There is a strong power of suggestion that whatever Pharmakon album you pick up is meant to upset you in some way. The psychic dread Margaret Chardiet brings to her work is a logical result of her examinations into how different aspects of human life can deteriorate. Her fourth album with the project, Devour, looks at systemic failure through cannibalisation on a micro and macro level.

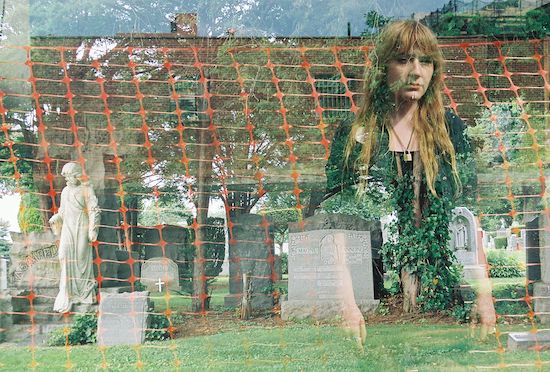

The aggression of Pharmakon’s albums always begins with the artwork. Each sleeve is perfectly composed to be grotesque, whether it features offal or Chardiet’s face being groped by sweaty fingers or, in the case Devour, a close-up of her chowing down on a death mask. You could skip her artist statements and still know before the opening crash that there is something hideous she wants you to feel.

Chardiet growls and distorts her vocals to the point where her lyrics are hard to decipher; they may be better left unknown. Harsh sounds and distorted vocals are all part and parcel of noise compositions. As on previous work, Devour begins with immediate, startling sounds that shape our understanding of the work as intentionally challenging, if not pointedly unpleasant.

The idea of collapse is not a new theme in Pharmakon’s work. Fatalism as relates to the body was the central theme of 2014’s Bestial Burden. Following a sudden illness and hospitalisation, Chardiet used the album to work out her feelings about how the body can breakdown without warning. On Devour, it’s clear that Chardiet sees social and environmental breakdowns as the next logical steps beyond self-destruction.

Because so many of the sounds she works with have a metallic timbre, songs evoke associations with factories and furnaces. It is, again, the power of suggestion in the mechanical beats of ‘Spit It Out’ that bring to mind the repetition of machinery or an old fashioned train chugging along its tracks. It’s in the bright, staticky sounds of ‘Deprivation,’ like sparks shooting out when metal clashes against metal. Knowing her intentions, we can connect factories to black clouds and overworked employees and a rarified few who can foist responsibility for destruction and suffering on someone else. But it starts with that one relentless, mechanical chugging.

It’s these subtleties that make Pharmakon frightening. Some artists use samples of screams or other tortured human sounds for atmosphere, but Pharmakon has maintained an uncomfortable intimacy by recording her own voice for these sounds, treating them like any other vocal rather than a sound effect. The fade between ‘Homeostasis’ and ‘Spit It Out,’ features Chardiet’s own belaboured breathing. It’s striking as an organic moment amongst so much synthesised dissonance, and is maybe the closest we ever get to her voice without an effect on it, but it will sound distressingly familiar to anyone who has ever had a panic attack.

Rhythm plays a strong role in all Pharmakon albums, but Devour has a stronger pull and a denser composition. One rhythmic track layers on top of another, sometimes swallowing each other up and sometimes taking songs into different directions. The breathing of ‘Spit It Out’ fades under a heartbeat throb, one panic mollified by the repetition before Chardiet’s distorted vocals bring the tension back in a shocking relief.

It’s disturbing how easy it is to be lulled by repetition. Even the most aggressive sounds can become soothing once your brain adjusts to them. The seasick movement of ‘Pristine Panic/Cheek By Jowl’ gives way to a teeth-gnashing thud, a whirlpool receding into a riptide then sucked back again, all the while dragging you with it. What other noises have we become inured to? What news reports are we now dulled to? With a high enough signal-to-noise ratio, the worst of things still get through to us, in the same way a few of Chardiet’s uglier words come through: Annihilation. Oblivion.

Pharmakon is well equipped as a project to examine a collective collapse. She understands that destruction isn’t just what happens to us or around us, it’s what we contribute or fail to contribute to the order of things. Devour isn’t a rallying cry for change, it’s a reflection of the ugliness of it all, from the inside out. This critique is not some passing fancy of hers; even if she moves on from the idea that society is eating itself, there will be a new aspect of impermanence to explore.