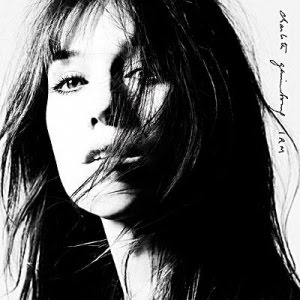

Last time we saw Charlotte Gainsbourg is a bloody memory that comparatively few will care to recall in detail, doubtlessly provoking sharp intakes of breath and much tight knotting of knees. In Lars von Trier’s spectacular Antichrist, Willem Dafoe’s "He" tried to coax Gainsbourg’s "She" to come to terms with the death of their son by making her confront the parasite on her recovery, taking her cripplingly obsessive fear of nature head on through isolation in their woodland cabin. Anyone who’s experienced the film can’t fail to remember quite how brutally the plan failed, but should rest easy that no such loin-girding is required to witness Gainsbourg try a similar approach to a real life trauma with IRM (‘MRI’ in English), her third album.

In 2007, she was hospitalised for a brain haemorrhage triggered by a waterskiing accident, and subject to a course of MRI scans as treatment. She’s spoken openly about the effect it had on her; her insistence on more scans after doctors had given the all clear for fear that they might have missed something, all the while supine becoming ever more attached to the harsh mechanical chomping sound of the MRI machine. Its unmistakable noise crops up in opening track ‘Master’s Hands’, chopping a duel with bleak desert drums, whilst she breathes, "Give me a reason to feel" over percussive rumbles and rhythms as bare as the skeleton she’s trying to reanimate. ‘IRM’ takes ghostly images of the mind as "a glass onion," intoned in her inimitably bucolic half-sung, half-spoken RP English – she’s killed off the femme fatale coo of 5:55 for a far more disconnected tone – whilst deadened drums build from ritualistic exorcism of the vespers within to a charged nightclub in negative. Her disconnection and scientific curiosity to see what’s inside make the process seem more like the mysterious practices of Eternal Sunshine‘s Lacuna Inc than a procedure thousands go through every day – the oddness of having to come to terms with one’s own body again is made startlingly real.

But for a record that promised to be intimate, without cause for disguise, the close-up seems to pan away there, lyrically at least. Despite being sold as an album by Charlotte Gainsbourg, Beck’s presence is less that of billed producer, and more collaborator, present in every frame. He wrote all of the English lyrics based on fragments and ideas fed to him by Gainsbourg, but seems to have widened the focus to extend far beyond the black leather couch. This is A Good Thing for the pair of them.

Beguiling as it was, no-one could have stomached another 5:55, at times nauseatingly overdone with lush strings and unrelentingly close-cropped, it served to prove that erotic prowess was certainly hereditary. And on Beck’s last record, Modern Guilt – despite being a return to form musically, as abetted by Danger Mouse – his grapples with war, conspiracy theories and global warming were so expansive that they dwarfed him somewhat. There was the fear that he might use IRM as a chance to tinker with the family jewels; to get his Jean-Claude Vannier on in an attempt to finish what he’d dabbled in on Sea Change‘s ‘Paper Tiger’. It’ll undoubtedly be written that ‘Time Of The Assassins’ and ‘Vanities’ satisfy that urge, but David Campbell’s (Beck’s father) string arrangements weigh with far more gravitas, in the latter employing harps to create the kind of richly detailed atmospheric darkness of which the great soundtrack composers might well find themselves envious. Instead he indulges his other well-known peccadillo – a love of bluesy ‘60s guitar and raw front porch singalongs peppered with references to the dustier side of American culture, from Greyhound stations to the Grateful Dead and notorious outlaw Belle Starr. The pair of them manage to strike their own personal balances, despite the end result being about four parts Beck to one part Charlotte – quite often her part will finish just over halfway through a song, leaving it to play out without her.

An instance where they do come together admirably is on their reprise of 1970s Quebecois singer Jean-Pierre Ferland’s ‘Le chat du café des artistes’. It’s a fairly recondite number, but hopefully this cover will change that. It’s a delight – an existential exercise in the French subjunctive tense about an artist’s irrational sense that being forgotten is such an ignominious end that they might as well be eaten by a cat and their remains thrown in the bin. The original has the typical pomp of a ‘70s chanson – Ferland’s voice rings with the theatrical raconteur tremble of a Joe Dassin type looking back on a long life, there’s a children’s choir and villainous flashes of brass. Beck and Gainsbourg strip these elements away, making it an unequivocally classy number that’s the kind of soundtrack Sam Mendes’ James Bond will hopefully deserve. But despite having Campbell on string arrangements, they either mimic or sample – it’s hard to tell – the original’s hysterical high-wire violins rather the reinterpreting them, which nonetheless contrast with her cool tones beautifully. Jude Rogers’ <a href="http://thequietus.com/articles/03447-a-decade-in-music-the-never-ending-cycle-of-the-cover-version" target-"out">marvellous Wreath Lecture on the rise of the cover version talked about artists giving covers their own stamp, but all they’ve done here is turn the temperature down. It raises some interesting questions – whether we’d permit artists held in lesser esteem such unimaginative covers, or whether they deserve applause for bringing a should-be-classic to the fore?

Then there’s the fact that almost all the French on this record is borrowed from others. Gainsbourg said in an interview with Les Inrockuptibles, "En Français, ce qui complique tout, c’est que le moindre mot me donne l’impression que mon père l’a déjà utilisé. Ça me bloque." ("In French, what complicates things is that even the slightest word has the impression of having already been used by my father. That blocks me.") ‘Voyage’ is the only song with any original French in it, borrowing its first three lines from the title of Céline’s Voyage au bout de la nuit, then piecing together an oblique tale of crumbling desert burnouts by word association over palpitating and complex hand-beaten rhythms and far off animal noises. And in ‘La Collectionneuse’, phantasmagorical with cosmic bell swirls and moaning vocal swoops, she corrals together bleak scraps of poetry by Apollinaire – to whom her father was compared by President Mitterand at the time of his death in 1991. For a record that’s supposed to be intimate, it’s hard to get much of a sense of who she actually is once the first two songs have passed. Her and Beck’s visions never do battle because, well… she never really seems to have much of one beyond offering him tidbits of other people’s words.

All this is noted through a magnifying glass though – despite falling apart a little in the inspection and intention, together they’ve made an incredible sounding record that sounds like little else around at the moment. Extraordinarily sensual without being pre-meditated, unlike its predecessor it achieves a complex beauty by excelling beyond just trying to be pretty, and for that it deserves respect.