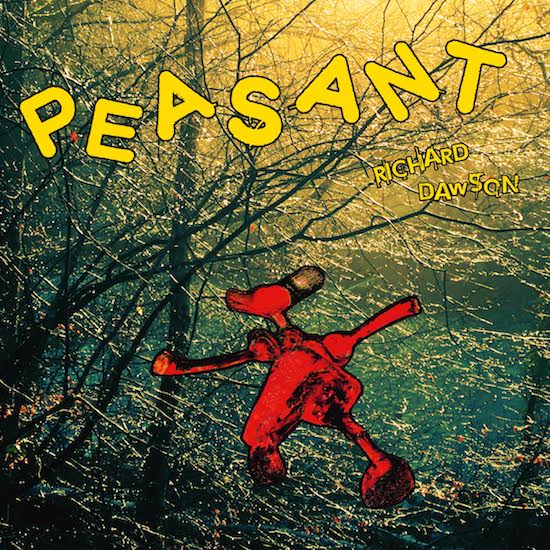

Richard Dawson has said that he really believes in Peasant, his first new album since 2014’s breakout Nothing Important. And you should think so – given that, from its structure and instrumentation down to its most basic themes, it is a bold and almost complete break with the style that allowed him to cross over from the weirdo underground to his current position as the country’s best-loved exponent of avant-folk.

Confessional tales of underage drinking sessions gone awry are replaced by a kaleidoscope of character pieces displaced to the pre-medieval Northern English kingdom of Bryneich, while the barebones sound palette of ribcage-busting vocal and spidery electric guitar seen on his previous opus have been replaced by a multi-layered, kitchen-sink ensemble aesthetic. Yet perhaps the most notable move Dawson has made in Peasant is the ambition of its central theme: how community can be reclaimed as a meaningful force in society.

Community is a word that he mentions a lot in interviews, and one that’s closely connected to another term that he’s expressly uncomfortable with – folk music. Since the folk revival of the mid 20th century the term has increasingly slipped from referring to the canon of anonymous song passed down through generations to sensitive singer-songwriters a la Nick Drake – a shift towards folk as a generic term and away from a functional music made anonymously, by and for the community. Now, it’s become essentially an aesthetic – see Mumford and Sons and those top hat-wearing bourgeois gypsies you get at festivals. Perhaps that’s why Dawson is more keen on the term “ritual community music”, suggesting something more primal and yet more pertinent to our times. Peasant, a cobbled-together beast of pop, free improv and acoustic and ethnic music, might be said to embody that new kind of functionalism.

Album opener ‘Herald’ gets things off to a tentative start, all muted brass arranged in placid tone clusters and chirruping stabs. It’s a far cry from the pompous fanfare one might expect from the title – an allusion to the neuroses-tinged jingoism of post-Brexit Britain, perhaps? – giving the sense that the presentation of a society made in this album will be probing and exploratory rather than celebratory. Next, lead single ‘Ogre’ starts with a pretty, Alasdair Roberts-gone-Calypso theme, before massed vocalists set the scene on Bryneich, their handclaps and Eastern modality bringing to mind the traditional qawwali music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. With its strident earworm melodies, it suggests something far removed from the wayward and brittle tones of Dawson’s previous album, approaching something quite near to pop in its sky-punching coda, Rhodri Davies’ starburst harp twinkling majestically at the edge of the fray.

Texturally, Peasant is Dawson’s most lush work to date, if lush is indeed the right word – more a prickly thicket of brambles than a bed of moistened leaves, with creakily bowed strings, spiky rushes of acoustic guitar and occasional splurges of noise. ‘Shapeshifter’ opens with the kind of liminal acoustic zones that Dawson has explored as part of Hen Ogledd; ‘No-One’ explores weirdo bedroom noise in the vein of Richard Youngs; ‘Masseuse’ extemporises over stoner-doom riffage while throughout Dawson’s flurrying guitar work is like some offspring of Derek Bailey and Bola Sete. This is a stiffened sonic patchwork, allowing Dawson to tightly weave a tapestry of a community gone wrong.

