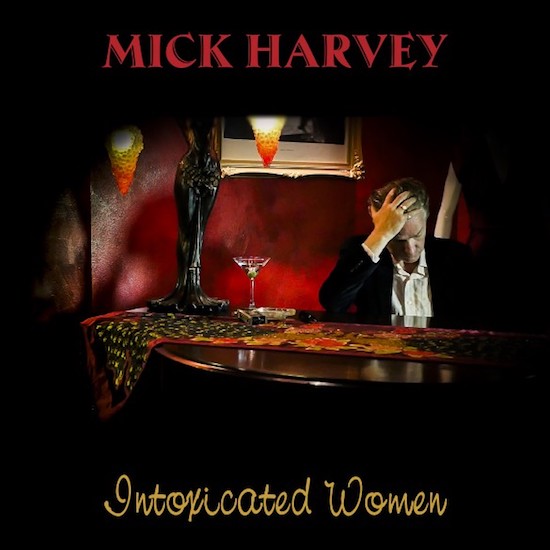

It was Heraclitus who said you never step into the same river twice, and yet Mick Harvey is now four albums deep into his Serge Gainsbourg project. While after Intoxicated Women he’s promised to stop, it’s clearly a habit he’s finding difficult to kick. His first, Intoxicated Man, named after a popular Gainsbourg song of the same name, arrived in the mid-90s when the figure he was seeking to emulate was more a recondite rebel than a cult concern to most outside of his native France. Serge was known, of course, for a raunchy holiday hit recorded with Jane Birkin that your mother might have copulated to – it was de rigueur in ‘69 after all – but he wasn’t known for a great deal else.

A few years after Gainsbourg’s death in ‘91, The Birthday Party / Bad Seeds guitarist had been given a mixtape by a French friend, causing something of an epiphany. He had time on his hands with Crime & the City Solution’s dissolution, and soon he found himself embarking on the strangest of hobbies. Intoxicated Man was released in 1995 through Mute, and Pink Elephants followed in 1997, retaining the bibulous titular theme, with the title track the only song Harvey himself penned in this series, co-written with orchestral arranger and Parisian man-about-town, Bertrand Burgalat.

You might have thought that was it (certainly Harvey probably did), but – two decades on – he’s resurrected the project, with last year’s Delirium Tremens making an appearance, and now finally, Intoxicated Women in 2017. It’s been a herculean feat of persistence and fastidiousness, which has seen him reinterpret and translate around 56 Gainsbourg chansons from the well-known to the obscure. Harvey appears to have grown in confidence with each outing, a progression that’s been fascinating to watch.

The surefootedness of Intoxicated Women wasn’t quite as detectable in the 90s, with, say, his version of ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ seeking to stick to the script musically as much as possible. (Though it did demonstrate his cunning regarding innovative ways of interpreting a song.) Gainsbourg’s duet – also with Brigitte Bardot – was itself a direct translation of letters written by Bonnie Parker; rather than retranslate the lyrics in some counterintuitive Beckettian way, Harvey went straight to the original source and put the epistles to music. Similarly, on ‘Lemon Incest’, he went back to basics.

“Gainsbourg took his favourite melodic composer, Chopin, and put pretty much his most famous single melody to a disco beat,” he told me when I interviewed him for FACT magazine in 2014 when the first two albums were re-released. “So I thought the logical thing to do was take it back to the original simple piano.”

Harvey’s recording back catalogue otherwise features 14 studio albums with the Bad Seeds, around 12 with other bands and 11 soundtracks; he’s performed with other artists too (a recent trip around Europe and North America with PJ Harvey immediately springs to mind), but as a solo artist, the Gainsbourg repertoire is half his own recorded output. Having racked my own brain and thrown out an unfruitful s/o on Twitter, that amount of attention covering the same source seems unprecedented (although you may know different). Certainly Scott Walker recorded a number of Jacques Brel songs over three albums, and Brel became the key influence of his early solo work, though the chansons were intended more to blur into his own musings, and he had Mort Shuman doing much of the heavy lifting with the translations. What’s more, Walker’s versions were almost etiolated held up to Brel’s guttural, bellicose chants, superficially easy listening with only a trace of the uneasy listening we’d come to expect from him later hiding deep within somewhere. Harvey on the other hand sets out invariably with faithful intentions – certainly throughout the first part of the project – and it’s only when he comes back to it during the 21st century that he starts to be more playful and irreverent once he’s really got the hang of things.

