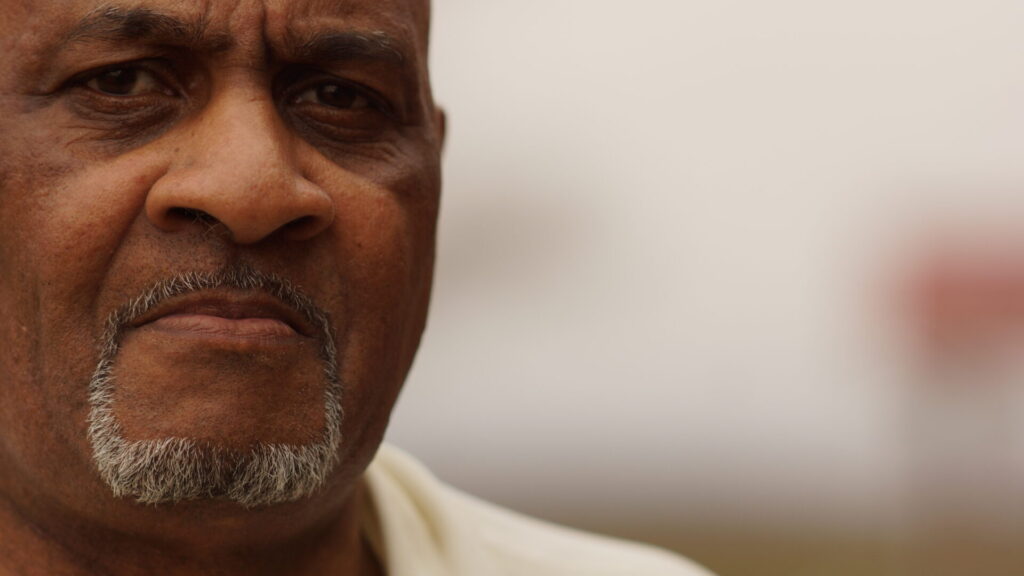

Parchman Prison Prayer: Another Mississippi Sunday Morning was recorded in the course of a single day at Parchman Farm, the vast Mississippi State Penitentiary. It is performed entirely by twelve inmates of the jail, men aged between 24 and 74. The prison has been notorious for more than a century as a place of repression. It was run, effectively, as a punishment camp for Black Americans, described by Ta-Nehisi Coates as ‘the gulag of Mississippi’, and is still cited as an example of everything wrong with the US justice system. The prison-plantations of the Deep South, of which Parchman was perhaps the most reviled, lay at the heart of segregation in the USA, and in some ways they have not changed. In 2022, the Justice Department found that conditions in the prison violated the constitutional rights of prisoners.

Yet, despite its continuing, brutal history, Parchman is also a place of resistance, and part of blues legend. Song collectors John and Alan Lomax visited five times between 1933 and 1959, recording many songs in both the men’s and women’s camps. Some became famous, including the Civil Rights anthem ‘Oh Freedom’, and ‘Poor Lazarus’ which featured on the Oh Brother Where Art Thou? soundtrack. Eighty years on, inmates are still expressing themselves through song – a tradition born of adversity, but one which shows the importance of music for those who have little else.

Parchman Prison Prayer opens with perhaps its most captivating track, ‘Parchman Prison Blues’. It could be heard as a response to the classic blues song ‘Parchman Farm Blues’, recorded in 1940 by Bukka White on his release from the prison, and covered many times since by artists from John Mayall to Jeff Buckley. The men come together for all of two minutes, twenty-eight seconds as the Parchman Prison Choir. They hum together in improvised free harmony. There is a deep, deep bass rumble, a high tenor, a drift of distinctive male voices leaning into a two-note figure together, expressing their internal melodies as a group. The sound is almost certainly unlike anything else you have heard, unless you are familiar with the Gaelic free psalm singing of the Outer Hebrides. It is unfettered expression rooted in religion, in blues, and the isolation felt by residents of a Mississippi maximum security prison.

The album is called Another Mississippi Sunday Morning because it is the sequel to 2023’s Parchman Prison Prayer: Some Mississippi Sunday Morning, which received very enthusiastic reviews. Both were recorded by US producer Ian Brennan, who has a formidable record of tracking down previously unheard performers in places the music industry rarely looks. He won a Grammy in 2015 for Zomba Prison Project, an album recorded inside Zomba Central Prison in Malawi. He brings his signature techniques to Another Mississippi Sunday Prayer which, as well as being recorded in a single day, uses only live first takes, and contains no overdubs. Brennan just listens, and what he hears is extraordinary.

Another Mississippi Sunday is a stranger, less polished album than its predecessor, although polish is a relative term on a record where the sudden appearance of a piano comes as a jolt. Some of the tracks are almost fragments, clocking in at under a minute. They are not made or played for any conventional audience. It is impossible to imagine what spending time in prison is like if you have never experienced it, and we have no idea how these men got there. The songs sung on the album are both private consolation and social currency – a way to communicate in a place designed to nullify self-expression.

Some tracks have a mantic quality: intonations which bind private spells. The whispered ‘Take Me To the King’ feels almost like an intrusion. The performer, D. Justice, is in dialogue with the deities, laying himself open: “I don’t have much to bring / my heart is torn to pieces / here’s my offering”. It is music as a ceremony that opens up channels of communication beyond the physical realm. Each performer has his own style and, while D. Justice speaks, others really sing. J. Hemphill showcases his impressive gospel voice on two short tracks, ‘Living Testimony’ and ‘Open the Floodgates of Heaven’. On the former, his unaccompanied singing is rich and powerful. On the latter, his raw vocals balanced with a stately piano could be Nick Cave with a higher range. The track could be from The Boatman’s Call. They are over in the blink of an eye, and linger all the more as a result. Hemphill has been in prison most of his adult life.

The most surprising track on the album pays tribute to MC Hammer. The song, named after him, is performed by J. Robinson with L. Stevenson, who presumably provides the beatbox accompaniment. Over a remarkably delicate whispered soundscape of pops and wire brush swishes, Robinson raps, “All bass line no treble”, about “Holy Spirit dancing like MC Hammer… too legit”. MC Hammer is not usually taken seriously, but this track challenges us by responding to his work in an open and vulnerable way. It is self-expression in a form that makes us re-evaluate our assumptions. The song stays with you long after it has ended.

The most moving piece on the album is sung by the oldest performer, seventy-five-year old C.J. Deloch. ‘I Won’t Complain’ is a triumphant, unaccompanied blues sung with a fire that hits the back of the room. An old man behind bars in a notorious jail sounds freer than the rest of us put together. The two longest tracks are both performed by M. Palmer, whose deep Southern voice intones rather than sing, with a natural authority many singers would kill for. ‘Grace Will Lead Me On’ tells a story about his family, breaking down in turn in different parts of the house as they tell him about ‘grace’. It is dramatic and affecting. ‘Jesus Will Never Say No’ closes the album, and Palmer takes the lead while others add backing vocals and play as a small band, revealing just how skilled they really area. As the album ends it becomes clear just how good these men are. They nail their single take with skill and understanding. In that moment, they are musicians, not prisoners.

There is not a single duff track on the record, which is intense, heartfelt and committed from start to finish. Brennan has given us the opportunity, and the privilege, of hearing the voices of men who would otherwise be beyond our awareness. The album shows us quite clearly how music can live in anyone’s soul, and how people disregarded by society can use its power to make something compelling, strange and positive, telling the stories that matter to them. Another Mississippi Sunday Morning is folk music, in its truest form.