There’s something peculiar in the wave forms on Benjamin Tassie’s A Ladder is Not the Only Kind of Time. Opener ‘Walkley Bank Tilt’ starts with a low, even line. It continues uninterrupted, before a vertiginous rise into uneven terrain. Other pieces take different paths. ‘Swallow Wheel’ is persistently jagged, as though you’re looking at a heart monitor. It jolts into a steep incline, then an elegant rise and fall. Like a gentle, single swish of a brush on a canvass.

This might sound like graphics appreciation rather than a music review, but the undulations on the Dropbox visualizer through which I’ve been listening to this record are perplexing. Water’s flow is constant, unignorable in Tassie’s music, yet it seems downplayed. ‘Walkley Bank Tilt’ begins with a gush of unaccompanied river which seems understated when shown graphically. ‘Swallow Wheel’ starts with a foreboding drone and haphazard plucks of a water-propelled harpsichord. Yet they sound so delicate compared to the splashing river that their presence looks over-represented in the pointy wave form.

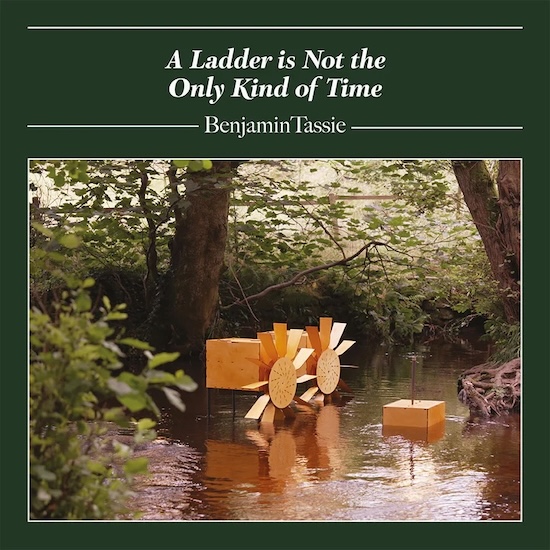

The album was recorded in the Rivelin Valley in Sheffield, an area marked by the ruins of twenty watermills and twenty-one dams. Tassie worked with water-powered instruments built in collaboration with Sam Underwood. The aforementioned river-powered harpsichord, a hurdy gurdy activated by a water wheel rubbing a rosined wheel against two strings, and the Hydraulis, a kind of organ where water displaces air, the pipes sounded by submerging the instrument.

Each track is a single take from the site of a derelict mill. Sometimes, Tassie was accompanied by Rebecca Lee on the Renaissance bass viol, and Robert Bental on Nyckelharpa, an ancient Swedish stringed instrument. The album collects lulling compositions which feel more about continuity than eventfulness, a series of texturally rich drift states at odds with the constant stream of the river that underbeds them. Sometimes incidental noise creeps in. Distant voices on ‘Wolf Wheel’. What sounds like one of the instruments beginning to creak on ‘Plonk Wheel’. Elsewhere, traffic hurtling by in the distance.

Just as the visualiser presents the music’s dynamics differently to how they’re heard, Tassie’s compositions unearth hidden eddies and currents in the river. As if the instruments are plotting the paths of different energies and trajectories beneath what, on the surface, seems linear and homogenous. What’s superficially constant becomes multifaceted, layered and filled with nuance when transmuted into sound. In the release notes, Tassie talks about the overlaying temporalities in the Rivelin Valley, decaying industry and the wildlife blossoming in the remains. What these ten tracks end up conveying most concretely is the physicality of the river itself, a landmark equal parts fixed and mutable.