Scott Walker, 30 century Orpheus, returns to the underworld. But this time, he’s come with back-up. Sunn O))): orthodox cavemen, purveyors of solid air, black amps tearing the sky. “Maximum Volume Yields Maximum Results”. Have you ever breathed a frequency?

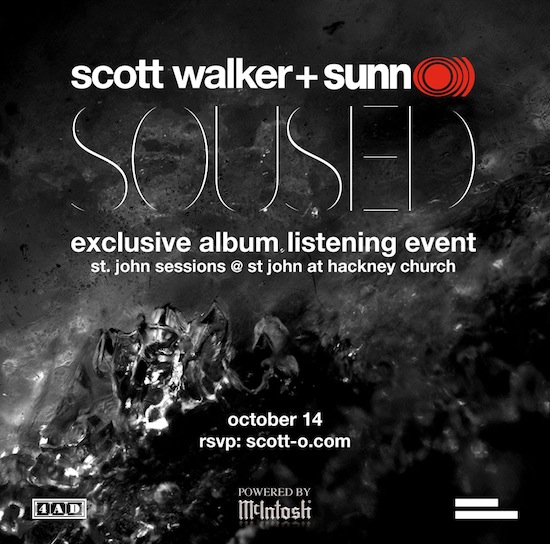

Soused: drenched, pickled, pissed-up. When this collaboration was announced in July, with a publicity photograph showing Stephen O’Malley and Greg Anderson de-cowled alongside Walker, I had questions.

Would Sunn O))) be deployed to cloak Walker’s experimentation in shrouds of noise? When he sang “a sphincters [sic] tooting our tune” on Bish Bosch did it anticipate that Sunn O))) provide the follow-through?

Or was that too obvious? Would they instead take the left-hand path together in the direction Sunn O))) pursued on 2009’s Monoliths & Dimensions, more towards the avant garde, for which they had originally pursued Walker for a vocal contribution? Was it closing track ‘Alice’ that they had in mind for Walker’s voice? It seemed written to join its siblings, ‘Clara’ and ‘Jesse’ from The Drift.

Walker took his time to return their interest, but the reaction to the news of Soused has been feverish. As lugubrious alternative rock band Low noted on Twitter: “The world must be finally ending because the soundtrack is done and ready – Scott Walker with Sunn O))).”

Scott Walker is a specialist in absence. He left over a decade between Tilt and The Drift. He refuses to perform live. When I went to Tilting And Drifting – The Songs of Scott Walker at the Barbican in November 2008, his later repertoire was delivered by the likes of Jarvis Cocker and Damon Albarn. “Please note: Scott Walker will not be performing.”

Instead, he orchestrated from the back of the stalls. Two rows in front of me, a female lookalike in tight cap and dark glasses repeatedly leant forward and twisted her neck back over her shoulder to catch a glimpse of her doppelgänger. This doubling seemed as ostentatious and uncomfortable as The Mystery Man’s first appearance in David Lynch’s Lost Highway.

The pallid and uncanny figure (played by Robert Blake) approaches Bill Pullman’s free jazz saxophonist Fred at a house party. The background music fades to silence: “We’ve met before, haven’t we?” Fred doesn’t think so. The Mystery Man insists they have, at Fred’s house: “…as a matter of fact, I’m there right now.” Fred refuses to believe him: “You’re fucking crazy, man.” The Mystery Man gets out his cell phone: “Call me.” When Fred calls his house phone, on the other end of the line, The Mystery Man answers: “I told you I was here.”

The second time I saw Sunn O))) they weren’t there. They performed at the Maureen Paley Gallery in East London in June 2006 without an audience – artist Banks Violette created a representation of the performance in cast resin and salt, the mighty eponymous amplifiers and all, “to generate a feeling of absence, loss and a phantom of what was”. We were let in to see it afterwards. It’s preserved on their audio record of the event, Oracle.

With these two artists, what makes their music feel sublime can also make it seem ridiculous. There’s a lot of dark humour, a lot of silliness about their work: “That’s a swanky suit” Walker croons suddenly on ‘Cossacks Are’ (opening The Drift); Sunn O))) don’t blanch at calling a song ‘HELL-O)))-WEEN’ (opening White2). Their respective studio shenanigans – punching and slapping a pig carcass, recording vocals in a closed casket − leave them open to derision. But that vulnerability is the starting point for exploration.