The two recent volumes also arrive at a time when Serge has never been more revered here. Sylvie Simmons’ excellent 2001 biography A Fistful of Gitanes, and patronage from Jarvis Cocker, Portishead, Beck and Harvey himself, has helped elevate the dead Frenchman to demigod status this side of la Manche. In that regard, this final volume is less about exposing the world to Gainsbourg’s genius, and more about having fun with the material. The first few volumes, it’s fair to say, were a miscellaneous selection from his three decade career with no overarching themes. On Delirium Tremens from last year, Harvey excavated some recherché treats, collaborations and songs lifted from soundtracks (Gainsbourg had a successful concomitant career as a soundtrack writer as well as as an actor and director) and from other unexpected places, with a few old faves thrown in. The final selection here includes chansons written when Gainsbourg was on the cusp of greatness himself, but making a buck as a one-man Tin Pan Alley for the Yé-yé generation. And more importantly, in keeping with the title, we get a bunch of songs that were either written as duets, or written particularly for women. As a result, there are a host of collaborators here, including Andrea Schroeder, Channthy Kak, Xanthe Waite, Jess Ribeiro, Sophie Brous and Lyndelle-Jayne Spruyt, as well as the very male sounding Solomon Harvey (presumably some relation) on ‘Baby Teeth, Wolfy Teeth’.

‘Dents de Lait, Dents de Loup’ was originally recorded as a duet with Frances Gall, and there are other more famous Gall numbers here too, including a more subdued and beatific version of her triumphant Luxembourgian Eurovision entry ‘Poupée de Cire, Poupée de Son’, and the controversial ‘Les Sucettes’. Interestingly, ‘All Day Suckers’ as it is called here, is one of the only songs where Harvey’s chosen not to duet with anyone, even though Gainsbourg wrote it specifically for Gall. That could be down to the suggestive lyrics, which imposed on a female singer like Gainsbourg imposed them on Gall could easily be deemed as a bit creepy. “Annie loves all those suckers,” Harvey croons over the singsongy nursery rhyme-like tune, “as the slippery sugar perfumed with anise flows into her throat / Annie finds it heavenly.” Gall, who was 19 at the time, apparently didn’t detect the double entendre, and neither did her manager father. The chanteuse was reportedly distraught at having been duped, inadvertently causing a scandal. Gainsbourg, who was twice her age at the time, probably should have known better.

One duet that makes a reappearance is the afore-alluded-to ‘Je t’aime (moi non plus)’ translated not only into French, but on the new offering, into German as well; as a resident of Berlin for so long, he’s fluent in the language. By making his German version far more raunchy than his earlier English rendition, Harvey challenges received wisdoms about which languages are supposedly sexy and which aren’t. Perhaps that wasn’t a specific intention, but where the first rendering felt slightly tentative, here he hits it out of the park with the pashing and the heavy breathing. Is it as steamy and seductive as the French original with Brigitte Bardot, or even the priapic international smash with Birkin? It’s certainly difficult to maintain associations of eroticism with a song that’s advertised everything from yogurt and perfume to a pint of John Smiths. Whatever the answer – and it’s more a rhetorical question than anything else – sparring with the monstre sacre a second time demonstrates delightful impudence from a man now clearly having the time of his life bashing these songs out. ‘Ich Liebe Dich… Ich Dich Auch’, featuring Schroeder, finely exemplifies the confidence Harvey has acquired reworking Gainsbourg’s oeuvre over the years.

There are no songs here that don’t work, although several predictably struggle to achieve the greatness of the originals, given how familiar and how loved they might be. ‘Prévert’s Song’ for instance, is a fine folk tribute presuming you don’t know the former, but ‘La Chanson de Prévert’ has a hymnal, funereal quality, and is a popular song at French wakes, almost making it too much of a sacred cow to attempt. Well almost. And there’s something delightfully romantic about the fact Harvey has translated lyrics into English that originally came through Gainsbourg via the pen of Verlaine – the chanson is based on parts of the poem Les feuilles mortes. And Harvey concludes with a faithful and suitably epic production of ‘Cargo Culte’ – how could he finish with anything else? – but given the fact the conclusion of Histoire de Melody Nelson is truly one of the most monumental crescendos in all of recorded pop music, it would have to go some way not to fall short, which it inevitably does.

Picasso once said, or maybe it was Stravinsky, “good artists copy, great artists steal”. The best tracks throughout this series were the ones where Harvey innovated, rather than just copied, and it is these songs that will likely be played more often than the straight counterfeits. At the end of the day, if you want to listen to Gainsbourg, the likelihood is, you’ll listen to l’homme lui-même. Whatever the intentions originally, Harvey has tacked himself onto the Serge Gainsbourg story, even if Gainsbourg himself wasn’t complicit, in the same way Gainsbourg augmented the works of Chopin. Artists throughout history have recreated masterpieces from bygone eras in their own image, but when it happens in pop music, it’s a little more unusual, and often causes more consternation.

Intoxicated Women might well be the last album of its kind, but there are more places Harvey could go, and given that it’s a process he enjoys so much, why not? How about more German offerings? Songs written for pop nymphs from the 80s (Isabelle Adjani, Vanessa Paradis, Charlotte Gainsbourg etc)? Film soundtrack instrumentals perhaps? It’s strange to note that were the former Bad Seed to attempt recording another collection in five years time, he’d then be within the realms of producing music beyond Gainsbourg’s own lifespan.