As the pandemic loomed over London in 2020, Patrick Wolf was living in a Lewisham tower block where he cut the desolate figure of the Arthurian Fisher King. A wounded protector surveying his barren kingdom, gripping onto the Holy Grail of his voice as he drank himself into oblivion. Neither alive nor dead, a man very firmly on the edge.

Twenty years before, when Wolf first emerged, he was seen as the next break-out star alongside Amy Winehouse. His first two albums Lycanthropy and Wind in the Wire were an almighty deluge of high-octane fucked-up acid folk, cut with a classically trained balladry that absorbed a cosmos of instruments and was supremely suffused by Wolf’s baritone. Others elsewhere such as Animal Collective may have been playing with the same millennial paradox of sacred and electronic, ritual and replay, but Wolf’s sound had a personal and spiritual velocity to it that made it feel dangerous.

The fact Wolf was also a recalcitrant figure ratcheted up his appeal further. Young and laser-focused, he stood at odds with the major labels and rejected demands to change his unconventional sound to produce something more consistently radio-friendly – in particular during the recording of 2007’s major-label debut The Magic Position.

Wolf always felt on the cusp of something until all of a sudden he never felt further away from it. After a run of six albums in eight years that ranged from well-received to acclaimed, he dropped off the map in 2012. Since then rumours of a return have faded in and out of the very real reports of the tragic events that have befallen him in the interim. For more than a decade: death, bankruptcy, and addiction were all we heard, until Wolf re-emerged in 2023.

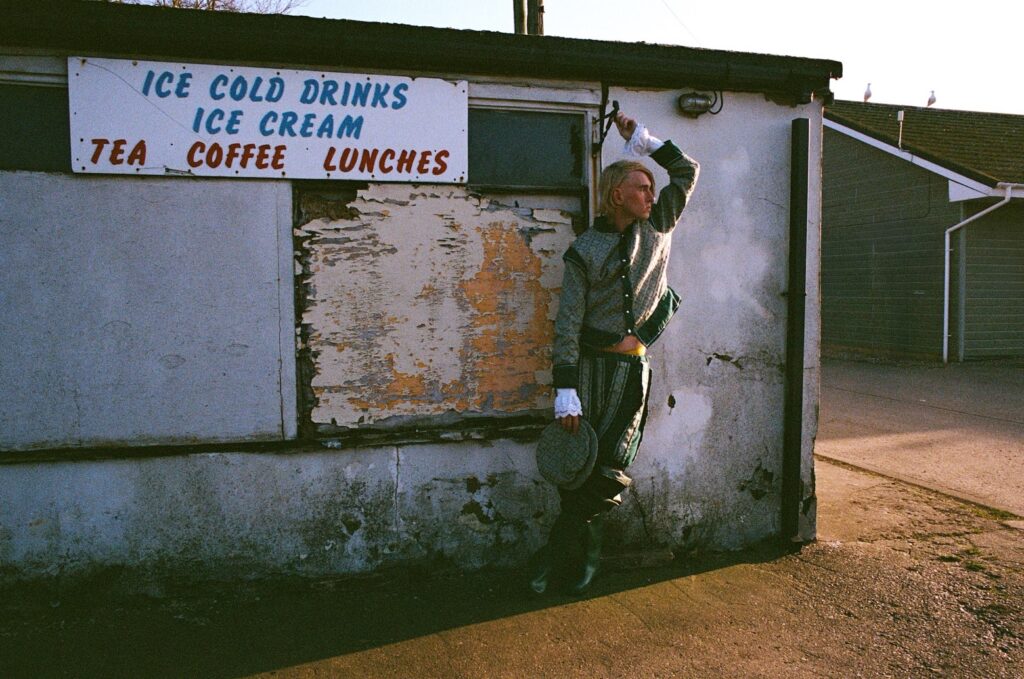

He had found sobriety during the pandemic and left his Lewisham flat to seek peace in east Kent. A salt-scented place of glorious landscape and deep spiritual resonance – but also the genius loci of this Kingdom’s madness.

