Breathing. The first instance of life. The bodily movement that causes existence. An activity that is so potent, it can transform survival into art. Colin Stetson has spent his entire life pushing the musical potential of a seemingly limited instrument like the saxophone way beyond its bounds by mastering the primal capacity to inhale and expel air to an unparalleled level.

Growing up in Ann Arbour, Michigan, Stetson was to all appearances destined to become a painter and a special effects expert for Hollywood sci-fi and fantasy films. But then, at age nine, he took his first steps towards the saxophone, and at age fifteen, he perfected circular breathing. When he demonstrated his mind-bending drone warm-up exercises to his college professor, none other than the chair of the World Saxophone Congress, Donald Sinta, the teacher felt the urge to leave the class before it had even begun. He returned after a week to show his pupil that he had learned to do the same. Along with playing the sax, he pushed the possibilities to their limits. For many years, Stetson trained in wrestling, a sport that may seem unrelated to music but actually calls for much of the same things – discipline, skill, and application of a set of defined rules to be applied differently in various contexts – as the improv he was so eager to accomplish with his instrument; the same might cloaked in a graceful, coordinated movement; the same fortitude and strength to maintain balance. The same unwavering yearning to breathe.

Stetson uses the saxophone in a way that goes well beyond merely playing it. It is an action that both of the bodies—the human and the steel one—participate in. Whereas some artists might struggle to keep their hands as quiet and soft as possible, Stetson’s dynamism changes the sound of pressing the keys into an accompaniment for his solo performance. Powerful. Muscular. Elegant.

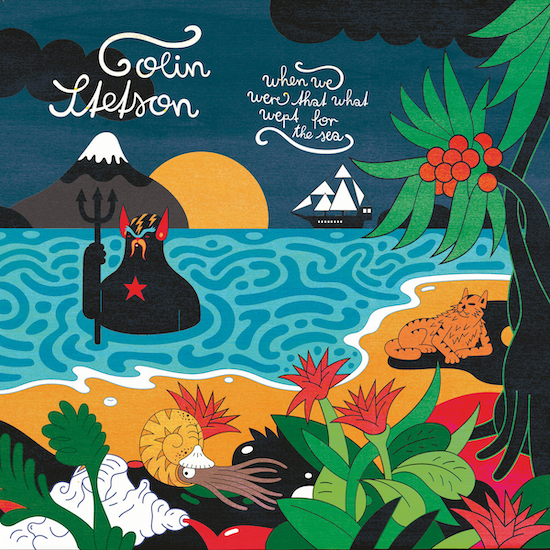

When We Were That What Wept For The Sea originates from an entirely different place than the previous Stetson album. It is an urgently composed, nearly spontaneous dedication to his father, who recently died somewhat unexpectedly. A disruption in the musician’s otherwise systematic and organised creative process. A lengthy piece that lasts more than 70 minutes, it’s divided into 16 tracks without any written introduction or justification.

A methodical listener who frequently returns to Glenn Gould’s 1981 recording of Bach’s Golberg Variations, as well as Irish and Scandinavian folk, all these inspirations are made very clear by the saxophonist in the album’s soundscape, which also features Iarla Ó Lionáird on vocals, Scottish smallpipes by Brìghde Chaimbeul, and guitars and strings by Toby Summerfield and Matt Combs, respectively.

Stetson leads us on a voyage of reminiscence and grief, much like a marine adventure, full of suspended moments, foggy hazy shores, and battles against the stormy sea. A Romantic Sturm und Drang work where beauty and horror, fear and longing can exist at the same in the sublime of nature. Dark abysses open after airy and dilated moments; breathes, touches, and mechanical sounds counterpart abstract movements. The spoken lyrics of "The Lighthouse V," which put the musical images into words and inspired the album’s title, follow a crescendo that rises until "The Lighthouse IV"’s explosion, where all the tension and misery find its desperate shout.

But there is no calm at the end of the journey. Only peace, maybe. And the time to set sail again.