The revolutionary flames that engulfed Paris in May 1968 – the student rebellions and the worker uprisings and the cultural shifts they initiated in art, music and political theory – spread far beyond Europe. The Vietnam War was at its peak and opposition to it, both in the US and in Europe, was intensifying. 1968 also saw the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King, sparking riots across several major US cities including Washington DC, Chicago and Baltimore, and casting doubt on whether the African-American civil rights struggle could be won solely by peaceful means.

In the midst of all this, a group of New York musicians decided to meet up in Harlem’s Marcus Garvey Park with the idea of forming a band. The date they chose – 19 May – commemorated the assassination three years previously of Malcolm X, spearhead of the more radical wing of the civil rights movement. The choice of this date signalled the political direction that the group, who came to be known as The Last Poets, would pursue over the coming decades. The Last Poets would morph and evolve over time, witnessing several changes of lineup. But all their albums featured incendiary lyrics and an epoch-defining style which combined frenzied spoken-word poetry, jazz and stripped-back percussion – a style that many have argued laid the foundations for hip-hop two decades later.

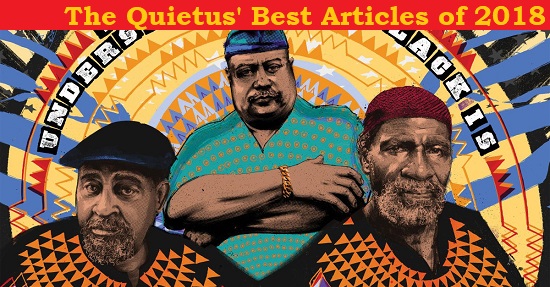

You could be forgiven for thinking that a band whose heyday was the early 1970s would have passed into irrelevance or myth by now. Instead, it’s difficult to overstate the continuing importance of The Last Poets, whose first album in 20 years – Understand What Black Is – has just been released on Studio Rockers, featuring two of the longest-standing members of the group, Umar Bin Hassan and Abiodun Oyowele. Indeed, it’s an indictment of the current political situation in the US that an album such as this still resonates so strongly and that the band’s core messages have hardly changed.

While much of the world watched in shock as a billionaire property mogul, surrounded by various hard-right and white nationalist figures, became the 45th president of the United States in 2016, I doubt it came as much of a surprise to the Poets, who have long been familiar with the repressive powers of the US state. In the 70s they were monitored by the FBI’s CoIntelPro (a counter-insurgency operation designed to infiltrate and disrupt domestic groups deemed political threats to the US government) for their espousal of Black Power politics. The inauguration of Trump seems to have been the catalyst for the group to emerge out of relative obscurity (though they did have plentiful cameos on hip-hop tracks throughout the 90s and 2000s).

‘Rain Of Terror’, at almost 10 minutes long, is an unflinching attack on the self-mythologising of US culture, arguing that violence, conquest and oppression have always been at the heart of American political life: “America is a terrorist / Killing the natives of the land / Killing and stealing has always been a part of America’s masterplan”. This is The Last Poets at their most unapologetically militant, recounting the violence done to Native Americans, the legacies of slavery and segregation and the firebombing by police helicopter of Philadelphia’s MOVE organisation in 1985.

Similar sentiments are voiced on ‘How Many Bullets’, a defiant howl against the assassination of political leaders and the continued institutional violence done to black people in the United States. The track is a simple statement of refusal – “You can’t kill me / You can’t see” – its lyrics underpinned by a fierce rhythm that propels the song ever onward.

While the lyrical content touches on similar themes to earlier work, musically the band has veered entirely towards reggae in place of the minimalist arrangements of their previous albums. It’s a surprising listen at first: the LP calls to mind the dub poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson as much as The Last Poets’ contemporaries Gil-Scott Heron or the Watts Prophets. The tight, punchy dub basslines come courtesy of the studio skills of Brighton-based UK dub and reggae producer Prince Fatty, alongside jazz and funk mastermind Nostalgia 77.

On one level this makes sense: the album draws on the heritage of the equally militant and socially conscious sounds of roots reggae, which voiced the grievances of the Jamaican diaspora in the UK and elsewhere at the same time that funk was speaking truth to power in the US. But it also creates a record that feels strangely stranded in time, a protest album living in the echoes of albums both past and present.

In some ways, it’s is a tough listen: there’s a clear sense that the struggles that began in the 1960s have yet to come to fruition. The track ‘We Must Be Sacred’ speaks to this directly, asking “How far have we come? / How much further do we have to go?” But the group also reveal a more melodic, playful side on tracks such as ‘She Is’ and ‘What I Want to See’.

In fact, running alongside the narrative of unwavering resistance to oppression, the album is imbued with an almost mystical call for human understanding, voiced most poetically on the opening, title track, ‘Understand What Black Is’. Here, the Poets take aim at the way in which the language of race has not only divided human beings, but has also created obstacles to true self-knowledge. Blackness here is to be understood is cosmic terms, as “the source from which all things come / the security blanket for the stars” and as “the light shining on a path / leading to the sun”. It’s a powerful premise, one that weaves its ways through the rest of the record, creating a document not only of struggle, but of transcendence, resilience and hope.