In December last year, a video went viral of trainee producer Nobuo Kawakami presenting an AI project to film director/animator Hayao Miyazaki. He showed to Miyazaki how the CGI animation “…learned to move by using its head. It doesn’t feel any pain, and has no concept of protecting its head.” Miyazaki, though, was repulsed by Kawakami’s work: “Whoever creates this stuff has no idea what pain is… I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself.”

In their defense, the producer was using his imagination in order to create something distanced from humanity as we recognise it – a technique horror artists frequently employ. But what Miyazaki, perhaps, was repulsed by was the removal of the figure’s personality and the elimination of its potential pain – the reduction of a familiar human-like body parts to a limping mannequin. But whatever constitutes ‘personhood’ for Kawakami seems eerily out of mind during the presentation, only expressing interest in the mechanical processes involved in the figure’s movement.

Personhood and its relation to the body, though, is far from the sole domain of visual artists or animators – it’s also a topic that frequently permeates contemporary music. Gazelle Twin’s art work for the 2014 albumUnflesh, for example, is a Photoshop collage job – a slice of meat protruding from where a face ought to be, underneath her familiar blue hoodie. The vocal manipulation on her album, too, alters the personality of her inflection. A year later, Arca’s visuals for ‘Mutant’ depicted a bulbous 3D model with vaguely human features and a plastic glean. The album art that accompanies Spectres’ 2017 Condition is an uncanny 3D object; a queasy imagining of the human body entwined violently in twigs and organic tissue. There looks to be an excessive hypochondria here concerning the human body as a deteriorating object, with personality and life absent from the model’s contorted, ashen face. It would be tempting to throw Björk’s Homogenic artwork into the equation here, but the key difference is a power and personality to her alien self-presentation, as she told the Chicago Tribune in 1998, Alexander McQueen’s given brief was to model a “warrior” who “had to fight not with weapons, but with love.” With Arca, Spectres and Gazelle Twin the figure and artist both looks and sounds dead, sick, bringing out (sometimes not so subtly) the intuition that there is something uncanny – something “wrong” with it.

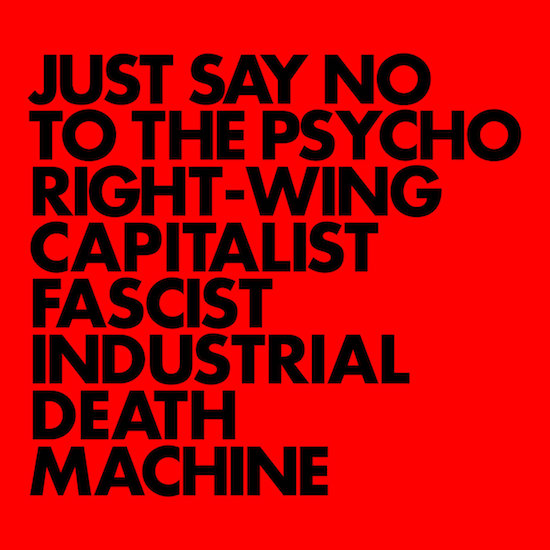

On their newest album, Just Say No To The Psycho Right-Wing Fascist Capitalist Death Machine Gnod join the ever growing list of musicians concerned with personhood, dehumanisation and physical deterioration. But their approach is different – they are distinctly non-fantastical in their presentation of people – their lyrics capture everyday details, such as the state of someone’s nails, their hair, their work failures and private behaviours. Where those other artists previously mentioned provide an implicit, ominous reference to dehumanisation through visual means, Gnod are explicit in their references, picking out situations and conditions of human exploitation and obscenity.

Gnod bring to the cultural foreground a ‘truthful’ depiction of modern society. ‘Paper Error’, one song is titled. ‘Bodies For Money’, another. There’s a sizeable history behind them, too: Otto Dix with his naturalist paintings of Industrial Age/Weimar socialites, whores and businesspeople; Mark E Smith’s dealer on ‘Carry Bag Man’ and “corners filled with hitmen” at ‘The Steak Place’; Magazine’s The Correct Use of Soap; Sleaford Mods’ Nathan Barley-esque character assassinations. Gnod, though, are far more interested in abstract personhood than The Fall or Sleaford Mods, making their distinction between “bodies” and “people” at the point of entry via song titles.

