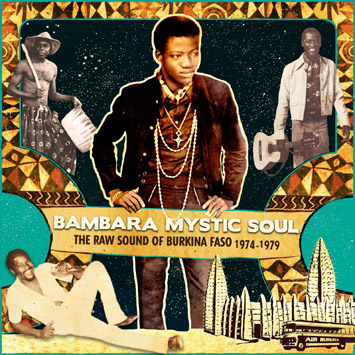

This latest collection from nugget unearthing specialists Analog Africa comes from deep in North Western Africa and features 16 tracks covering the golden age of Burkinabè music. The compilation follows the label’s similar overviews from inspired times in Benin, Togo and Angola, amongst others. Bambara Mystic Soul: The Raw Sound of Burkina Faso 1974-1979 represents perhaps the label’s most underexposed region to date. Burkina Faso has produced very little exported popular music compared to its neighbors or African musical giants like Nigeria and the Ivory Coast. And records that have appeared on Western labels, such as Nonesuch’s Savannah Rhythms and Rhythms of the Grasslands covered more traditional percussive forms, reflecting the music played in the rural landscape. Although those were recorded around the same period in the early 70s, the musicians on the tracks on Bambara Mystic Soul had travelled beyond the arid Sahel desert. Having absorbed a wide range of influences from across Africa, the sounds they crafted displayed a more cosmopolitan feel.

The record documents a time prior to the military coups in the former French colony that eventually led to the then Republic of Upper Volta, or Haute Volta, being renamed Burkina Faso (“the land of incorruptible/upright men”) in 1984. The groups showcased here were influenced by sounds coming from neighbouring countries like Ghana, Ivory Coast and Nigeria, during the height of the Afrobeat revolution.

The impact of the music is immediate, and the sound timeless, as Amadou Ballaké et l’Orchestre Super Volta kick in with ‘Bar Konou Mousso’, laced with jazzy saxophone breaks and loose but punctual guitar lines. The lyrics reflecting on Ballaké’s experiences as a musician playing in bars every night: “If you’re musician, you’re no one, my house is not paid, at the Independence Hotel, with the white man, It’s 5,000 Francs". A prominent figure during this period, now regarded as a national icon, vocalist Ballaké led several pioneering orchestras from the capital Ouagadougou, and features on six tracks, variously accompanied here by Les 5 Consuls and l’Orchestre Super Volta. His career had begun outside Burkina Faso in the 60s in the night clubs of Bamako, Mali, as, like many other Burkinabè musicians, he sought better gig opportunities. This in turn led to the incorporation of wider and distinctive musical influences, like the guitar techniques and Mandingue melodies from Mali and Guinea, just one example of the wide breadth of ideas picked up from other African countries that helped inspire this rich blend of soul.

Existing in the dry savannah plains in hot Sahel climes, regularly facing drought, Voltaics would head to the neighbouring Ivory Coast to seek employment. Similarly, the country did not host adequate studio facilities, and many of these recordings were made outside of Burkina Faso. While visiting these studios the musicians made good use of their neighbours’ studio knowledge. The musicians were also aided by the post-independence urban middle class, who were willing to invest in the Burkinabè arts, which included releasing the music. Labels emerged like Volta Discobel and Club Voltaique du Disque (CVD) to document the sounds for people at home, originally releasing many of the tracks included here. The recordings have a warm sound, and include a combination of traditional Islamic rhythms, as on Orchestre CVD’s ‘Rog Mik Africa’, and a hint of Afro-Latin sounds introduced by visiting Cuban groups, featured on Mangue Konde et Le Super Mandé’s ‘Kabendo’. And where there is perhaps a bit of tape wobble, on Amadou Ballaké et Les 5 Consuls’ ‘Renouveau’, and certain l’Orchestre Super Volta tracks, it adds a fitting haunting quality to the 35-year-old sounds.

Taking the soul blueprint of Ballaké’s music, his younger contemporaries at this time followed with the additional influence of 70s Afropop and funk. Abdoulaye Cissé’s ‘Kodjougou’ begins on a stomping riff like a more energised take on Bob Marley’s 1973 ‘Get Up, Stand Up’, with added psyche fuzz guitar soloing, rapid-fire trap work and menacingly urgent vocals, while the playful wah-funk of Compaoré Issouf’s ‘Dambakale’, oozes a loose sensual swing, as the gently strained lead vocal is backed by a group of female singers on the knee-tremblingly seductive chorus. Mamo Lagbema’s ‘Love, Music and Dance’ revels in a fun Zappa-like wildness. And an undeniably James Brown-styled wail leads into the shoulder shaking shimmy of Afro Soul System’s ‘Tink Tank’, like Fela Kuti, using Pidgin English so the message could be understood by a wider multilingual audience, as the music builds up layer upon layer of polyrhythmic interplay to the endless heavy groove.

The re-discovery of these timeless “raw sounds” offers a tantalising glimpse into this vibrant scene, and a wider exploration into the back catalogues of the artists on Bambara Mystic Soul would certainly be welcome. It will be interesting to see what treats Analog Africa has in store next. For now, surrendering to the magic of this potent African mix as it casts a spell on the soul is just fine.