They make sparse music with base materials, cinder blocks of sound; in the case of Sunn O))), they distend the sine wave itself. They might be considered pitiless sonic architects. But they are careful to drill down to an emotional truth. This truth is often stark: frequently it is fragile and beautiful, brittle and sharp.

‘Brando’, the first track of Soused, completely wrong-footed me: a shimmering backdrop, Walker opening proceedings with an operatic sweep of the hand – “Ah, the wide Missouri” − and a plaintive, Steve Stevens-esque Top Gun guitar lick courtesy of Tos Nieuwenhuizen (who extends Sunn O))) to a trio and supplies lead guitar on some but not all of the tracks). It is set off against a rudely high-in-the-mix guitar similar to the distorted intrusions on Bish Bosch.

After thirty seconds, it subsides with Walker’s resignation:

"Never enough

No.

Never enough.

Then: satisfaction. The low drone begins to menace and the promise is fulfilled: that soaking in sound, what their friend MILO described to Sunn O))) after a gig to as a sound “so incredibly present from where he was placed that he was inhaling pure frequencies in a way similar to the technique of cranial-sacral massage”. Prompted by this I can’t help picturing Brando’s Kurtz, smoothing his hand over his bald pate, half-eclipsed in shadow, quoting TS Eliot’s ‘The Hollow Men’. Throughout Soused, Walker’s remarkable, elliptical lyrics have the broken meter and layers of imagery of the modernist poet.

How is that guitar tone? It is actually slightly less present than the torrent of previous recordings; smoothed over, burnished to a black shine by Walker and co-producer Peter Walsh, under the musical direction of Mark Warman.

But the foreboding spirit of the sound-bed on ‘Brando’, punctuated by Walsh’s lashing whip-cracks and a strange slide whistle effect, speaks to the core of the Sunn O))) enterprise. The Sunn O))) that started experimenting with slow-mo lava-flow guitars on the Grimmrobe Demos and ØØ Void: “BREATHE IN THE HEAVY!” as the old Sunn amplifier advertisement instructed.

"A beating

would do me

a world

of good."

Walker confesses, with the blows hammering down.

What follows is the sheer drama of the chord change.

The former pop star fled the fame of the Walker brothers to a monastery to study Gregorian chant. He understands the power of these profound, Earth-shaking shifts. They exude Dread and Fear. Take the solemn, unnerving low strings from Angelo Badalamenti’s ‘Fred And Renee Make Love’ from the Lost Highway soundtrack, and compare it with the low summoning and spare acoustic guitar that introduces ‘Farmer In The City’ on Tilt.

It’s what makes the mid-way point of ‘Cue’ from The Drift one of the heaviest moments in music ever, as the Ligeti-like frenzy seeps back to reveal a deeper darkness and the orchestra swells: “From the fat black crocodile on the sand bar/ Can’t swallow it then bury it/ From the voice flooded semen clotting to paste/ Can’t swallow it then bury it.”

These ancient creatures are drowning in the bubbling tar pits of Soused‘s cover imagery. Like the dinosaurs on the edge of the precipice in Seldon Hunt’s (very OTT) liner notes to The Grimmrobe Demos, they are “something darker than possibility”.

There’s something new going on here too. The synth pulsing underneath (not unlike that underpinning ‘Face On Breast’ from Tilt) imbues it with the throbbing energy of Cliff Martinez’s soundtracks to Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive and Only God Forgives, work in turn that follows the soundtrack work of John Carpenter in his prime. Assault On Precinct 13 – the barbarians are at the gates. The same barbarians that gate-crashed (“BAR! BAR! BAR!”) the memorably titled ‘SDSS1416+13B (Zercon, A Flagpole Sitter)’ on Bish Bosch.

Here Walker trades more excessively in recurring motifs, the archetypes, which make this more immediate and accessible than that album, more so, in fact, than most of the work of Sunn O))). The guitars supply sonic cement as the songs cohere satisfactorily, returning to lyrical themes and musical motifs.

It works because Sunn O))) and Scott Walker share the primitive ‘big dream’, delineating what psychoanalyst Carl Jung described as “an ancestral heritage of possibilities of representation” where “civilised man is not yet entirely free of the darkness of primeval times”.

