Stop. Wait.

Did you hear that pulse? A soft, single note, somewhere on the edges of hearing.

Stop. Wait.

Now a soft, gentle crackle, both welcoming and unnerving, sending its message to us softly from space.

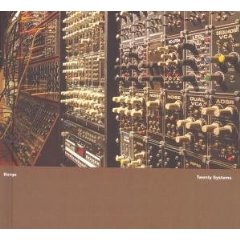

Twenty Systems acts upon us this way. It tells us a story of synthesised sound in miniature, in the movement of waves, in the language of frequencies, in the smallest vibrations. Ben ‘Benge’ Edwards, the electronic composer, record label owner and synthesiser collector, is our trusted narrator. He tells us his story in twenty short chapters, making twenty tracks on twenty synthesisers from the twenty years between 1968 to 1987. Brian Eno has called the result "a brilliant contribution to the archaeology of electronic music". I’d also call it a strange, aural history, or a broad, wild and rangy roman-a-clef.

In 2008, we need Twenty Systems more than ever. For today, we experience the music of the past in fragments and fissures, with little knowledge of how it all links together. We also lap up genres inspired and fed by the synthesiser, whether we are dipping our toes in waters cosmic or radiophonic , or dredging up Krautrock, Italo or electro. And many musicians we admire redeploy their discoveries from these depths on brand new recordings, pausing only to worship their forebears at multicolour-wired memorials.

There is magic in this anarchy, naturally, but there is danger too. After all, the threats of empty reverence and the cold eye of kitsch hang horribly heavy when we think of the synthesiser in history, and the evocative names, looks and sounds of its models. But Benge gives their stories clarity and substance, respect and intelligence. Not only do his album’s wonderful sleeve notes tell us how, when and where his instruments were used, but the music within them reveal how these machines really work.

Benge’s album takes us from the 1968 Moog Modular to the 1987 Kawai K5M. He lets his machines talk for themselves. No sounds are modulated. No effects, edits or processing techniques are used. By keeping him compositions minimal, Benge’s synthesisers speak to us directly.

When Benge shows us his early models, this is particularly clear. A few notes here, and a few shuddering fissures there, convey terror and innocence in compelling equal measure. The 1969 EMS VCS3 is a particular revelation: notes played in octaves being torn gently apart by metallic waves and chirrupping crevasses. Next comes the 1971 ARP 2600, singing gently over a sinister drone. Then the 1972 Serge Modular follows, spitting, snapping and spurting like an extraterrestrial science laboratory.

Moving through the album’s beguiling chronology, you notice the unique personality of every instrument presented, and how Benge’s performances subtly point out progress. The 1974 Oberheim SEM plays us notes in polyphony. The 1975 Moog Polymoog performs what sounds like West African folk music as rendered by Steve Reich and an orchestra of aliens. The Korgs from the turn of the 1980s present shimmering sounds with more depth, and less edges.

But by the time we reach the final chapters – those far distant lands of 1986 and 1987 – certain cracks have been sealed in the tones, and some harsh creases ironed. This is one of the worst misconceptions about the evolution of popular music: that its progress should not be about making mistakes, or about the anarchy of error doing its damnedest. Benge knows this too, and stretches these final machines to their limits.

Play this album in one sublime, mind-melting sitting, and the moral of Twenty Systems‘ grand narrative becomes blindingly clear: we have all spent the last two decades catching up with our past. Listen to 1985 Yamaha CX5m and hear the strains of Orbital’s ‘Steel Cube Idolatry’, the experiments of Autechre, the distant echo of 2-step. Listen to the 1981 Yamaha CS70M and hear Boards Of Canada and the introspection of post-rock. Even in the 1968 Moog Modular, you can hear the ghosts of minimal techno, and the grand opera of noise.

Above all, Twenty Systems is a library of sound given organic form – the veritable huge tree of knowledge. Teaching us so much about the wild roots of our music, it will keep growing, too. With its every wave, frequency and vibration, it will help us to breathe.