It has now been 40 years since the formation of Cabaret Voltaire, one of Sheffield’s single most enduring contributions to music worldwide, and, in both a musical and cultural perspective, it seems a fitting time to revisit their work. In the polarised era that they existed in for the first decade of their career, with the transition from Britain’s grim economic decline in the 70s to the false promises of the beginnings of New Liberalism in the early 80s, a highly-charged political climate caused many decisions by artists and most everyone else to be implicitly interpreted as politically weighted. Starting as they did on Rough Trade, an organisation who enthusiastically dirtied their hands in the movements of the times, it would have been difficult for the Cabs to avoid these currents, and if the lyrical content of their material seemed to dodge direct references to contemporary events, it was hard to ignore the revolutionary sound of the group, which quickly earned them the ire of punks and their successors and cast the group perpetually on the fringes of popular music.

This is an odd fate for a band whose music could easily be said to have made outright overtures to the very scenes that spewed vitriol back at them. Although the more abstract and noise-derived pieces clearly ruffled feathers, the borrowing from sounds of the time such as reggae and dub, and even a few punky numbers (‘Nag Nag Nag’), clearly show the Cabs were attempting to be somewhat accessible in their wanderings. The independent music scene in Britain was thriving at the time and earning its fair share of hits, but their strangeness, obsessive use of American preachers as lyrical content, and repeated references to fascism all made them a bit too far out to attract chart success.

It also earned them the rejection of the rapidly growing indie fan base, who were quickly becoming the new mainstream in the emerging music scene, but were losing their more radical notions with the transformation. Eventually, Cabaret Voltaire simply did what many a frustrated independent band did, and seeing major label interest in electronic, dance-oriented music growing, opportunistically signed to Virgin in 1983, all without really changing their musical outlook much. This further alienated independent music fans but also, rather contradictorily, earned them their biggest selling records, and the end of the decade found them aligning themselves with American house music before the members eventually took separate paths that continued to influence future developments.

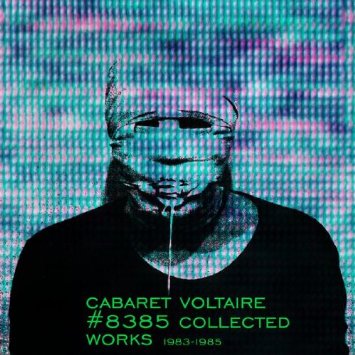

In the longer term, what the brief and underrated visitation to the majors did was cause their albums of this era to be criminally under-heard by later generations. Critics of the time dismissed them as commercial capitulations, and they quickly disappeared from circulation to remain mostly gone for almost three decades, while earlier material remained available and celebrated. Eventually, a lopsided consensus emerged that was more the product of the polarised times than a neutral evaluation of these works. Large labels are rarely kind to those with limited profit-making potential, and by decade’s end Cabaret Voltaire had essentially ceased to exist as Stephen Mallinder relocated to Australia and Richard H Kirk’s succession of pseudonyms and projects took him deeper into techno, with the seminal Sweet Exorcist releases anchoring the very earliest of Warp’s catalog.

Now, with industrial music in general and industrially-inclined techno back in an uproar for the past few years, Mute’s reissue campaign comes at an opportune time. Culturally, it also comes at a significant juncture; after 30 years that saw the rise and collapse of New Liberalism in Europe and the States, contemporary outlook for common citizens not of the moneyed classes is especially bleak, and indeed some greater parallels to the late 70s are visible given analysis. At the same time, the judgments of music critics made 30 years ago are also starting to fade, and it is now possible to revisit this music in a fairer context.

