The first words of this scattered, turbulent, engrossing collection are significant. "I fancy myself a poet today," Cass McCombs sings on ‘I Cannot Lie’. He has long had a certain preoccupation with poetry, and anyone who has followed his artistic trajectory since his 2003 debut A will have noticed his lyrical experimenting with imagery, narrative and his oblique form of confession.

On this new record, made up of rare and unreleased songs since A, further poetry references appear with ‘Poet’s Day’ (even if the Urban Dictionary definition of this phrase is rather less than refined), while on Big Wheel And Others (2013) he snarls about "shitty poems" in ‘Morning Star’. Poets appear again in ‘Sooner Cheat Death Than Fool Love’ from the same album. He has also actually published his own poetry through Vice.

However, McCombs’ attitude to poetry, if the line from ‘I Cannot Lie’ and ‘Poet’s Day’ is anything to go by, is often heavy with irony and sarcasm. This complicated dynamic may reflect his own famous reticence to embrace the myth of the artist, with his shunning of interviews and distinct lack of image. McCombs does acknowledge the impulse towards expression and a need to produce art, yet he also displays a stark discomfort with the egoic implications of this, with the suggestion he is somehow elevated, hence his suspicion of his persona as poet.

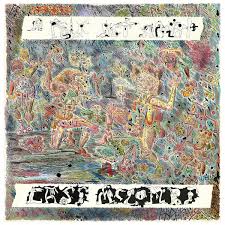

I say all this because the most striking aspect of A Folk Set Apart is its words. The press release describes the album as an "alternate retelling" of McCombs’ oeuvre, and while the song styles are diverse and without fail catchy, the strongest afterglow upon listening to these 19 songs comes from the emotional, brutal, fantastical and indeed poetic nature of the lyrics, which do document the full range of his concerns from down the years. His warped love song is represented by ‘If You Loved Me Before?’, while several tracks exhibit his stream-of-consciousness Americana. Spoken-word appears on the remarkable ‘Texas’, a piece which suggests the less joyous flipside of Van Dyke Parks’ vision of the psychedelic Western on Smile.

There is also politics. The 2012 track ‘Bradley Manning’ stands as his most direct song ever. Basing the song on a Guardian profile of Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning, the track is a sympathetic biography of the ‘whistleblower’, who is currently serving a 35-year sentence. The song follows the same philosophy that Neil Young adhered to on his largely forgotten 2005 album of protest, Living With War, that is, music and melody are an irrelevance, serving only as a vehicle for the message. Young appropriated existing melodies or composed absurdly basic ones – on ‘Bradley Manning’, McCombs similarly employs an unadorned refrain that is repeated as a verse throughout the four-minute track. Prioritising rhetoric over music means that occasionally the words have to be hurried to fit the tune: ‘Bradley Manning’ is not a harmonious listen. Yet the fact certain lines sound shoehorned in only adds to the song’s general defiance, which is encapsulated in the closing line: "Bradley know you have friends, though you’re locked in there".

Though the words do dominate on A Folk Set Apart, it would be impossible for him to release anything that wasn’t awash with delicious melodies. And indeed, there are three songs here that are the harmonic equal of anything he has done. ‘Twins’, for example, from 2009, is simply a very beautiful song, complete with some typically inexact vocal harmonies and mesmerising chord changes. However, again it is the lyrics that transport. As esoteric a first line as "We enter the tomb of Queen Nefertari" gives way to a chorus that is simply, bluntly, "You lied to me". Juxtaposing particularly idiosyncratic or obscure lines with something so universal can be regarded as a staple McCombs trick.

Another fascinating track among the gentler inclusions is ‘Empty Promises’, a sleepy but eerie ballad. The most enjoyable track must, however, be ‘Evangeline’. Recorded in 2014, this is among the most recent songs on the album, and is so bouncy as to veer towards the power-pop of Brendan Benson. It’s the only example of this more radio-friendly style; a whole album of it would be trying, but a blast of feel-good indie makes for another endearing string to McCombs’ bow.

Cass McCombs is often described as being ‘prolific’. And while there has never been a long hiatus between albums, seven albums in 13 years (not including A Folk Set Apart) does not actually make him all that fertile. So any complaints that he releases too much or that these songs, many of which sound like demos, are best left uncollated, are not really valid. For such an enigmatic artist the tracks that don’t make studio albums, are recorded on a spontaneous whim or end up as B-sides, become crucial in furthering an understanding of his sensibilities.

Usually such an album would never be the place to start for a newcomer to the act in question, yet so comprehensively does this explore McCombs’ multiple directions, there is a case to be made that A Folk Set Apart could be a suitable primer.

<div class="fb-comments" data-href="http://thequietus.com/articles/19435-fleetwood-mac-tusk-deluxe-edition-review” data-width="550">