I interviewed Julian Cope some years ago about this regarding his own collaboration with Sunn O))) on ‘My Wall’ from White1. On that track he invokes the pagan landscape of Wan’s Dyke, otherwise known as Woden’s Dyke, a Roman earthwork slicing west through Wiltshire for sixty miles towards the Bristol Channel.

Cope’s lyrics (again, not without silliness) situate us firmly back, before and Beyond Rome: “Play your gloom axe Stephen O’Malley/ Sub bass clinging to the sides of the valley/ Sub bass ringing in each last ditch and Combe/ Greg Anderson purvey a sonic doom.”

He explained: “One of the reasons why heavy metal occasionally sounds like religious music is because religious music is inherited from heathen times, and so when you reduce music to its lowest common denominator it goes down to those modes that were most useful to the ancient people.”

Sunn O))) bring primal experiences to religious sites: Dømkirke was recorded live at Bergen Cathedral in 2007. They turned Miles Davis’ ‘Little Church’ from Live-Evil into the ‘Big Church [Megszentségteleníthetetlenségeskedéseitekért]’ of Monoliths & Dimensions.

Just so, on ‘Brando’, Walker is found in devotional attitude: “I am down/ on my knees.” Soused is clearly intended to be a useful album.

This might sound overdone but we live in a time when an enigmatic tribe is forced to retreat to a mountain, fleeing an ideological savagery that shocks our sense of reality anew. How are we meant to interpret these times? What tools do we have?

Though it makes reference to the Stasi, second track ‘Herod 2014’ reaches back further in history and holds a mirror up to the present. When people are being beheaded in the ancient landscape of the Middle East by terrorists, 21st Century barbarians, ‘Herod 2014”s interpretation of the biblical massacre of the innocents is no historical fiction, but a present tragedy. It has become a nightmare made real.

“She’s hidden her babies away”, Walker laments as the guitars shift uneasily around a figure, as malevolent as the black metal explorations of ‘Candlegoat’ from Black One. There is a life support machine keeping time, a saxophone squealing, the manipulated lowing of some undefinable creature, moments of piped silence and mystery, and some beautiful poetry: “Their soft, gummy smiles/ won’t be gilding the menu.”

“And why bring them out/ with no shelter on offer”, he asks. The detail of the disease and despair, the forsakenness of the scenario is etched into the imagery: “Bubonic, blue-blankets/ run ragged with church mice.” A song for the forsaken, a sanctity desecrated.

“Posed, high,/ Pelvic bridges” and “Pearly bone/ mountain ridges” coalesce to draw a landscape of the internal. The moon shines “bright pain” on their faces, as the tension tightens and tightens. It’s almost unbearable and the interludes that promise respite only emphasise this dread.

This is the closest Walker comes to incantation, repeated refrains in the fissures of the tectonic plates: “I’m closing in./ I’m closing in.” As the wind swirls: “I’ve come searching,/ from far and away”, for the messiah that can’t be found. Walker’s use of motifs analogous and directly taken from mythology creates what Jung called “the deposits of the constantly repeated experiences of humanity”. Humanity: doomed to repeat its mistakes.

‘Herod 2014’ is the centrepiece of the record: doom-laden, fundamental, ineluctable: if only the Yazidis could have escaped into the Sinjar Mountains, to the stone city that Mayhem vocalist Attila Csihar described on Sunn O)))’s ‘Aghartha’: “In memories of the consciousness of the ancient rocks, / nature’s answer to the eternal question.”

‘Bull’ introduces a hammer-on-anvil beat and a change in mood, some of the chaotic play and bodily obsession of Bish Bosch is resumed, the simile “Leapin’/ like/ a River Dancer’s/ nuts” recalls the protestation of ‘Corps De Blah’ where “Grinding upheaval/ always affects the genitals”. And this track with its clattering drums has sonic equivalence with David Bowie’s last album, and the industrial tint of his mid-nineties work, his collaboration with Trent Reznor and ‘I’m Deranged’ from Lost Highway.

Soused is the nearest twenty-first century equivalent to that partnership. Bowie’s admiration for Walker is well known. In retrospect, ‘Plan’ − a bonus track from The Next Day featuring a bone-dry beat and shoegaze guitar − seems to suggest a direction for Soused. “Custodiunt migremus” – “Keep movin’ on.”

