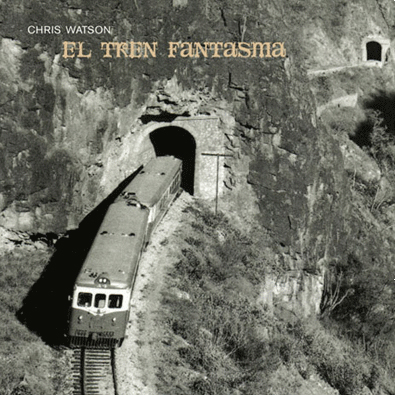

The fourth episode of the fourth series of the BBC’s Great Railway Journeys was broadcast on the January 26th 1999. Presented by chef Rick Stein, it featured The Ghost Train, the now-defunct railway which travelled across Mexico from Los Mochis on the Pacific Coast and over the country’s spine to Veracruz in the east. This continent-crossing railway, part of the Ferrocarriles Nacionales de México (FNM), had to climb 8,000 feet, travel alongside canyons, through ranch country and pine forests, and skirt shanty towns. Chris Watson, sound artist and founder member of Cabaret Voltaire, was working as audio recorder for the BBC on the programme. He spend a month travelling up and down on the Ghost Train, recording the sound of the railway, the people who rode on it, and the landscape through which it travelled.

Yet El Tren Fantasma is so much more than a field recording of that trip. On that simple level, Watson’s technical brilliance is in creating depth and space in sound. You actually feel the train coming towards you in ‘Los Mochis’, while listening to the ambient, relaxed moments – conversation, birds tweeting – the complex, three dimensional sound places you in a ghostly, auditory diorama.

There’s the great myth that nature is silent. Throughout, we hear the sound of wind in trees and grass, birds calls, weather. The Ghost Train is an interloper, human but unnatural, a giant metallic other clanking through the landscape. In fact, nature often sounds just as (if not more) menacing than the machinery and ephemera of the railway. ‘Crucero La Joya’ is a case in point, flies buzz, a rattle comes and goes. The affect is startling, even sci-fi apocalyptic. Penultimate track ‘El Tajin’ begins with a cacophony of animal and insect sounds, oppressive and seemingly recorded at night. Without the certainty of the train, all this undefinable noise leads our minds into fear of the unknown. Watson is recording the landscape before it was tamed by the demystifying, ‘civilising’ influence of our technology.

Is this music? Musique concrète and industrial opened the debate over whether mechanical, unmelodic sound could be appreciated and enjoyed by a listener as musical form. It’s a debate that will no doubt continue, tediously, until long after the apocalypse humanity is divided between those who found acoustic guitars amidst the ruins of our cities, and the rest of us who will enjoy the clatter of rocks on metal detritus.

Melody, structure, rhythm and atmosphere emerge and sink into the field recordings. Indeed, a strange result of repeated listens is that the musical elements that seem to come to the fore. Some of ‘Los Mochis’ electronic pulse is reminiscent of Throbbing Gristle’s Second Annual Report, the trebly crescendos in Los Mochis suggest Stephen O’Malley and Peter Rehberg’s KTL. The train’s horn on ‘El Divisadero’ blares past before disappearing into a deep, bass thrum, making a tunnel of your inner ear. When it emerges, the wheels on rail joints become a one-two beat, a warm enveloping hum descends. It wouldn’t sound out of place delivered by, say, The Haxan Cloak or Brian Eno.

In El Tren Fantasma Chris Watson creates an evocative sonic portrait that juxtaposes the human-made sounds of the railway and the surrounding landscape. Now, Google searches for Los Mochis to Veracruz will tell you nothing about a railway, but simply turn up details of cheap air fares. Aircraft noise (that bugbear of the field recorder) 30,000 feet above the sounds of the Mexican terra firma would hardly have the same resonance as this. As the wild interior of Mexico now reclaims much of the railway’s trackbed, Chris Watson’s record is haunting, powerful tribute and memorial to a marvel of engineering and the people who built, worked and travelled upon it.