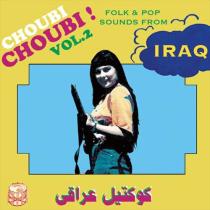

This excellent LP is a follow up to the original Choubi Choubi album that Mark Gergis put together in 2005 for Sublime Frequencies. It features a wealth of Iraqi folk-pop dance recordings from the 1980s, 90s and early 2000s – with all of it recorded under Saddam Hussein’s rule. And just in case there’s any chance of a casual listener missing the point of this (it’s never just about the music, man) the compiler and artist spells it out in the liner notes: “What has happened to Iraq since the 2003 US invasion and eventual occupation? Endless death, destruction and chaos, the complete take-down of a functional sovereign secular government [regardless of your opinion on that government], puppet installations, contrived sectarian divisions, the wholesale looting of culture, rampant opportunism, and apparently no lessons learned – all at the Iraqi people’s expense.” So this is music from the near past – from happier cultural times under Hussein. Of course, it’s a provocative political statement and not entirely clad in iron – music produced under the previous regime was institutionalized and it is undeniable that music continues to be made in Iraq now, it’s just that in 2013 musicians and artists are more likely to be the victims of violence or murder by extremists and more music shops and concert venues have been targeted successfully since 2003 by bombers.

Unlike his recent Syrian compilation for his own Sham Palace label, Dabke: Sounds Of The Syrian Houran, this music wasn’t tracked down directly from source but instead via the diasporic Iraqi community in Detroit he spent some of his youth in. (He hasn’t been to Iraq but some of his collection of cassettes is from Syria near the Iraqi border.) And if choubi on paper sounds similar to dabke, the two styles are analogous; the former is also popular at weddings, as well as in nightclubs and parties thrown by Iraq’s gypsy community. The outstanding feature of the music – created on fiddles, double reed instruments, bass, keyboards and oud – are the rapid fire blast beats created by the miniature hand drum called the khishba or zanbour (Arabic for wasp). One of the most stunning examples of the numerous effects that can be created by this humble instrument can be heard on ‘Instrumental Choubi Segment’ by Obeid Ensemble. It may be a percussion instrument of nomadic origins but in the right hands it can sound like the most futuristic of electronic synthesizers, carving out wild polyrhythms and textures that bedevil the ears like numerous ray guns misfiring at once, before being used gently and sparingly to open up acres of space. (Some of the more recent examples of choubi do create similar effects using synthesizers but due to the skills of the khishba players, the compression of the recordings etc, it’s often impossible to tell the difference.)

Personally I couldn’t help but notice the similarity between the terms choubi and chaabi (the popular Egyptian folk pop style currently undergoing a resurgence in popularity and rebirth as electro chaabi). On further investigation it turns out that both genres can feature the mawal or ornamental vocal improvisation which sets the tone for the song and is used to impart an emotionally charged atmosphere. And an emotional charge is something that the songs of Salah Abdel Ghafour provide. He features on three tracks, ‘The Brunette’ (“The brunette made me stay up all night. Where is the brunette? …While I waited, I’d say to myself, ‘Joy is waiting for me.’”), ‘Her Beautiful Eyes’ (“Oh brunette, I’m cured when I see you.”) and ‘Play Choubi On My Wounds’ (“You made me lose my mind. I don’t want to see you and have you break my heart once again.”). Sadly this great singer was killed in a car crash earlier this year and the compilation is dedicated to his memory.

Musicians are often outsiders of one stripe or another and things are no different in Iraq. While choubi music was actively encouraged under Hussein as part of the Baathist attempts to promote secularism and respect for heritage, being a musician was still frowned upon by middle class Arab society. Many of the artists on Choubi Choubi 2 are Rom Gypsy Iraqis (known colloquially as Kawliya), such as the deep, rich voiced Sajida Obeid. She was a famous nightclub singer in Baghdad in the 1980s, which meant that as well as issues of race, gender and class she was daubed with the additional stigma of moral turpitude and prostitution; even if it was only by association in the eyes of more conservative sections of Iraqi society. One of her tracks her is the ‘Mawal Introduction’ in which she welcomes people to her performance in her native dialect, thanking her friends for teaching her loyalty and good heartedness over a drone and a plaintive synthesizer line. What could be a particularly brisk and avant garde use of the khishba punctuating the track is actually celebratory gunfire recorded for posterity on this great compilation.