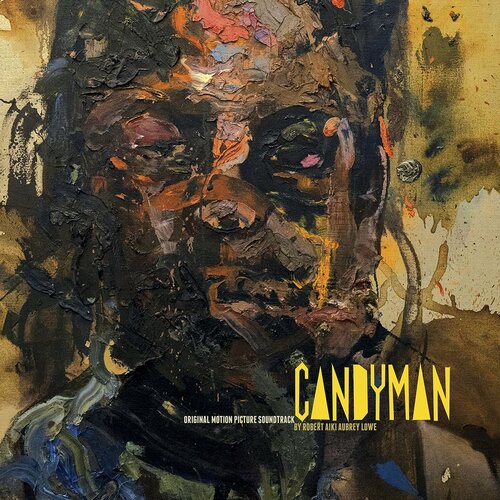

Every generation has its boogeyman, and for many people, especially black audiences in the US, it was Candyman. A ghoul who haunted the projects as a vengeful spirit after being tortured and murdered because he was a black man who fell in love with a white woman, he first emerged in Bernard Rose’s 1992 slasher, based on the book The Forbidden by Clive Barker, and now has returned thanks to director Nia DaCosta and producer Jordan Peele. Scoring the film is Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe AKA Lichens, not only a respected artist but also a previous collaborator of the late Jóhann Jóhannsson on films such as Arrival and Sicario.

The original Candyman had a score by Philip Glass, which came as something of a shock. A celebrated avant-garde composer making music for a genre still seen by many today as exploitative garbage? Outrageous. But it made sense, as Candyman was a well-realised and conceptually intriguing picture about race and the mythmaking of America and its past. In tune with that, and how DiCosta and Peele are now looking at the story from a black perspective, Lowe and his exploratory sensibilities are the perfect match for Candyman circa 2021.

Indeed, what Lowe has created is a frightening tapestry of sound that is as fascinating as it is intricate. What’s interesting about Candyman is that it affords equal space to colour and texture that it does rhythm and melody, with Lowe picking out sounds and ideas, and using those as a thematic base, almost like a leitmotif for the damned. Especially curious is the way he treats many of those sounds electronically, twisting and torturing them until they appear to be drawn from Daniel Robitaille himself (the original identity of Candyman).

Lowe also recognises the mythic nature of the original film and Glass’ score and uses that as a gateway into this new Candyman. Rose’s film has that memorable opening title sequence as the camera glides over the freeways with Glass using choral vocals as a rhythm section, overlaid on an organ melody creating that whole neo-gothic vibe, and Lowe plays into this, using vocal samples and synths to simulate that atmosphere without feeling like it’s a direct recreation. However, he does bring back Glass’ ‘Music Box’ melody in a more restrained and treated form, which succeeds in pinning this as his own, using his own sensibilities on Glass’ theme and letting it be eventually drowned out by industrial noise.

Conceptually, much of the score pays heed to Robitaille’s heritage as the son of a slave and the historical events that come with that, with a mosaic of sounds that echo those experiences. What Lowe does is not necessarily recontextualise but instead repositions them and their intent. In particular, the use of heavy drums that are symbolic of reclaiming African culture in times of slavery and at New Orleans’ Congo Square, something that drives much of the tension in the score.

The opening track, ‘Prologue’, is Lowe’s mission statement, with haunting spectral vocals modulating into foreboding low string lines, where you can hear the voices clawing at the base melody. Glass’ material enters as a kind of reckoner early in the record, but it’s ‘Row Houses’ that really illustrates what Lowe is bringing to the table, with these huge portentous drones that feel like the wooden panels on a ship creaking outwards and a presence of swarming strings – in the original film, Robitaille was eventually killed by thousands of bee stings. Lowe is holding his cards close though, and the first few cues have a sickening feeling of foreboding running through them.

Snippets of Glass show up in ‘Rows and Towers’, but it’s the overlay of what sound like snippets of voices that are crying for help that really amps the tension, with the snatches sounding like they were recorded underwater, gasping for air perhaps. The effect is incredibly claustrophobic and it’s a place Lowe is happy to leave us in, with a perpetual state of dissonance and impatience. This isn’t helped by the incessant metallic grinding in ‘Joke Summoning’ that is reminiscent of Wayne Bell and Tobe Hooper’s musique concrète score in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

That same feeling of anarchic cacophony infuses ‘End of Clive and Jerrica’ and it gets quite unbearable, with Lowe refusing to pull back from assaulting the listener, but it’s in ‘Brianna Finds Bodies’ when things begin to tighten up with an ingenious synth riff that echoes African drum patterns. The drums weave in and out of cues like a shark fin breaking the water’s surface, with ‘Elevator’ mixing them with several piercing tones that end up like sirens before it all takes a left turn in ‘The Story of Daniel Robitaille’, which creates a thoroughly disturbing atmosphere through droning with just a hint of melancholy before it’s interrupted by sparse music box hues full of memory. Lowe uses music narratively here so subtly it could almost be missed, with the colours changing so slowly, but so beautifully, as it almost seeps into ambient territory.

One of the best things – or worse if you’re terrified at this point – is the way Lowe’s pace is almost methodical, painfully drawing out sounds and making them needle at you. You’re trying to pick out points where you think it’s going to get intense, but it’s like being at the dentist, where they tell you that it’ll all be over in the blink of an eye but to you, it feels like you’ve been in the chair for three days. And that’s a good thing because you have no choice but to just sit there and listen and let it take you.

‘Leaves A Stain’ is a pure example of this, where an ethereal vocal is drawn out into a tortured scream of sorts, and it’s beautifully haunting and unbearable at the same time, which is really Lowe’s throughline. But what’s interesting is how he uses his sounds in a way that’s rather like Philip Glass; there are a lot of scores, particularly in horror, that go for a blend of sound design and music and as a result tend to feel less unique. But Candyman is beautifully methodic in the way Lowe layers those sounds and looks at their relationship to each other while letting the subtext remain subtext, which some others might put at the forefront.

It’s always a challenge to talk about a score to a horror movie when you haven’t seen the film, but the varied layers of Candyman make it fascinating to listen to. Yes, it’s terrifying, but it’s also beautiful and sad and challenging. And I look forward to being challenged further by Lowe, and by this score.