Apart from a single, overlooked Virgin reissue around 2000 and scattered compilations, most of the music here hasn’t been available almost since it was initially released, and certainly The Crackdown alone will serve to change some opinions of the Cabs’ tenure in the majors. Indeed, if the record takes a step back from the sprawling experimental tracks of 2×45 or Three Mantras, it does so by harking back to the shorter song lengths of their earlier albums. The dub influence is back to the fore, as are weird, tinny reggae horns, both of the synthesised and acoustic variety. The production is noticeably cleaner than their underfinanced independent recordings, but it’s hardly less dark, and the added clarity serves to show off the diverse, layered productions, which draw equally from dub, funk, and early electro. Mallinder’s vocals are easier to cipher than they had been before, but the pop tones they would later take on are evident on a few tracks from the album: the title track, ‘Taking Time’, ‘Animation’ and the cynically comical ‘Why Kill Time (When You Can Kill Yourself)’. Much of the rest would not sound out of place on Red Mecca, but benefits from more transparent production, while the lyrical themes remain as fragmented and inscrutably bleak as ever. The album’s second half mostly finds them sounding very recognisably like their earlier selves, especially the closing trio of sinister nearly-ambient works and prominent swaths of horns by Kirk.

By next year’s Micro-Phonies, the gap between this and their earlier, independent music becomes clearer. ‘Do Right’ uses keyboards more overtly melodic, and the funk of its backbone is less choppy and fragmented than it was before, with the beat moving close to a straight 4/4 pulse. For a band who had referenced reggae so many times previously, ‘Digital Rasta’ seems overly obvious, although its dub-influenced production was extremely sophisticated for the time; ‘James Brown’ channels another of their fundamental influences in a similarly conflicted manner. The pop-leaning vocal approach now dominates even if songs evade easy interpretations. It ends in the famous single ‘Sensoria’, a curiously light dancefloor track about overstimulation and addiction in the modern age. Throughout, the innate weirdness and jumpiness of their rhythmic approach is dialled back and the sequencer melodies more obvious than before; the result may be more unified and the combination of elements still distinctly Cabaret Voltaire, but the sharper edges have started to fade in favour of the sleekest dance sound they would ever achieve.

Going back to their obsessions with American oddities, The Covenant, The Sword, And The Arm Of The Lord references American political extremism in its title and American music in its substance. It’s a pacier, funkier album than the 1984 effort, but it also it more abrasive and strange and holds together better, even if it lacks obvious singles. The squalling electronics, metallic sheets of noise, and Eastern influences of ‘Whip Blow’ hark back to earlier triumphs, but it ends unremarkably one track later. It’s case of a band revisiting past themes in a toned-down manner, but overall the record feels like an indecisive combination of their classic sound with the newer dance leanings.

For the remaining material, collectors are well taken care of with a “lost” but partially-released soundtrack to Earthshaker, about half of which are alternate versions of album or single tracks; the remainder is a series of numbered but interesting instrumentals very much in the style the other music in the box. Also included is a DVD of two live performances from 1984, and more DVD material of experimental video footage featuring songs found on the box but whose videos were previously only on VHS. Of greater general interest to listeners are the two discs of extended 12” mixes and Drinking Gasoline, both of which showcase The Cabs on extended dancefloor versions and give more room for experimentation than the shorter album tracks. Par for the course for 80s disco mixes, the extended versions are mostly radical reworks whose choppy editing and extended instrumental sections erase the more pop-leaning structures they were starting to use in favour of freeform, beat-based sonic experimentation. No other credits are given, so it is safe to assume the sometimes maddeningly twisted works are the band’s own, and they go some way to making up the distance between the poppier later tracks and their earlier collage-esque efforts. Alongside The Crackdown, these extended mixes mark one of the real highlights of the collection and illustrate the essential link between Cabaret Voltaire and later dancefloor sounds.

If the continuing relevance of this material was never seriously in doubt, in resurrecting a swath of the Cabs material that had unfairly languished in obscurity for far too long, Mute have done a service in recovering an important transitional period for the group and for dance music in general. Sheffield would continue to be an important center for electronic experiments in decades to come, and this music more than most others illustrates a sophisticated blend of pop elements and diverse rhythmic influences that far outlasted the initial noisy outbursts of late 70s industrial music. Now, with the 90s pop-industrial movement fading into the background, it is refreshing to see record labels taking chances and reviving a once-stigmatized genre, and the current crop of bands exploring these sounds contains some of the most promising new music heard in some time. Cultural parallels considered, it could be that, like their 70s and 80s predecessors, their intense statements concerning the state of society may do little to change the status quo. That said, the leaden-handed interpretation some of industrial music’s current talents take is only a small part of the sound, and there is still much to be learned from Cabaret Voltaire’s diverse, agile, and quick-footed work from this era.