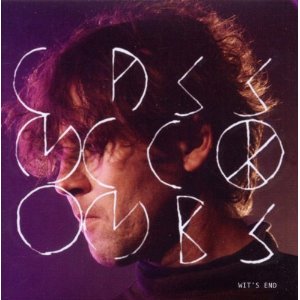

Cass McCombs is notoriously publicity-shy. He refuses to give interviews, and despite having already released four critically acclaimed albums, little is known about the man himself or the people or situations that inspire him. McCombs’ music is as hard to pin down as the man himself, and Wit’s End, the follow-up to 2009’s fantastic Catacombs, is no exception. After mining the maudlin jangle-pop of 80s indie icons like the Smiths and the Cure on his earliest releases, Catacombs saw McCombs trawling through a half-century’s worth of American music history – from the Everley Brothers to Willie Nelson to Todd Rundgren to Jeff Buckley – to create a work of creeping, shadowy beauty. Wit’s End is even more understated – and even more beautiful – than its predecessor; slower and sparser by far than anything McCombs has produced before, weaving elements of jazz and classical music into a collection of hymn-like compositions that are as mesmerising as they are fragile.

Of course, this being Cass McCombs, Wit’s End is far from easy listening. With seven songs ranging from five to ten minutes, the length, funereal pace and sombre tone of the album as a whole would test the patience of the most diligent Low fan, and as such the decision to open with arguably the most accessible track in the artist’s catalogue seems like some kind of perverse joke. ‘County Line’ is McCombs’ take on blue-eyed soul, a languid, electric piano-led ode to returning home to people that would rather he didn’t, and with its thick, warm bass sound and Brill Building "whoa-whoa-whoa" choruses, it’s easily as sweet as Catacombs‘ ‘Dreams Come True Girl’. There’s an unease at play though; the track doesn’t so much meander gently as deliberately drag its heels, McCombs understandably reluctant to going back to a place where – in a display of typically brilliant wordplay – he "can smell the columbine."

Once in its jaws, Wit’s End slowly and methodically eats away at the subconscious like a Venus fly-trap dissolving its prey. Stripped of any kind of percussion, ‘Buried Alive’ is driven by a cyclical, baroque harpsichord riff and an insistent mellotron pulse, McCombs cursing the nightmarish "hateful neighbours" that he can "smell but cannot see." The plodding ‘Saturday Song’ is very much wet weekend music, with a Surf’s Up-era Brian Wilson chord progression providing the tiniest ray of sunshine; ‘Memory’s Stain’ is darker still, a Satie-esque piano refrain turning round and round until an extended outro of wheezing accordion and woodwinds drag the track to its welcome conclusion. Listened to as a whole, the album is like one of those old French films where people sit staring through rain-streaked café windows; you’re not quite sure what – if anything – is happening, but its minimalism is hypnotic.

It’s all too easy to mistake a downbeat record for a depressing one, and whilst on the surface these songs sound about as cheerful as a suicide note, there is a sense of mischievous humour in McCombs’ lyrics that is closer to the literate surrealism of Bob Dylan or Tom Waits than the loathsome, self-pitying Snow Patrols of the world. Closing waltz ‘A Knock Upon The Door’, especially, with its epic, winding tale of a lovers’ tiff between an artist and his muse, echoes the likes of ‘Visions Of Johanna’ and ‘Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands’, while its slow-burning saxophone and clarinet accompaniment recalls the European jazz of Waits’ Alice album. Okay, so it’s not an album you’re likely to play with every bowl of cornflakes, but it’s one that will haunt you for days whenever you do. Like those French films, you might come away from Wit’s End feeling like you’ve witnessed a masterpiece, but you’ll have a pretty hard time explaining why.