Justice are always at their best when their concepts are clearly defined. Their second outing, 2011’s Audio, Video, Disco, wasn’t a bad album per se, it just suffered from a lack of direction. There was some kind of plan in place, presumably to channel Goblin, King Crimson and other ornamental 70s rock behemoths through the medium of electronic music and turn everything up to eleven; what we got was a form of musical libertarianism run riot. Indulging in prog fantasies is a dangerous business, and can precipitate punk exploding in your face if you’re not careful.

Following an era defining debut like † was always going to be a precarious trip along a dangerous path, and Gaspard Augé and Xavier de Rosnay approached it in their characteristic fashion, dancing insouciantly through a minefield. They were victims of their own successes – not that they would ever regard themselves as victims. To be clear, Audio, Video, Disco would be considered a masterpiece in the canon of most other bands, but Justice aren’t other bands. They set the bar too high for themselves from the off by releasing a debut that was a game changer, 21st-century dance music’s own Fosbury Flop (its influence on Skrillex and other purveyors of EDM over the pond is well documented). † is a finely-tuned, turbocharged thrillride; poised, streamlined and controlled and featuring innovative banger after innovative banger, making Justice one of the most vital sounding pop groups on earth in 2007. There’s really only one way you can go from there.

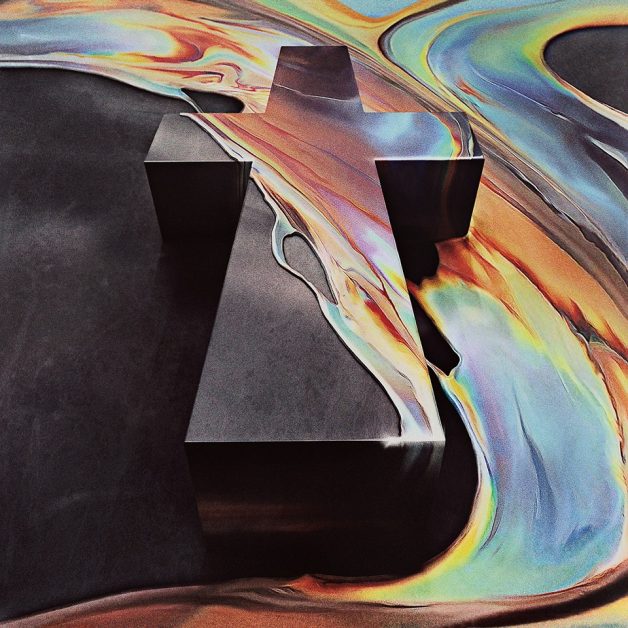

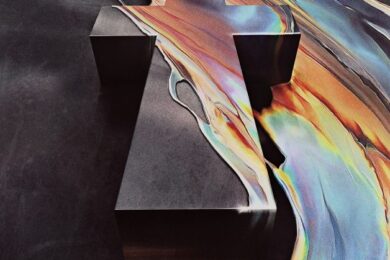

Through it all – from the highs of touring to the recent five years of laying low – there has remained one constant: the cross. The rood of Justice is rarely spoken about, but its abiding presence brings an added dimension to the duo, the aphonic third member in an unholy trinity. Again the concept is simple and almost Warholian: to extricate a symbol with so much meaning attached to it and pass it off as your own, is an audacious postmodern annexation worthy of Drella himself. As trained graphic designers, it would be easy to imagine the strong visual concept came before the music. Well it did come before the music in a way, 2,000 years before. While plenty of evangelicals would probably disagree, Justice claim to use the symbol in a “straight and almost respectful” way, neither blasphemous nor provocative. They’ve taken an icon with a rich and sometimes violent history – that means something hugely significant to millions of people – and they’ve used it to their own ends, altering what it actually means to their own followers. It’s a stroke of appropriation bordering on genius, conceptually simple yet remarkably effective.

Which brings us to Woman, the French electronic duo’s third long player in eight years following a lengthy sabbatical. For the first time in their careers, the inception of the record began with that one word, and everything else came thereafter. It’s a tribute to the women in their lives they say – not just the lovers, but the mothers, the sisters, the friends… Women are life givers, so why shouldn’t they be the inspiration for a record, even if such homage feels slightly old fashioned. As per usual, Justice are as forward thinking sonically as they ever were, and as strangely anachronistic at the same time. They are rock stars in the electronic sphere, icons in the age of the faceless DJ, 70s men in a world of focus groups and spin. Their music is always progressive but overtly beholden to its influences.

