One of the consistently problematic issues with regards to “folk” music in the 21st century is not one of authenticity or truth (although there are plenty of problems with that) but one of history – of how music taps into history to help us look at the way we live now. How the past conceptualises the present. The thing is, history these days is half dredged-up nostalgia, a yearning for an ideal past that not only doesn’t now exist, but which also never existed in the first place, while at the same time wilfully ignoring much of what is happening right now in the world around us. For a lot of folk music outside the enclaves in the UK where it still holds sway, what amounts to history for many an aspiring bourgeois folk musician is singing a Nick Drake cover or a half-arsed riff on Tam Lin, dressed in Farmers Market tweed, and sporting a wide brimmed hat that said musician never takes off, even indoors!

And so, when Alasdair Roberts arrives on cue with a new release, it comes as a blessed relief. Plying his music in a variety of guises for nearly 20 years now, one of the preoccupations of Roberts is how a music situated in the past and steeped in history can be wrestled from plastic nostalgia and made to live and breathe in our tech-accelerated present. No easy task, granted, but it’s not for a lack of looking and research: for several years now, along his many self-penned compositions, Roberts has recorded traditional compositions as well as studiously looking in to how our past informs the present in a cyclical rather than a linear manner.

In 2012, while as a resident at the Archive Trails project with the University of Edinburgh’s School of Scottish Studies, Roberts was granted access to the department’s archive of traditional folk songs recorded by Hamish Henderson and Alan Lomax. Those tales wrapped in song tell of a life on the edge of existence, of hardship that is almost impossible to comprehend today: the past of many in Scotland was nasty, brutish and short. In an interview for The Wire at the time he noted, “I always talk about myself being an experimentalist rather than a nostalgist in terms of drawing on the past. I like the process of renewal rather than comfort. It’s a myth, the whole idea of the rural idyll.”

These studies have informed the music he has released since. 2013’s A Wonder Working Stone mixed traditional skirling reels, blues-twanging guitar and communal singing with improv welsh rapping(!), with lyrical imagery and religious themes along with words that warned of the futility of violence and of demagogues who would use said myths for nefarious means. The blood, thunder and wine of A Wonder Working Stone was quickly followed by the plaintive Hirta Songs, a collaborative album with poet Robin Robertson, whose narrative that traced the stark and harsh landscape of the St Kilda islands, its nature and former inhabitants was matched by Roberts’ simple, yet beguiling arrangements. 2015’s Alasdair Roberts continued in this mode, an ostensibly solo record that captured Roberts in an introspective mood, looking to move forward in acknowledging Scotland’s bloody history of clans and defeat, but determined not to repeat it.

Roberts’ latest album, Pangs, is an attempt to bring a synthesis between the bolshiness of A Wonder Working Stone and the contemplation of Hirta songs and Alasdair Roberts. And it is an attempt that, ultimately, comes off with success. The mythic and lyrical themes, complete with multiple hermeneutics and Roberts’ high- register brogue are still there; in the opening track ‘Pangs’ and its accompanying video, a dishevelled and world-weary Roberts takes the role of a solder-king traveling across a threatening landscape to reclaim his seat and reunite his community. You could easily make the link to numerous fallen Scottish heroes and a nationalist yearning for independence, but if you understand Roberts and his approach to songwriting, he isn’t interested in cut and paste romanticism.

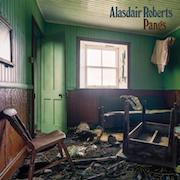

With Alex Nielson on drums and Stevie Jones on bass, Roberts reverts to the spine of a band format. But this collective is less rock bluster, instead they are more prone to daydream and wander through the songs. ‘No Dawn Song’, with its gentle waltzing meter, has Roberts reminiscing on the songs learned in his youth. “The Breach”, containing scraping drones of bass and cello mixed with traditional melody lines, breathes deeply, expanding and creaking like the old wooden walls depicted in the album’s artwork. The fluidity the trio have together in their playing allows the music to be relaxed and loose, but it is never ramschackle; the production work on this album feels organic and not deliberately lo-fi or scuzzed up. The blues guitar heard on A Wonder Working Stone is replaced on Pangs with clean finger-picking lines that cascade freely, while Nielson’s drums pitter and skitter with cat-like dexterity. This can be heard in the song ‘An Altar in the Glade’, where Roberts tale of a hunter chasing a deer through the wilderness, mixes highland song with warm tropical sea as guitars and tumbling toms are with lush glockenspiels.

The “rock” side of the group is not fully abandoned though; ‘The Angry Laughing God’ sees the band let loose with an earthy folk rock stomp that culminates in the gang joining in for some communal “Sha-la-la-la!” chanting. ‘The Downward Road’, meanwhile, is tale of portentous doom and menace, as banshee like whoops and howls accompany fleet footed fiddles, electronic squalls and guitars that are finally allowed to growl and bare their teeth.

Pangs is that album that while almost certainly comes across as “folk”, doesn’t feel stodgy or full of kitsch, fanciful, nationalistic symbolism that is as welcome as anthrax in the post. Roberts, an avowed internationalist, is more for using history as a springboard to try and create possibilities to bring people together in a sense of community and belonging instead of empty tribalism. Despite the low-key, crumpled, nature of the album, Pangs is full of warmth and charm, one that is welcoming instead of being difficult. If he isn’t already, Roberts is fast becoming one of the cornerstones that UK folk should be taking their cues from in the coming years.