Much of the passionate rhetoric surrounding The Antlers’ affecting Hospice featured the keyword ‘bleeding’, not only referring to the crackling artery of distortion that flowed through the album, but more specifically lyricist Peter Silberman’s untrammelled outpouring. While other indie bands prefer to tease out a sense of sadness, Silberman’s investment in that dying child and the impossibility of that child ever growing up, was total. He bled it.

Yet his psychologically piercing narration (he described the cancer as a "bear inside her stomach") wasn’t just sad; it was shamed, atoning and beholden to a tainted romantic ideal, and at times just as much to do with the 21-year-old’s fear of disease; or of love cooling to the sterility of that hospital ward; or conceivably a fear of sex. Emotionally speaking it was a deceptively complex album, the broad-stroked candour harbouring an unnerving ambiguity. By rule of thumb it takes a certain kind of unknowable despair to analogize your failing relationship, brick-for-brick, in the form of a terminally ill child, while managing simultaneously to capture the devastating lie of everlasting love. But more than that, almost like Perfume‘s Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, the New Yorker seemed cursed with a unique receptivity to the stink of everyday, lowly misery; an elaborate empathy for impotent wanting.

The concept could easily have translated as callow self-pity at the expense of a sacred subject matter, a kind of indie Munchausen-by-Proxy. But with a precociously wise soul at the helm, the scenario was borne out in sensitive minutia and with an authorial vividness, which lingered with the fantastically penetrating, visceral resonance of an Ian McEwan novel. This, combined with an emotional variegation at work in nearly every particle of a truly captivating plot-line, made Hospice so very real, and honest, and brave; prompting a mass of commentators to lay palm leaves before the unbearable truth of The Antlers.

Burst Apart, by contrast, is a disappointment. Not because it’s a weak album – it’s frequently beautiful – but because the experience of being overwhelmed is such a hard act to follow. Its effect is cumulative, and ultimately satisfying, but it’s a staggered, slow-release kinda deal. To attempt another bruising concept album would have been opportunistic, and even more unfitting of The Antlers – insincere. That was the story, and it’s been told. But it seems proliferation and eclecticism have come at the expense of a direct hit to the heartstrings. By feeling out a tangled patchwork of styles they’ve produced an accomplished, varied sound, which with a new found compositional sophistication verges on post-rock at times. But they’ve lost a lot of traction by downscaling Silberman’s vocals – often a mere smudge on the mix now, though previously the source of all the rich nuance they could ask for, and the font of their maturity for that matter. The feeling is that they’ve assessed their entry album to be disingenuous folly – gauche and undignified. The result is a far more vague and diffused listen, at odds with the close, heavy profusion of Hospice.

Part of their transition from mopers to gentlemen understaters of poise involves upping their rhythm game; which means more beats, more swing, loops and synthetic drum sounds. You want to get experimental, or throw off your dowdy indie sonics? Then embroidering your sound with rhythm for rhythm’s sake is a sure-fire way of offsetting that enervating wallow, and lends a little edge to proceedings in the process. Take for example the king of the millennial indie weepie – the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ ‘Maps’ – which beat the slump out of doughy balladry with a bashed toughness evermore fitting of modern romance (this stuff hurts, remember). So we have ‘French Exit’ which takes after PB&J’s The Living End with its snub-nosed sub-Saharan bass and muffled kicks – ideal for balmy, after-hours Brooklyn; followed by ‘Parentheses’ which, carried on dub bass and hard-boiled hip hop beats, offers Silberman’s falsetto – a newly operatic affair – as the single remnant of The Antlers as we knew them previously, compounded by a perfectly timed guitar progression which packs real grit. It’s followed by ‘No Widows’, another new look for the band which uses a Bjork-esque loop – a kind of tone-toggling clacking on railway sleepers – to lynchpin Silberman’s twinkling suicide fantasy. And, yes, as advertised they’ve gotten a bit electronic, but not so much that it defines the album (let’s not get carried away here). On that point, unfortunately the tech, whilst atmosphere-building, is a bit inconsequential; a bit besides-the-point. It’s an old tale, really.

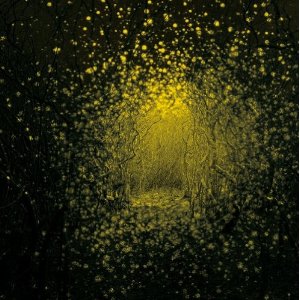

From that point on matters take a turn for the languid and strange, almost as if noir-ish instrumental ‘Tiptoe’, with its muted trumpet and creaking floorboards, is a portal into some Rockwell-ian time warp. Taking inspiration from the leafier end of post-rock, the tactile ‘Hounds’ blows cold sand and spray across the path of a hypnotic three-note phrase and brushed cymbals. The picture is one of peace on a yellowing prairie. Thereafter, preceding the knock-off In Rainbows fare of ‘Every Night My Teeth Are Falling Out’ comes ‘Rolled Together’ which makes gospel from Wilko’s ‘Poor Places’, absorbing that song’s exponential fugue and ticking static in creation of a fluttering, ringing liturgy; much greater in scope than anything appearing on Hospice. As with ‘Corsicana’ later on, bizarrely the band seem displaced from their own music, as if to keep a safe distance from the core statement, which by the end you realise is once again address to a faltering relationship.

So on closer ‘Putting The Dog To Sleep’ it’s time for the truth, which Silberman packages in a typically harrowing metaphor. According to the band it’s their soul track, a last waltz which reframes Silberman’s weary pleas within an old-time setting, somewhere between James Carr’s ‘The Dark End Of The Street’ and The Walkmen’s disillusioned torch album You & Me. Over mournful organs, he begs "Well prove to me / I’m not gonna die alone / unstitch that shit I’ve sown / to close up the hole / that tore through my skin". You can practically hear the sutures popping with every glancing stab of guitar, only this time, after an album of pastel-coloured equanimity, the blood is much redder.