If Kate Bush was the most frequent comparison cited in reviews of Natasha Khan’s 2006 debut album Fur And Gold, the debt is equally palpable here. Her preoccupation with medieval, swords and sorcery nomenclature survives undiluted too. Opening track ‘Glass’, vocally a near perfect approximation of latter period Siouxsie, feels like a bookend to debut album curtain-raiser ‘Horse And I’. The lyrics again reconcile rapture in nature and literary fantasy. Emerald cities and knights in crystal armour? It’s as evocative of Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion series as anything Hawkwind ever recorded.

Where Bush was lost in Bronte’s earthy landscapes, Khan draws on more folksy influences; fairytale, allegory and myth, while similarly reliant on elemental imagery. Dave Kosten (Faultline)’s production is as gossamer-spectral as the shimmer of morning sunshine over a woodland copse.

It gets all the more pointy-hatted and magical in ‘Sleep Alone’. Khan weaves spells in the cause of summoning a lover, as trickling water and unfussy percussion provide sonic embellishment. Even when Kahn is singing her head off her delivery seems marvellously cool and controlled, though never completely detached as she glides across her songs as a robust constant. Lead single ‘Daniel’ recalls ‘Last Day Of Our Acquaintance’ Sinead O’Connor (with Stevie Nicks on backing vocals) in its hushed, restrained phrasing. And if it seems like I’m pinning Khan down to female vocal stereotypes (Sioux, O’Connor, Bush, Nicks, Bjork) it’s hard not to note how evocative she is, at turns, of each. To skip the gender-based comparisons for a moment, there are echoes of The Waterboys somewhere in the mix too.

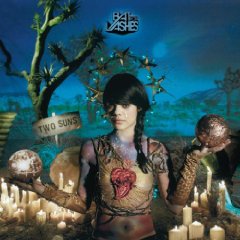

Two Suns, despite the title, is manifestly a nocturnal affair, constantly referencing the fading and return of daylight. Heartache and absence are dominant themes; be it husbands lost at sea (as lest we forget exquisitely explored on Bush’s ‘The Ninth Wave’) or lovers lost to the arms of others. The songs embrace the totality of love rather than hint at emotional nuance. As has been noted, against the backdrop of ‘ordinary girl making sense of the world’ narratives explored by her contemporaries, Khan is a far more ambitious conceptualist. There’s a thirst for magic, for the suspension of disbelief and immersion in dreamscape.

Scott Walker pops in to make a guest appearance on closer ‘The Big Sleep’. It really is a closer too; a literal meditation on death. Halfway through the song the vocals are done with, leaving only a skeletal piano refrain and a faintly disturbing electric hum.

Has she Khan yet really found her own voice as a songwriter? Sometimes a little more bombast might be apposite – the tonal quality of the album, heavy on cello, subdued electronica and wispy piano, is a little too quiescent at times. Although undeniably beguiling in mood, Two Suns can occasionally feel unsubstantial. Yet it’s a broadly impressive album, though not, perhaps, the wholly compelling one Khan will surely one day make.