Friedrich Nietzsche’s infamously dense philosophical novel Also Sprach Zarathustra was modestly described by its author as (in Walter Kaufmann’s 1966 translation): “the greatest present that has ever been made to [mankind] so far. This book, with a voice bridging centuries, is not only the highest book there is… it is also the deepest, born out of the innermost wealth of truth, an inexhaustible well to which no pail descends without coming up again filled with gold and goodness.”

Nietzsche might have had sardonic intent here, of course; but perhaps not. The novel, whose title translates as Thus Spoke Zarathustra (named after the Persian prophet who founded Zoroastrianism, a religion concerned with the binary conflict between truth and falsehood), rails against conventional 19th-century morality and was seemingly constructed to avoid easy interpretation. The same could be said of Laibach’s artistic output in its many and varied forms over their three and a half decades of confounding and befuddling critics and delighting their fans.

Laibach share Nietzsche’s aptitude for provocation (declaring again that god is dead in Also Sprach Zarathustra and being the first western rock band to play in North Korea elicited similar levels of media outrage and mockery in different eras) as well as putting weighty thought into their efforts, with much confusion resulting as to the whys and wherefores. Nietzsche’s use of the term superman (übermensch) has hardly done his popular image any favours in the wake of the Nazis’ enthusiastic adoption of the term and its corollary üntermensch, both of which came from Also Sprach Zarathustra.

Likewise, for Laibach, whose emergence in post-Tito Yugoslavia in the 1980s came complete with sardonic uniforms and symbolism, their presumed association with the extremes of political ideology does not survive close examination. A band from the former Eastern Bloc performing selected hits from The Sound Of Music in front of the assembled ranks of North Korea’s ruling elite on the occasion of the country’s 75th anniversary of the liberation from Japanese occupation takes trolling to the next level, with panache.

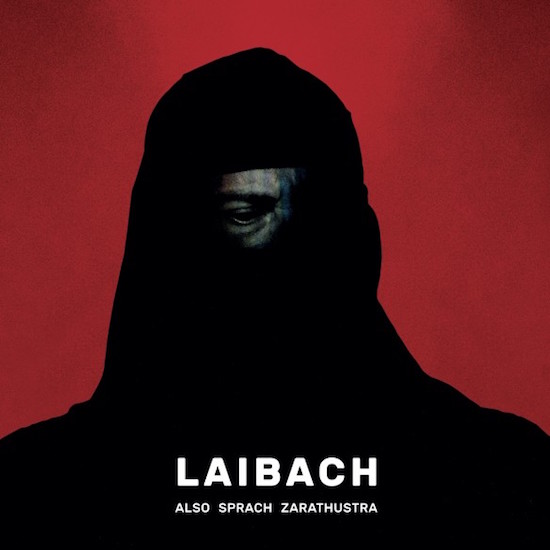

Their latest album is adapted from their soundtrack to a theatrical adaptation of Nietzsche’s novel, directed by Matjaž Berger for the Anton Podbevšek theatre in Novo Mesto, Slovenia, in the spring of last year, and was recorded with an orchestra. Given Laibach’s penchant for charged cover versions, it’s almost surprising that there’s no remaking in their own image of Richard Strauss’s ‘Sunrise’ from his tone-poem Also Sprach Zarathustra, as made over-familiar by 2001: A Space Odyssey and a thousand portentous opening credits and introductory themes since. But there was no real need to do so; this is Laibach at their most stentorian and intense, and it might even be their magnum opus.

Laibach have made a career out of theatricality, often with the explicit intention of making a double-edged point, sometimes so subtly as to fly swiftly over the heads of fans and denigrators alike. Anyone expecting thumping industrial techno visits to pop-cultural tropes will not find them here, exhilarating as Laibach’s reconstructive take on the poptastic (‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ or ‘Life Is Life’, for example) and the revered (Bob Dylan’s ‘Ballad Of A Thin Man’ or ‘See That My Grave Is Kept Clean’ by Blind Lemon Jefferson) have been and will doubtless continue to be. However, the music here is not that distant thematically from Spectre, an album that coincided with the launch of their political (anti-)party of the same name in 2014.

Milan Fras declaims Nietzsche’s words (in the original German, of course) with the gravitas and wholly convincing delivery of an iron-willed demagogue, his timing and ominous charisma making for a gripping performance. While this may not be the Laibach album to slip on the playlist at a party (WAT still holds that place, thanks in particular to the stomping ‘Tanz Mit Laibach’), it pulses frequently to a compulsive electronic rhythm as the orchestral moments swell up to emotive peaks, from the somewhat Straussian opening to the recapitulation of the closing motif. This is an expressionist, almost ambient companion piece to the plentiful hooks and luscious production of Spectre, channelling the likes of Popol Vuh by way of Einstürzende Neubauten, the sound of knives being sharpened leading into instrumental passages that perfect the interplay of ponderous beats with sonorous strings and woodwind.

This is no mean feat in an age when classical collisions with electronic music abound, let alone the overdone trope of rock bands getting symphonic and pompous with the aid of an orchestra – and this is hardly Laibach’s first foray into any of those areas. Also Sprach Zarathustra is as often unsettling as it is impressive, the close-miked sound of chewing and panting among the rising swells of ‘Das Glück’ or the hearty snores and metal percussion of ‘Das Nachtlied II’ making for particularly shuddersome moments as the sweeping synthesizers and fed-back klang enfold retriggered beats and gelatinous samples. Likewise, the flawless arrangements, composition and production recalls the best parts of the cinematic soundtrack to the space opera Iron Sky and harks back at times to their avant-industrial score for a theatrical production of Macbeth in 1987.

Laibach seize every opportunity on Also Sprach Zarathustra to bring out the grandiose psychodrama and tension inherent in a founding tract of modern philosophy, rendering what could have been merely bombastic and brutal as spectacular and even sublime. It might not be greatest present that has ever been made to humanity, but it is a resoundingly impressive feat.