Punk’s relationship with Turkish culture appears to manifest in two distinct, fairly separate ways: the Turkish left’s perception and criticism of it, and the adoption of the music style by Turkish youth culture. The latter influence evolved in a more intuitive, heavily stylistic way, in that Turkish teenagers in the late 70s and 80s appreciated the space it gave them for self-expression and as escapism from what was expected by them in mainstream culture. This musical history hasn’t been articulated with much depth until recently, given a thorough and somewhat detached analysis in An Interrupted History of Punk and Underground Resources in Turkey 1978-1999, co-written by Sezgin Boynik, Tolga Güldallı and published by the Istanbul artist space BAS in 2007. The book documents punk’s role in Turkish society in the window of these decades, providing a critical leftwing commentary.

According to Boynik and Güldallı, the Turkish left in the 70s and 80s were interested in the ideas behind punk but mostly took it as being symptomatic of “imperialism, Western decadence, decay and apoliticism. Those who criticised punk were aware that it was an agent and a warrantor of Western democratic capitalism and that it could go hand in hand with the IMF (even though it appeared to be opposing it).” The adoption of punk did not, then, happen via the more cynical organised Turkish left, but via teenagers and their initial interest in Western heavy metal. This wasn’t on a calculated basis of political theorising, but more in the form of intuitive reaction – the music provided “…space [for] youths who refused to accept the degenerate arabesque culture imposed on them and who sought some breathing space within this assimilated, dehumanised society”. The first band in Turkey that labeled themselves ‘punk’ was Tünay Akdeniz ve Grup Çığrışım, which was in 1978 – in order to allow for comparison, this would have coincided time-wise with Germfree Adolescents by X Ray Spex, Wire’s Chairs Missing and Throbbing Gristle’s D.O.A The Third And Final Report in the UK. This Turkish music stylistically has more in common with the 13th Floor Elevators and American garage psych than punk.

Having been born in the mid-80s, Gaye Su Akyol was too young to be a part of the original alternative scenes in Istanbul, being more wrapped up in the music that she would have had access to via Turkish Radio Television or her parents’ music. This is in part due to the fact that the punk scene in Istanbul would have found it nearly impossible to pass on its ideas via mass media. After all: with no access to social media most Turkish teenagers would have relied on major broadcasting companies to get an idea of what was happening in their own country – and this would have been, to put it lightly, a very restricted take. Gaye Su Akyol, then, was only exposed to alternative music some time after the military coup in the 80s, during which newspapers were destroyed and journalists were jailed – with certain forms of expression becoming restricted by a new constitution formed by coup leader Kenan Evren. It was as a teenager that she discovered artists outside of Turkey – picking up Nick Cave, Joy Division, Sonic Youth and Einstürzende Neubauten – less influenced by the punk and garage rock music of other Turkish punk bands before her and more impressed upon by Western experimental music that emerged at a slightly later date. But Gaye Su Akyol still carries on that original idea: that Turkish punks can’t just pastiche the clichés of Western punk.

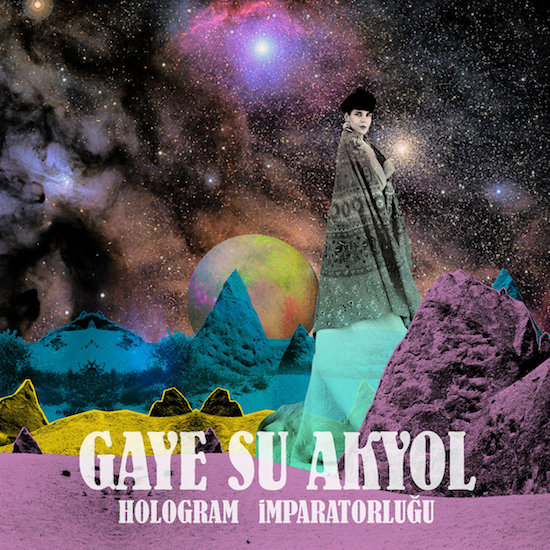

Hologram Ĭmparatorluğu – her second full release, better produced and more aggressive than her debut, Develerle Yaşıyorum – is heavily influenced by the music that Gaye Su Akyol would have heard on mainstream Turkish media, rather than an a churlish attempt at a disconnect from her time growing up on Arabesque and classical Turkish music from her parents: regardless of whether or not she fully appreciated the fact that her music listening was restricted, this was the situation into which Gaye Su Aykol was born.

Unlike the teenagers who discovered heavy metal in Istanbul during the 70s, the young Akyol was not hankering after the outward looking escapism from her culture. In the late 80s and 90s, she claims mostly to have listened to the singers Selda Bağcan and Müzeyyen Senar who, though associated with older, Arabesque and classical Turkish music, are neither more kitsch or less political in tone. The music of Selda Bağcan in particular would have been more relevant to the ordinary Turkish person than punk music at the time – especially for the older generations, to whom Selda was associated with the political left in Turkey, imprisoned for her views during the coup.

Gaye Su Akyol’s epicentral, classical singing style establishes a divide between herself and the Turkish equivalent of the punk singer before her; simultaneously dramatic and sad, it can be loud and piercing, though sometimes drops into contemplation. The buried Western influences are made visible through Ali Güçlü Şimşek’s guitar playing on ‘Hologram’, as well as in the production involved on the various layered guitars – a kind of 80s post-punk production style, using quiet, subtle rhythm guitar to ‘bulk out’ the track and give it greater propulsion; the illusion that the track is ‘moving forward’. This driving sound that Gaye Su Akyol’s band draw – from new wave as well as those post-punk influences – is interesting in combination with the time signatures that they choose to use. Unlike in Western popular music, which mainly features 4/4, 2/4 and waltz time in popular music, Turkish folk has always adopted a wider range of signatures: 5/8, 7/8, 9/8, 7/4, and 5/4 being common alongside those found often in popular Western styles. Similarly, ‘Kendimin Efendisiyim Ben’ features a sauntering, distant sounding guitar riff that accentuates the theatricality of Akyol’s vocals. Running alongside the political lyrics of Selda, Gaye Su Akyol makes reference to the climate of contemporary Turkey in ‘Dünya Kaleska’’s lyrics of “You sold us out well! /You have a palace but/It’s just empty four walls /Possessions mangle mortals.”

It would be a disservice to view this album in terms of how Western artists have impacted on its making – rather, in listening to Western bands like Sonic Youth or Einstürzende Neubauten, it allowed Akyol to realise that conventions were not the same as restrictions; that, for example, she could place electric guitar riffs alongside vocals influenced by classical Turkish styles. This new Turkish alternative scene, with Gaye Su Akyol being its illustrative frontwoman, has been afforded the ability to compare their own music and cultural situations to that of Western artists – much more so than the Turkish alternative musicians before them. It’s a scene which also includes gothic rock band She Past Away and Bubituzak, whose members play on Akyol’s records. These artists are part of this continuous fight against cultural conservatism, although this has mainly impacted the importing of Western bands into Istanbul – Muse, Skunk Anansie and Joan Baez have cancelled gigs in the country in response to the failed military coup in July this year. Though with Akyol’s own album having an international release, playing festivals like Roskilde and Le Guess Who?, it will be harder for conservative forces in Turkey to silence this new wave that Istanbul now incubates.