There’s a scene in Twin Peaks: The Return, David Lynch and Mark Frost’s 25 years later reprise of the surreal mystery series, that’s haunted me since its transmission in 2017. Kyle MacLachlan’s Special Agent Dale Cooper, finally freed from the extra-dimensional Black Lodge and returned to present-day America, now finds himself trapped in the life of sleazy insurance salesman Dougie Jones. Virtually comatose, Dougie/Cooper stumbles through each day with little understanding of the world around him. At the end of episode five, however, he’s confronted with a statue of an archetypal lawman: strong, stoic, arm outstretched with gun in hand. It seems to stir something up inside of Cooper, as if saying: “This is who you used to be. What happened to that guy?”

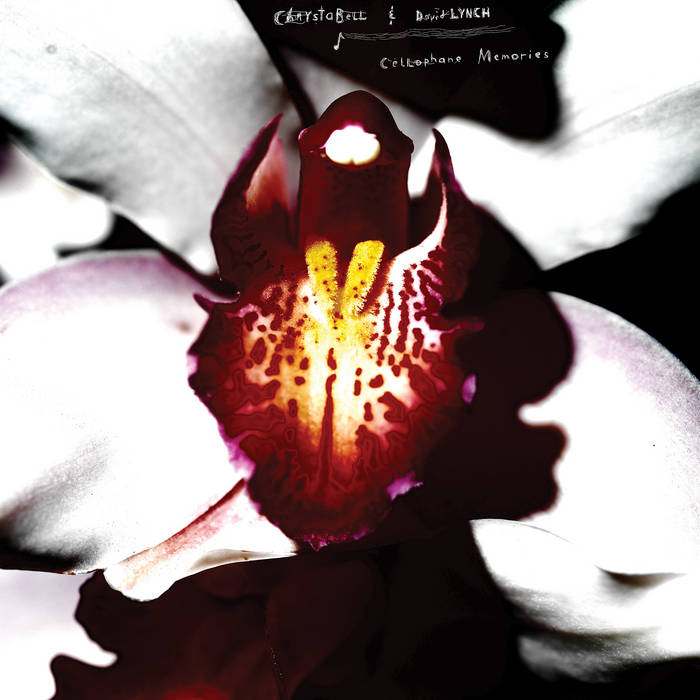

It’s a quietly melancholy scene, one that nails the powerful yet intangible nature of memory, a theme that’s repeated on the latest album from Lynch and vocalist Chrystabell. Lyrically, the ten songs on Cellophane Memories are made up of moments and reflections – usually romantic, frequently mundane (“For dinner it was meat and potatoes / I went bed early”). But where the duo’s first album together, 2011’s This Train, was a relatively conventional dream pop record, all smokey vocals, oceans of reverb, and languorous guitar licks; Cellophane Memories is harder to get a grip on. Chrystabell’s vocals, previously the unambiguous focus of every song, are here layered, cut-up, and reversed, often to the point where they become indecipherable.

That’s in part due to the nature of its creation. The starting point for Cellophane Memories came with the discovery of a trove of forgotten recordings, eventually attributed to the trio of sound designer Dean Hurley (whose collaborations with the producer Romance have a real sense of the everyday uncanny and feel like close cousins to this album), the late Angelo Badalamenti, and Lynch himself. Using these pieces as a starting point, the duo improvised lyrics and recorded them quickly before assembling the final tracks into a series of abstract compositions that seem to bleed into each other.

‘So Much Love’ is a pastoral romance that contrasts the epic sweep of Badalamenti’s synths with the intimacy of Chrystabell’s aching sighs. It’s one of two tracks on the album featuring the great composer and demonstrates his mastery of unsettled moods perhaps for the final time. ‘The Answers to the Questions’, meanwhile, is exactly what you’d expect from a Lynch/Chrystabell/Hurley collaboration, with the latter’s distantly-chugging-train percussion underpinning a lyric that borders on Lynchian self-parody: “There was a feeling / a feeling of falling / she felt she would never find the answer / the answer to the questions.” The song ends with the nameless she slipping into a dream because, well, of course it does.

On ‘Reflections in a Blade’ that dream becomes a nightmare, with the mostly reversed vocals layered on top of each other to create something profoundly sinister. Happily, the song ends with its protagonist waking just in time to enjoy moments of unabashed joy on ‘Dance of Light’ and the closing ‘Sublime Eternal Love’, both of which foreground Chrystabell’s voice more stridently. On the latter she harmonises with herself, repeatedly intoning the title phrase against a backdrop of angelic synths that, to invoke Twin Peaks one final time, can’t help but recall the closing scenes of Fire Walk With Me, as doomed American icon Laura Palmer’s tormented spirit finally achieves some form of grace and ascends to Heaven, the White Lodge, or whatever else comes next. Like all of this hypnotically strange album, the song’s ethereal beauty lingers in the mind like a dream or a memory.