You get the impression the pair make music to please themselves first and foremost. It’s the kind of nonchalant disregard for what others think that sees them set up a twitter account (@JusticePourTous) and then never follow anyone and never tweet; the kind of devil-may-care attitude that allows them to begin ‘Safe and Sound’ with an unrepentant vajazzling of ear-popping slap bass and somehow get away with it. It’s their unwillingness to conform, or dance to anyone else’s tune, that makes their music so life-affirming and unique.

If Woman is an homage to women, it’s also a love letter to the music Gaspard and Xavier listened to when they were growing up, the analogue synthpop classics and the krautrock, the power ballads and the chansons. It’s fair to say, Woman approaches the medium of songwriting – and specifically the aspiration to create the perfect love song – with a studious and sometimes serious intent, and it’s also fair to say that being sonic chansonniers suits them.

‘Love SOS’ and ‘Stop’ (featuring vocals from Romuald and Johnny Blake respectively) are atmospheric paeans to fidelity, albeit with as few lyrics as possible on the former. At times they dispense with the troublesome and time consuming process of writing lyrics altogether, and their instrumental offerings certainly don’t suffer as a result: ‘Alakazam’ channels the exuberant neon anthems of Gary Numan, the mighty ‘Chorus’ takes the blueprint of German techno and makes it even more mechanical and forbidding if that’s possible.

As Frenchmen, they have expressed anxieties about rhyming “season” with “reason” (on ‘Fire’) and other such elementary poetic practices, but for them, English is the pop lingua franca, the preferred language of the pop stars they listened to growing up. That certainly rings true, as the Toubon Law, which requires 40% indigenous language quotas on all French radio broadcasts and on television, wasn’t passed until 1994, while it was around the same time that yéyé and the chansons from the late 60s and 70s started becoming fashionable again. Their formative musical years during the 80s and 90s were anglophonic but for a few notable exceptions.

In 1971, Serge Gainsbourg recorded the concept album Histoire de Melody Nelson, and while it started its commercial life as a slowburner, it has since become a classic of such magnitude that it’s hitherto the yardstick by which all French pop is judged. At some juncture in every pop career in France, this record will be referenced or cited as a key influence, and its with Justice’s third album that Gainsbourg is invoked. Or more specifically Jean-Claude Vannier, the orchestral arranger whose gifts gave Melody Nelson its otherworldly sonic edge.

The vertiginous, swooping strings on ‘Safe and Sound’ certainly imbue “the spirit of ecstasy” running through the half-hour magnus opus, and when I pointed it out to Justice while interviewing them for FACT Magazine a few months ago, they admitted they’d thought about trying to secure the services of Vannier, before electing instead to collaborate with the London Contemporary Orchestra.

“We’ve worked with other orchestras before,” said Xavier, “and what’s often tricky with classical musicians is they can sometimes have a hard time with syncopation and understanding what you want, especially with disco music, which is so remote from what they normally do.”

Versatility is the LCOs modus operandi, and as well as being a working orchestra, they also double up as a choir. Their vocals appear on ‘Safe and Sound’, and on the seven-minute epic ‘Chorus’, which – with its celestial “ahhs” – undoubtedly references that other seven-minute epic ‘Cargo Culte’ at the conclusion of the Gainsbourg record. To suggest Justice have in any way tried to replicate the 70s album would be a stretch, but it would be fair to say Woman borrows some of the motifs from its predecessor, and could be regarded as their own Melody Nelson for the digital age.

What’s more, the marriage between classical and rock had been barely explored before Gainsbourg and Vannier tried it in 1971, and the results were flabbergasting at the time. It’s been done countless times since of course (the 90s were awash with alternative bands utilising strings) but nothing’s ever quite measured up to the seminal chef d’oeuvre. Disco and strings have always been a thing – the Philly sound would be nothing without orchestration – but laid over the cold, hard techno Justice produce makes for a more unusual and remarkable melange contemporarily, in the same way that Melody Nelson was a phenomenal stimulation of the senses in 1971 (and still is in 2016 to be fair).

Woman is a heartfelt homage, sometimes preposterous, occasionally cheesy, always compelling and invigorating. Justice’s mission was to unify the clinical electronic music they make with the humanity of the chanson and the warmth of manual strings, and as a result they’ve created a sentimental cyborg of distinction. While the original concept was a simple one, the result is no less extraordinary. After a slight misstep with Audio, Visual Disco, they’ve only gone and created a masterpiece with Woman.