardly constitutes a concrete reason to damn it, and once you clamber past the "famed artist makes move into music-making" baggage (both the positive and negative aspects thereof), there’s some beguilingly odd material on Luftbobler. For a start, barely any of its contents qualify as more than sketches, using brief snatches of piano, insectoid beats and all manner of synthetic clunks and blurts to explore single themes across the course of two to three minutes. No track is longer than four minutes, leaving them precious little time to unravel and reveal whatever underlying ideas drive them. It’s as likely that there simply aren’t any – the album was made at night over a long period of time, via Chapman messing around on various pieces of software, and its track titles, playful as they are, serve to give very little away.

His treatment of whatever human material is present within his tracks is similarly obtuse: "I like the sound of voices," he said in the same interview, "but I’m not necessarily so interested in what they’re saying." Indeed, Luftbobler is riddled with traces of the human voice, downpitched, shredded, half-hidden in the gloom. In many tracks they feel like the core motifs around which the music has been written to hinge. ‘Whatever Works’ features a male (or I suppose it could be female) voice plunged several octaves down the register and slowed to a grim burble, violently pushed into the foreground. Yet again it’s impossible to decipher, its linguistic content masked, so the additional musical material that’s draped across it feels all the more detached from concrete reality.

Dinos and his brother Jake curated an edition of All Tomorrow’s Parties in 2004. Looking back through that line-up now serves as a pretty comprehensive road map of influences by which to understand where Luftbobler came from: the heavily effected peals of brass on ‘He Has No Method’ and the splintered voices of ‘Pizza Man’ are pure Throbbing Gristle, the spiraling beats of ‘So It Goes’ and ‘Sputnik’ rifs on Tri Repetae-era Autechre, the bouncing-ball piano figures that crop up occasionally are reminiscent of Richard D. James’ music. There’s nothing on Luftbobler that qualifies as new – which is almost besides the point for a record that feels like one person’s investigation into the workings of the music they love. Although perhaps that is one reason why it fails to unnerve as much as you might expect: what’s perhaps surprising given Chapman’s reputation – and could definitely be seen as either positive or negative depending on your inclination – is just how not sinister much of Luftbobler is.

That doesn’t stop much of it being rather beautiful. ‘Reaktorsnuhsnuh’ isn’t even two minutes long, but its main feature is a tiny and fragile, Aphex-ish piano motif that hovers tentatively in mid-air, feverishly waiting for something to happen and rouse it into further action. That it doesn’t works in its favour, transferring that built up tension directly into the next track. ‘Where’s The General’ is a deliciously slight house track, powered by a muffled four-to-the-floor thud that hints towards the dessicated deep house of early Workshop releases, and crowned with drifts of synth fog so miniscule they’re almost not present at all. It’s just a shame it’s so short – it would be intriguing to hear Chapman stretch its ideas out across an EP’s worth of low-key club music. This same issue encapsulates Luftbobler on a whole, responsible for both its weakest and strongest aspects. As it stands its best moments feel like tantalising snacks, touching on interesting ideas that could be developed further were Chapman to go on and make another full-length, rather than thoroughly fulfilling meals in their own right. The Aero metaphor seems apt: each bubble contained within Luftbobler is pleasurable, light but short-lived.