The song relents to the drone once again but it takes on a different function, its use becoming less extreme, less bold, as a Sabbathian bell tolls in the distance – it fades to a conclusion.

This subtler style is picked up again in the sheet metal grind and horn of ‘Fetish’; the stabs of Guy Barker’s trumpet enacting “Red, blade points” that “knife the air”. An up-close Walker describes his protagonist afflicting a body with some kind of sadistic instrument – “it’s [sic] blackness/ glistening/ Curling/ and winding/ through/ grip-mangled/ fingers”. This works extraordinarily well: cold instruments of sex described by a form of rock music resolutely devoid of sexiness.

“Gleam away/ little brute./ Gleam away” and the track passes almost to silence, and with it the more structured excursions of the first half of the album disperse, replaced by a wooziness, and circus mirror distortions.

Cruel inscription follows:

"…he carves

the ghost

mascot

the length

of his skin.

“Stilettoed

without interruption,

“The body

including

the face."

The drums burst in. “There is/ No nothing/ else” he resolves and the jagged chaos bleeds away for the ringing drone to begin again. It’s as if when Walker escapes for air, for mischief, Sunn O))) drag him back into the depths. ‘Tell us/ apart,/ we can never/ die” he accedes as drums return and the guitar shift along with them.

This track also throws up the album’s grossest imagery (note, “bescumber” means “to spray with shit”): “Can’t afford,/ but bescumber,/ our/ spunk-stiffened/ tresses.” Fifty Shades of Brown Note, here’s that follow-through I mentioned at the top. The impression left is one of a seance of intimacy: a requiem for a dream with eyes wide shut. “Fluffed/And the/ fluffer/ fluffing/ goodbye.”

Soused ends with ‘Lullaby’ – a song originally written for Ute Lemper in 1999 – on which this collaboration seems to find its unique voice. Walker throughout the album has been the conductor in that he is orchestrating proceedings, but here he truly seems to channel Sunn O))): “In vain I/ douse/ another lamp.” A Newton’s Cradle seems to keep rhythm and the amps burn quietly in the background: “Tonight/ my assistant/ will pass among/ you.” Bearing an empty cap: “The most intimate/ personal choices/ and requests/ central to your/ personal dignity/ will be sung.”

Then it breaks into a piercing white-out hi-synth overlaid with off-key sing-song based on William Byrd’s ‘My Sweet Little Darling’: “My sweet/ little darling/ My comfort/ and joy./ LULLABY/ LA LA.” Just as much as they have plumbed the depths, rooted out primitive truths − “Why don’t painters/ paint their cloudy/ spires/ chiaroscuro/ the way they/ used to?” – the subjects of this portrait of pain are trapped in some kind of inner space; Janus-faced, beholding the past and anticipating the future.

On White1‘s second track, Sunn O))) opened ‘The Gates of Ballard’: JG Ballard, who said he could “see a time […] when time will virtually cease to exist. The present will annex the future and the past into itself”. Technology can be used to remove the best part of our brain and the internal, those “intimate personal choices and requests” spill out: “…we are moving into a realm where inner space is no longer just inside our skulls but is the terrain we see around us in everyday life.” Aghast at the world, time freezes and we collapse inwards, our fears and desires are externalised.

At the start of another Nicolas Winding Refn film, Bronson, Tom Hardy’s imprisoned and insane Übermensch is introduced with ‘The Electrician’, one of the final Walker brother’s songs: “…when lights go low/There’s No Help/ No.” He is the solitary man, who paints pictures of himself; a tormented animal, which torments itself. Bronson displaces his personality but the visceral intensity of his physical presence remains emphatic.

This is the defining truth of the nature of this collaboration. On the surface, Scott Walker gives himself over to the raw power of Sunn O))), displacing himself; when it gets interesting is when this transferral starts to run in both directions. They are the mystery men at the end of the line. Walker is speaking to them.

Soused moves from the monumental to the intimate: a retrograde zoom from the apocalyptic desert, the broad river, to the room, the body, the mind. In doing so it’s a compelling and highly listenable work. It’s not comfortable, it’s not easy. The mythic dream is frightening reality. You can’t sing yourself to sleep anymore.