Finally back out on vinyl, and restored lovingly via the means of half-speed mastering and all that, these four albums represent the essence of Brian Eno. A brace of releases that helped push rock music into new forms, introduced new influences and refreshed the ideas of how you go about making it.

Surrounding himself with a crack team of collaborators on Here Come The Warm Jets – Robert Fripp, Simon King of Hawkwind, Chris Spedding and all of the Roxys bar Ferry – Eno pitted them against one another in order to capture ‘catchy accidents’, seeing how a new dialogue can be formed by competing musicians. He would also act out movements or instructions to the musicians, and with production – the ‘studio as instrument’ – managed to bend things out of shape to a point where they bore no resemblance to what had been played.

Opener ‘Needle In The Camel’s Eye’ strafes into being like a metallic assault foreshadowing My Bloody Valentine by a good decade or so, with Eno’s multi-tracked voice – credited to Nick Kool & the Koolaids – as a chiming invasion. It manages to sound like the past and the future. The title track’s actual warm jets – not named after any fruity watersports – refer to the fuzzy warm flow of treated guitars. ‘The Paw Paw Negro Blowtorch’ singlehandedly invents Talking Heads. The grandiose outer-space wall of sound created by voice and treated piano of ‘On Some Faraway Beach’ still illuminates new melodies and dimension each time it’s played, 40-odd years after release.

With Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy, released 11 months after Warm Jets, Eno had taken to using the Oblique Strategies cards he’d created with artist and sleeve designer Peter Schmidt during the recording process, this time with a core band featuring Phil Manzanera and Robert Wyatt and a smaller list of guests including Phil Collins, Andy McKay and the Portsmouth Sinfonia. The sound had refined into conventionality as Eno tickled song structure into a more instantly accessible whole with less attack than before. ‘Mother Whale Eyeless’, ‘Put A Straw Under Baby’ and the astonishing pre-punk ‘Third Uncle’ as particular highlights.

By contrast, 1975’s Another Green World is much calmer, with the avant smoothed into a new pastoral ambient pop and Eno singing on only five of its 14 tracks. Inspired by the likes of Fluxus, Eno decided to have no ideas beforehand (itself a plan of sorts). The making-it-up-as-he-went-along paid off. And while there was no shortage of guest musicians, such as Robert Fripp, Phil Collins and John Cale, on seven of the tracks Eno played every instrument. If you want to see where all strands of Eno cross over, this is the album. It’s a proper masterpiece.

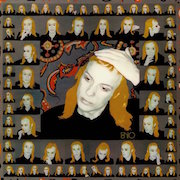

By the time of 1977’s Before And After Science, Eno had begun making his forays into – or even inventing – ambient music with Music For Films and Discreet Music, as well as collaborating with Cluster on the Cluster & Eno album. Rather than book a studio and knock out an album in a fortnight as he’d done previously, Eno took his time putting Before And After Science together, adding Can’s Jaki Liebezeit, Henry Cow’s Fred Frith, Fairport Convention’s Dave Mattacks and his Cluster chums Möbi Moebius and Achim Roedelius into the mix. The songs capture a mixture of gentle nihilism and joy, sensing an ending but offering escape at the same time. A euphoric melancholy. It’s no wonder LCD Soundsystem have based their career on ‘No One Receiving’.

These albums spark off new musical roads and forms of transport, harnessed through new methods and forms of thinking, but there’s a melodic sensibility embedded throughout. They effectively provided a whole new approach. The five-year span of productivity is unrivalled with at least seven albums and his various production credits – he certainly wasn’t fucking about. He’d experimented with the modern pop form and created several new paths for countless others to follow, and now Eno’s work, at least as a pop performer himself, was done.