After the hod-carrying social outcast presented in ‘Ogre’, Dawson proceeds to give life to the other denizens of Bryneich, cutting lattice-like through the social fibre. While ostensibly set in the Dark Ages, the stories presented here are pitched at universal themes, their characters serving as archetypes mirrored throughout history up to the present day. ‘Weaver’, for example, seems like a rather faithful rendering of a medieval workman with its detailed descriptions of the artisan’s methods and daily duties. This specificity soon broadens, however, to the point where we know that Dawson is actually creating a more universal portrayal of a small-town gossiper: “Combing through the fibres, searching for a yarn to spin.” ‘Soldier’, meanwhile, paints a picture of an angst-ridden warrior on the eve of battle. Personal and political anxieties soon intermix, however, the soldier’s fears over the coming fight overlapping with his longing for his lost love, declaiming: “How I yearn to hold you once again.”

The bleakest and yet most tender portrait, however, is ‘Prostitute’. In a rather audacious attempt to place himself in the mindset of an embattled sex worker, Dawson presents a terrifying vision of a dehumanised psyche: “There has to be more than this / Is there no reason for me to exist / But for as a plaything / Love miscreants, malingerers, dastards and knaves?” There’s something uncomfortable in this attempt to render the consciousness of one of society’s oppressed, an audacity that some may balk at. In this portrait, Dawson flies in the face of the discourse, inherent in today’s identity politics, that holds that lived experience is an impassable barrier, and that artistic expression is always confined to the purely “experiential” – the social context of the artist being inescapable. With such intimate portrayals as ‘Prostitute’, however, one gets the sense that Dawson is attempting to breach such barriers by dipping into the psychologies of different sections of society, attempting to uncover commonalities and the causes behind its fractiousness. An allusion to this could be found in ‘Shapeshifter’, where Dawson references the folkloric tale of a fox disguised in a man’s clothing, perhaps mirroring the songwriter’s attempt to mimic his subjects. It’s also worth noting that, while the ten identities presented on the album are thoroughly distinct, they all come under the banner of the Peasant of the album’s title. Scientist, beggar or masseuse – we’re all in the gutter.

Dawson has cited Bruegel the Elder as an inspiration for his new album’s making, and the comparison is certainly pertinent: like the Flemish master, we get a survey of a society, with minute details brought to the fore. The vignettes of Joyce’s Dubliners also spring to mind, as do the characters created by Chaucer, who used archetypes to lampoon and interrogate the hypocrisies of public life in his time. One gets the sense, however, that in searching beneath the skin of British culture, Dawson himself is actually searching for a positive message, suggesting that, while the scabrous underbelly that has afflicted us since the Dark Ages remains, there is the potential to live together with empathy. He has described Peasant as “A panorama of a society which is at odds with itself and has great sickness in it, and perhaps doesn’t take responsibility – blame going in all the wrong directions.” Though the community portrayed on the album is certainly imbued with a sense of fractiousness, it’s clear that the potential for change is always there. Notice, for example, how the album’s bleakest lines are always mirrored by unremittingly positive counterparts. On ‘Soldier’ the line “I am tired, I am afraid, my heart is full of dread” alternates with “My heart is full of hope," while on ‘Ogre’ the pop refrain of “When the sun is dying” is neatly offset by the lyric “when the sun is climbing.” While we may be beggars, prostitutes or ogres, there is always the potential for change.

Politicians use the term “community” when they really mean “demographic”, and togetherness is nothing more than a marketing buzzword. On Peasant, Richard Dawson searches for a way that we might reclaim these ideas. Through the empathetic exercises of lyrical role-playing or the creation of a personal folk tradition through ritual community music, Dawson suggests that we can regain an authentic sense of community by seeking out commonality.