Dance music is a hard thing to write about. In many ways, the nature of the style – its eternal variety of thumping kicks, rattling high-hats and swelling synths – opposes general notions of narrative and criticism, ones generally rooted in sharp, detail-oriented attempts at the seemingly endless, overarching explanations of art. Where dance music explodes, barraging clubs with dark grooves and infinite immediacy, narrative soberly seeks to unpack the mystery of devices themselves, attaching sounds (many of which critics, who often aren’t asked to be producers themselves, can only grasp at in words) to colourful diction, astute references, and messy, inaccurate metaphor. In many ways, critics are asked to analyse the cultural context of a work beyond sound itself, narrating careers and artistic trajectories, connecting allegedly similar intentions between artists, and grasping at the thunderous roar of the club with only their own experiences – often limited to info fed from press releases, bureaucratic intentions from bloated media organisations, and tough attempts at both the illusion of critical objectivity demanded from readers, and the monetisation policies necessary to keep many media sites afloat.

These policies often leave the biggest outlets for music criticism forced to perpetuate what James Parker and Nicholas Croggon call "reduced listening," – simple, convenient narratives that navigate between a Scylla and Charybdis of faux-objectivity and advertising to provide web criticism to consumers at no additional cost. These modes of "reduced listening" offer a "critical (un)knowing" for which highly-specific, niche knowledge of, say, classic drum machine presets or the basics of production software, would be certainly superfluous. The nature of criticism, then, would ask music writers to perfect these modes of "reduced listening," though often understandably missing an endless wealth of musical detail in the process—information on endless subjects from music production and hardware histories to obscure scales and borrowed melodies, sample origins and sonic devices ad infinitum.

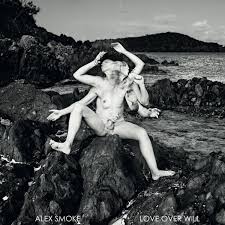

When I sit down to listen to Alex Smoke’s Love Over Will, I don’t want to miss anything. I pull on my dusty Audio-Technica m50s, scratch the clammy sweat off my laptop’s aluminum, and click play on ‘Fair Is Foul’, the first of the album’s thirteen tracks. Released on R&S, the album follows a long string of output for Alex Menzies on labels like Glasgow’s Soma (who put out 2005’s Incommunicado and 2006’s Parabola), Berlin’s Vakant (with 12"s like Hanged Man and F In F) and his own Hum+Haw, as well hip-hop production with MC Non (under the FOOL moniker), and a classical film score with the Scottish Ensemble orchestra. He’s put out releases after release of astute minimal techno, awash with rhythmic deconstructions and burgeoning texture that’s eternally rolling, ringing, and rife with dynamic and melodic variety at every end.

For the first time (as far as I’m aware – re: "critical (un)knowing" above), Menzies uses his own voice. Often it’s a clunky transition from producer to vocalist, and here’s no exception; Menzies voice wobbles in conflict with the metallic flatline of vocoders and pitch correctors, settling deep within the mix, heavily processed and murky in low-register harmony. In contrast to someone like James Blake, another R&S icon known for metallic tones and processed vocals, Menzies’ bellowing voice builds these loose, circular verses, often without much melodic variety, yet interestingly leverage the human voice within song as a static vessel, groundwork as the rest of the track evolves. ‘LossGain’ offers up a good example, with the metallics of Menzies’ processes flaring up over the vocals themselves, blanketing the track in a dark technocratic autonomy. The track ‘Dust’ returns from Menzies’ 2013 single, here marking a familiar breath mid-release before further embarking on uncharted terrain.

As a Glaswegian producer based in Berlin, Menzies’ track title ‘Yearning Mississippi’ strikes me funny. I’m reminded of a time this summer, where, cornered and drunk in Berlin’s Farbrenseher, I listened to an old house veteran ramble on about Chicago vacations – a city he somehow believed to be an eternal, Vegas-style tech-house jungle-gym, one only left to the endless euphoria of club tourists and thrill seekers. Only after visiting did he realise how small scenes with global reach ever actually were, even with ubiquitous documentaries and history books playing them up to unprecedented heights. With each iteration of Chicago house or Mississippi blues, it seems so much is lost forever in the noise, distorted in translation, and played out through records in languages hardly known to even the best linguists. Regions bubble up, icons are exported, and kids born into Glasgow techno find power in the Mississippi croons of Robert Johnson, the state’s hot, sticky sunsets and corrupt political persuasions that sadly persist to this day.

Love Over Will offers a techno release beyond the noise, one that wrestles with vocal placement and layers chaos into algorithms and filtered metrics strung out in evolving time. Where ‘Star At The Summit’s’ metallic hits grow into somber orchestral arrangement, ‘Fall Out’s’ looped music box evolves into 8-bit arpeggios and low-end rumble; the album ebbs and flows, a symbiotic beast between man and machine. The rattling anxiety on ‘Galdr’ succumbs to the uncanny ensemble arrangements and icy synth grievances of ‘Yearning Mississippi’. The track bellows over vocal chants, finally swelling up with the cathartic crackle of well-worn vinyl – at last, the stale, haunting tautology: ashes to ashes, dust to dust.