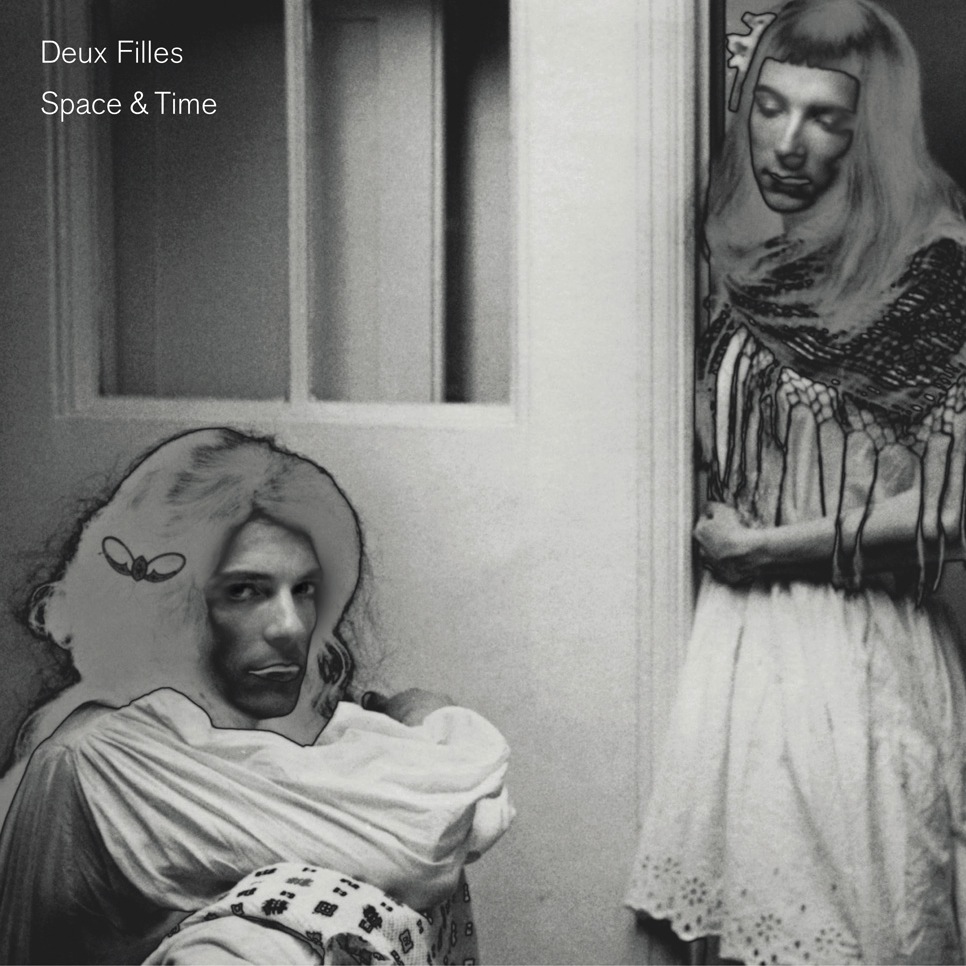

The best thing about some fictive characters is they never age. They remain frozen in aspect, cocooned in the womb of an imagination, even as the mind shows mortal signs of deterioration. That’s a premise to keep in mind when discussing Gemini Forque and Claudine Coule, the affected drag duo fantasy fabricated by Colin Lloyd Tucker and Simon Fisher Turner and preserved without activity for nigh on 33 years. Like Marcel Duchamp donning the Rrose Selavy get up, there’s a regal masquerade projected by Forque and Coule, in the photos that adorn their first album Silence & Wisdom, as if these two characters were estranged debutantes eluding aristocratic life for a precarious bohemian freedom. The record itself seems to exist outside of any criteria, withholding an immersive ether-elegance that wanders through lulling soft-pedal jangle, surreal burrows of ambience and a maze of sporadic spoken word samples which sound like the orations of benign phantoms. So complete and alluring is their world that the frolicsome yarn they’ve spun – of two arch boys essentially playing dress up – becomes one you want to believe in. It’s a transformation Tucker himself has at one time signalled as all consuming: "we became Claudine and Gemini".

Tucker and Turner met through Matt Johnson of The The, an early incarnation of which Tucker left in 1981. Turner spitballed the concept of ‘becoming’ two French girls, an idea Tucker was receptive to, on account of the effect it would have on how the project was perceived. The idea had come to Turner in a dream, and the roots of its realisation were fortified by Turner’s interest in women’s rights, not to mention the supposed license for free play in live performance that the fraudulence would permit. Gemini (Tucker) was to be a "spaced out Alice In Wonderland figure" while Claudine (Turner) was imagined as exuding a contrastive sense of intelligence and sophistication.

Abetting their imaginations, such onstage personas seem to have afforded a deflection, alleviating the burden of presenting their true selves, and allowing the nomadic and aerial qualities of their music to flourish, a music which aptly matched the blithe guises cooked up in their heads. 1983’s Double Happiness followed swiftly in the wake of the previous year’s debut, just as liberated, characterised by psychedelic poise and evaporating forms, yet different, supplanting the sheer idylls of Silence & Wisdom for frontiers that felt faintly darker.