Wolf deeply immersed himself in Kent’s landscape, histories, and rituals. He took day-long peregrinations along the coastline. He devoured all the pamphlets from the local historical association. He consulted folklore experts to better understand rituals. It was almost like a ceremonial forgetting of London. And it’s from this absorption that his first album in thirteen years Crying The Neck is born.

Monumental opener ‘Reculver’ sets the tone, played out across a complicated but melodious set of three time-signatures. The track, whose rough form was conceived when Wolf was 16 and completed over two decades later, unifies his years of pain, when he was “bankrupt and borderline / orphaned and obsolete” with his later salvation where he was able “to find all the words”. In a duality that mirrors Reculver’s twin towers near Herne Bay, it feels like a cleansing of Wolf’s decade of silence – the bridging of a supposed ‘lost’ period.

However, it’s also haunted by a spectre, one that pervades the entire record: the fractured psyche of Kent. Kent is ritual and landscape, but also the frontline of Brexit-Britain. Its place name, one of the oldest in the English language, also serves as its function – for Kent translates roughly as ‘land on the edge’.

Wolf becomes the latest in a long list of radical artists to have their imagination overtaken by the unknowable depths of Kent’s subconscious, joining author Russell Hoban who wrote Riddley Walker about it, Charles Dickens who set his final work The Mystery of Edwin Drood there, and David Seabrook who wrote All The Devils Are Here, a deep psychogeographic work concerning east Kent.

The album’s staggered triptych of songs (‘Limbo’ / ‘The Last of England’ / ‘Hymn of the Haar’) that concern the tortured side of Kent is its mythic spine. ‘The Last of England’, in particular, a clear tribute to Wolf’s long-term inspiration Derek Jarman, pulls no punches. It’s a grand rhapsodic track that Wolf calls “a National Anthem that I wrote for myself”. Here he mixes Arthurian legend with Boris bullshit, singing how “The Green King deep in Doggerland woke” to find a country “rotten to the core” by that “madness in June”. Under a sky of soft starlight keys, it’s a reminder of how deep rituals of the land can be transformed into empty political motions.

Kent’s current crisis-state is most tragically captured in harrowing ‘Hymn of the Haar’. In it Wolf recounts seeing a dead migrant boy “the shape of a balloon” washed up under the Dover cliffs, where it “came clear there was no rousing him”. Like the boy, who Wolf initially assumed was asleep, the song is locked in an eternal dreaming.

However, the genius of Crying the Neck is the nesting of Wolf within the county. For this record is far from soapboxing. It is a simple absorption and accountability of what has transpired. Much as Wolf himself has moved on from his string of tragedies to create something beautiful, what fuels this record is the belief that this is possible on a grander scale.

Tracks such as ‘Oozlum’, referring to a mythological bird that flies backwards, and ‘Better or Worse’, which describes the Kentian ritual where a wooden hobby horse dies and returns with magical powers, point towards the importance of moving forward to avoid being consumed by the past.

The clearest demonstration of life after tragedy is found in ‘Dies Irae’, which lies at the exact heart of the album. Dedicated to Wolf’s mother, who died after a battle with cancer in 2018, it’s a song of renewal in death – of the beauty of the next day. In it Wolf is able to fold in all the hallmarks of his sound: the electronic frenzy of Lycanthropy, the ascendant and mythic howls of The Bachelor, and the pop sensibility of Lupercalia. And in an album which seldom uses the word ‘love’, when Wolf utters “I love you too” at the end of the song, it’s a solemn and life-giving moment. It’s also perhaps his greatest song.

In Crying the Neck, a man on the edge and a land on the edge both fall into one another. And instead of making a greater abyss, they end-up supporting one another, creating something like the dolmens that populate the county. A cathartic, erudite, and complex work that serves as the beginning of a new chapter for Wolf – both in east Kent and in his music, the two now seemingly forever intertwined.