Every album is a concept album. Or, make that, every worthwhile album is a concept album. While the idea is sullied by its association with otiose sword-and-sorcery nonsense on ice, it becomes more critically appealing if its similarities with conceptual art are brought to light; that is, if one comes to see conceptuality as a governing principle rather than as a tendency towards pseudo-literary bombast. On these improved terms, Never Mind the Bollocks is a concept album. In Utero is a concept album. 36 Chambers? Definitely a concept album. More Songs About Buildings And Food? A concept album about conceptuality itself. They’re ubiquitous, see?

Even if the field is narrowed to those artists who are, you’d assume, self-consciously producing concept albums, there are still many impressive candidates. Liars wrested the form back emphatically from Wakemanism with their laudably odd 2004 witch-hunt They Were Wrong, So We Drowned, but former Auteur Luke Haines is probably the doyen of modern, well, Conceptism. His 2011 album 9 ½ Psychedelic Meditations On British Wrestling Of The 1970s And Early ’80s belied its (knowingly) unpromising title to deliver a spooked exploration of the beige minutiae of a 70s childhood that fused the anti-nostalgia of David Peace’s novels with a homage to an imagined British DIY acid rock scene. To some, it was a stealth success that seemed to come from nowhere.

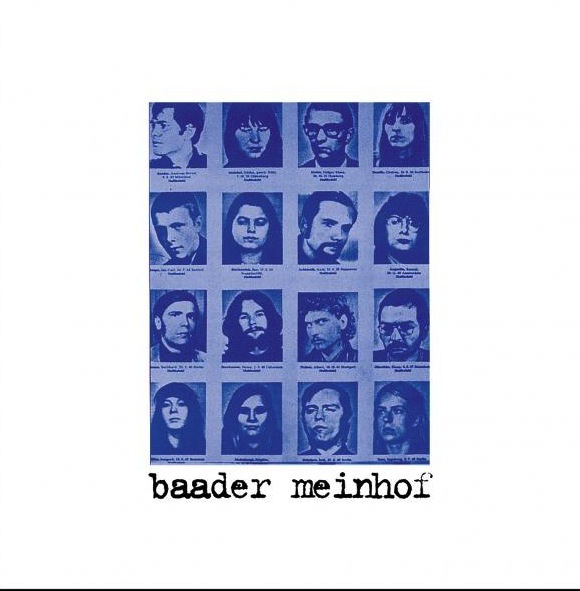

But Haines had already wielded the suggestive currency of the 70s for an earlier, weirder project. Baader Meinhof – released in 1996 under the same name – was, and it’s hard to write this with a straight face, a psych rock-cum-white funk retelling of the story of the Rote Armee Fraktion (Red Army Faction), the radically left-wing German terrorist group who launched a quixotic, but bloody, insurrection against the European bourgeoisie throughout the decade. More so than The Auteurs at their very best, more so even than the gorgeous first two Black Box Recorder albums, Baader Meinhof has a strong claim to being the best thing Haines has ever put his name to.

Why? Well, for a start it’s the closest Haines has come to a distillation of his own perversity. He is obsessed with violence, both in its literal and symbolic manifestations. Whether it’s the valet-turned-murderer who narrates the opening song on the first Auteurs album New Wave, or the liver sausage sandwiches which repulse on 9 ½ Psychedelic Manifestations, his vision is mesmerised by aggression and the dynamics of power. On Baader Meinhof, we’re confronted with a particular component of violence, namely its ineffably seductive properties; given Haines’ fascination with the topic, the record is a working-out, an autoanalysis.

Take the opiated, oozy, Cameoesque slope of ‘Meet Me At The Airport’, which lifts the lid on the appeal of the Baader Meinhofs’ 70s quiddity, the Venn space in which nihilistic bellicosity, political idealism and fuckability interlock. "It’s not for God’s love/ it’s not for cocaine", we’re told, but, pointedly, there’s no specification of what it is for.

This is an album which simultaneously identifies with the extremity of the R.A.F.’s politics and unmasks those politics as adventurist posturing. A contradiction, surely, but one in which Haines is able to locate value. It’s an increasingly common analysis that the left have failed to capture desire in the twenty-first century, that the success of the right is down to an ability to, for want of a better phrase, turn the public on. For all their value, social democratic intentions have a brown-breaded worthiness: by contrast, for all its wrongheadedness, the excess-inclined leftist terror of the 70s possessed a beguiling eroticism. This is an album which wants to understand something about the awkward relationship between politics and desire, a relationship we’d do very well to think about in greater detail in 2014.

It’s also brilliantly evocative. Much has been said in the last decade about the capacity of acts like Boards Of Canada or the various Ghost Box projects to push our Proustian buttons, but Haines was already working along these lines in the 90s. It’s not unique to this album, as the nostalgic value of the fragment was something that came up again and again on Auteurs records, but Baader Meinhof has a canny awareness for how the tiniest passage of sound or the most offhanded allusion to geography can open the door on a topography of conflicted memory. ‘Mogadishu’, about the hijacking of a Lufthansa flight by Palestinian operatives working to free R.A.F. members from German jails – solidarity was taken seriously in the 70s – uses one toponym to conjure the entire cartography of postwar militancy and paranoia. Following on, ‘Theme from Burn Warehouse Burn’ opens with snooping, jazzy bass that recalls the soundtrack of a Godard film, before Haines’ rasped incitatives cut in over the top, announcing that "there’s no manifesto/ there’s no formal plan".

Of course there isn’t: that would be boring, and Baader Meinhof goes to quite extraordinary lengths not to slip into dullness. Its mix of homemade funk, politics and metapolitics looks irreconcilable on paper, a project driven by absolutely counterintuitive principles. Yet it’s this apparent awkwardness which makes it work. The funk has a Brechtian function, working as an alienation effect to prevent us from taking the lyrics for granted and, perhaps more importantly, to highlight the utter strangeness of 70s radicalism when viewed retrospectively from the anodyne 90s. What we’re to understand here is how politics might fire the imagination, a point Haines is determined to make, however odd its mode of expression need be. This is a calling-card – perhaps there is a manifesto after all – for pop-as-weirdness, and for the fusion of politics and entertainment.