‘Bodies For Money’, for example, is a jarringly direct opening track, both musically and lyrically, allowing for imaginative projections of the Amazon workers who camped outside the warehouses in order to save money. There are no characters, no personalities to charm here – and amidst the long hours of productivity, there is no Saturday Night & Sunday Morning domesticity to provide fleeting comfort. The voices on ‘People’ are distant, indiscernible, paranoid, terse and high pitched – invoking sensory overload. “We always get what we deserve,” Gnod’s vocalist Paddy Shine intones over a growling bass that falls in on and over itself. It’s another invocation of the throwaway Capitalist phrase “the cream will rise to the top”; the simplistic idea that hard work consistently translates to the personal successes (and finances) of the individual.

No personality or individuality are allowed to encroach upon Just Sat No… until the album’s penultimate track: ‘Real Man’ is a caustic, unforgiving account of a man’s hyper-masculinity, social insecurity and physical imperfection. Shine ruthlessly deconstructs the antagonist – his “cauliflower ears,” among other criticisms of his physique – sarcastically adding, “he is not appreciated.” And, putting aside the more overt homage to The Fall’s ‘Hip Priest’, it’s also the only clear character study of the Mark E Smith persuasion. Gnod’s lyrics are comprised mostly of hyper-familiar idioms; industrial metaphors like “cog in the machine” are deeply imbedded in the Anglicised memory, so often repeated in every day use of the English language that its status as metaphor is all but forgotten – no interpretation is required. Gnod turn over and refresh the dirt on their graves, a reminder of the industrial images in Chaplin’s 1936 slapstick political comedy Modern Times.

Gnod’s commitment to exposing the harsh and the grim in society is equally persistent through their music – these aren’t ‘sweet’, harmonically pleasing pop songs; they are a ‘horrible sound,’ something not exactly unexpected if you are already familiar with their previous albums (or any other music which hints at extremes). ‘Extreme’ or noise music, though, isn’t particular to the 21st century – Throbbing Gristle alone would provide strong enough argument for that. Gnod use their noise and their distortion in a way that suits the contemporary political atmosphere: they purposefully avoid the ambiguity that went with Throbbing Gristle’s détournement of Nazi concentration camp imagery.

But Gnod’s use of noise is similar in their confrontation of the hateful and disturbing head-on, with the fact of its 2017 release making this album more of a direct anti-Capitalist political revolt against the kind of wallpaper ambience that wouldn’t be too disruptive to a Starbucks coffee morning. (And, with an album title like Just Say No To The Psycho Right-Wing Capitalist Fascist Death Machine, you can’t imagine the café branch sticking them on their playlist any time soon.) Whether you like it or not, Gnod’s music is present – undeniable, even – especially in the quality of its vocals. A slurred, wailing cadence – slightly, presciently, off-key.

The final track on Just Say No…, ‘Stick In The Wheel’ is also the album’s most musically diverse moment. Consisting of two parts, the first not dissimilar from the preceding tracks, the second offers a change in tack: the drums no longer splash – they’re so soft that Gnod even sound like they’re about to get out the brushes. The fills are jazzier too, the tempo is wound right down and there is an introduction of film noir soundtrack piano. This slow yet still tense conclusion is an effective contrast to the jumpier, guitar-centric tracks and perhaps it’s a shame that there aren’t more of these, acting as interludes. But the relentlessness of the album’s pace has its own particular dimension; it’s not a record where moments of introspective pause are given space – or where you’re given chance to breathe.

On Just Say No To The Psycho Right-Wing Capitalist Fascist Death Machine Gnod aren’t exactly saying much that’s new – but that isn’t important here. It’s a re-iteration of a stance – like making your own banner for a protest; everyone else has one, but there are particulars within the wider issues that you make the choice to foreground. Gnod join the others expressing concerns about Western society – concerns of dehumanisation, robotisation of work and the sense that “time is running out for people.” Being a musician in the UK (or being involved currently in any kind of creative profession) is precarious. Even more so with

This album is distressing to hear, as are all other albums that take on a similar cause – but this is mainly because there is something deeply familiar and non-mystical about their political concerns. Resistance to the Death Machine and all of its adjectives is wholly important at our precise time in history, but it would be another step forward to see constructive imaginings or even demands from artists for the future of a humane society.