With Space & Time it’s as if the interim between then and now hasn’t registered at all. On opening track ‘Her New Master’, a tape is heard winding into action, as if playing such a tape once again has unlocked the essence of Gemini and Claudine, and the track is a florid accompaniment to their reawakening. It’s a fleet, wide-eyed introduction with the sampled enunciations of what sounds like a papal clergyman expressing benediction from a distance above incipient, amorphous shades of neo-classical grace.

‘Belle’s Bell’ expands the enigmatic trace of a shadowplay narrative with a half-heard telephone conversation conducted in French (‘ello Claudine?’) eventually obscured by an ever swelling ambient-fog and bells which sound like the atmospheric commotion of buoys in a dock detecting some strange underwater presence. This is as good a time as any to emphasise the variance of the locations used for sourcing some of the sounds which frequent Space & Time. Nicaragua, Japan, England, Scotland, France and Wales have all in some way fed into the whole, a range which might account for the broad ambit that defines the record, from – for instance – a vaguely Orientalist cycle on ‘Song For Ozu’ to the playground rustle, hollow echo and undertone of Spanish soliloquy on ‘Mata Laya Pata’.

Unstructured whimsicality, like an incidental, oddball lullaby characterises ‘Mandy’s Playroom’, but it’s only when we arrive at ‘Horsebox Parade’ does a quietly overwhelming affect – in tradition with the duo’s finer moments on earlier records – begin to take shape. This continues on ‘Moon Starer’s Return’, another interlude, but one that defies its brevity with a lush baroque procession, as if Joe Meek were to offer a 30th century version of ‘Greensleeves’. Meanwhile ‘Prayer For Vince’ shares a similar mood, conveying the elevated feel of a score and thereby revealing some semblance of Turner’s work as a soundtrack composer.

Yet due to the discursive course undertaken across these twenty four tracks, such qualities are more like nebulous tracings than categorical imprints. Just as an idea of where we’re headed seems stable – in this case melancholic orchestral soundtrack-esque themes – disruptive vignettes derail proceedings, as on ‘Shell-Like Cornice’ and ‘Mouth Popsicle Explosion’, the former a chasm of furtive, overlapping whispers and the latter a strange stopgap of Didgeridoo-like derangement. It’s perhaps what makes the record so appealing. It’s an open, unpredictable book that seems to lead down one corridor before slipping into an altogether different one, yet these oblique wanderings still feel part of the same remote construction.

With ‘Preparing Wet Piano Tuna’, there’s more divergence. This time, a solitary piano makes sonorous ripples around domestic background noise and an elderly voice. It feels like a momentary glimpse into the private world Gemini and Claudine might occupy, in this case it’s easy to imagine an old piano being delicately played in an ornate drawing room. The wonderfully titled ‘Oh How We Laughed (With The Capsizing Girls)’, on the other hand, combines judicious formality (strings and silence) with informal eccentricity (interjections of a laughing crowd) bringing together what often characterises the paradoxical instincts of the record.

In the final throes, those tendencies continue. ‘Happy Clappy’ and ‘Spooky Gumbo Trance’ fulfil the expectations of erratic forays suggested by their titles while ‘Soft Crushed Love’ and ‘Deep Snowdrop’ are some of the more exquisite moments of structured repose in these latter stages.

From there the disparity between each track seems to heighten. An elderly woman reflects on her life, detailing a time working in a pighouse on ‘Pighouse Parachute Blues’ whilst a funereal backing trudges on, spaced out crepuscular glow shines dimly on ‘Treasure Trove Of Memories’, Spanish guitar soloing in a hushed exotic location resounds on ‘Gigante Beach (And The Giant Pig’ (a beach located in Nicaragua); all together these tracks seem to exist in different worlds entirely, but they’re brought into accord through a capricious, disorderly sense of arrangement and an even-tempered restraint. Out of such measured eccentricity comes a pliant, curious form of instrumental chamber pop that favours a vivid dream logic above straight forward linearity.

The concluding cycle features ‘The Five Sexes’, a cryptic demonstration tape with a monosyllabic definition roll call of "Male", "Female", "Hermaphrodite", "Mermaphrodite", and "Fermaphrodite", a theory lifted from a contentious paper written by sexologist and gender identity academic Anne Fausto-Sterling. In it Sterling discusses the etymology of Hermaphrodite, a word which ‘comes from the Greek name Hermes, the messenger of the Gods, the patron of music, the controller of dreams, and Aphrodite, the goddess of sexual love and beauty’. These meanings are entirely befitting to Space & Time, a record by two men embodying female characters, characters which seem to exist apart from them, in an absolute false front reverie of elaborate counterfeit chic. Over thirty years since supposedly "disappearing without trace during a trip to Algiers in 1984" and their fiction of playful mystique is very much intact, populated by a music as mutable, subtle, and beautiful as ever.