The last time I interviewed Alan Vega he told me that while he didn’t fear death itself he had a visceral terror of the world that his young son was growing up in. When he spoke of how afraid he was to leave his boy behind it was with the same conviction you hear in Suicide’s ‘Frankie Teardrop’, an electro-rockabilly indictment of the callous horror at the heart of America’s imperialism in Vietnam, and one of the most harrowing yet honest pieces of music ever made. There’d been talk of a new Alan Vega album for years before his death at the age of 78 on 16th July 2016, but for a long time it seemed unlikely that anything would emerge. He’d suffered a stroke, had to recover from a violent mugging, and at Suicide’s final London concert in July 2015 appeared incredibly frail, despite a heroic performance that as ever saw them set fire to any idea of respect to their ‘heritage’.

The roots of IT can be heard in Vega’s last solo album Station (2007), an overlooked record of noise and yelling. Around its release he played a gig in the Camden Roundhouse’s tiny studio in which he was joined onstage by his wife Liz Lamere, who shook the bricks with gnarled electronics as Vega and their young son prowled around, shouting into mics. The familial energy was striking, strange and moving and, with Alan Vega using IT to sum up that world he was so afraid would threaten his son, a blueprint for what was eventually to come here. Lamere receives writing and production credit on IT, and it’s her judicious deployment of noise, rhythm, New York field recordings, and distortion under Vega’s formidable vocal performances that makes this his finest work since the first two Suicide LPs.

If Suicide was the sound of New York’s grim streets fighting back then IT is the last gasp of a Manhattan about to be lost forever under the totalitarian march of gentrification and redevelopment. Much of the album was made from recordings made during Vega’s wanders around his Wall Street home, clinging on in a rent control apartment as his favourite bars and haunts closed around him. It represents Vega’s long-standing icky relationship with the city. Present in the NY art scene of the 70s, Vega could arguably have become as known for his visual art as for his music, but was disgusted at where the money was coming from: "People getting wealthy on fucking Vietnam. The same people buying all the art. It’s blood money baby, it’s all about blood money," he told me a few years ago. In ‘Frankie Teardrop’ Vega had voiced the scream of the unknown warrior – he was hardly going to profit from its echoes.

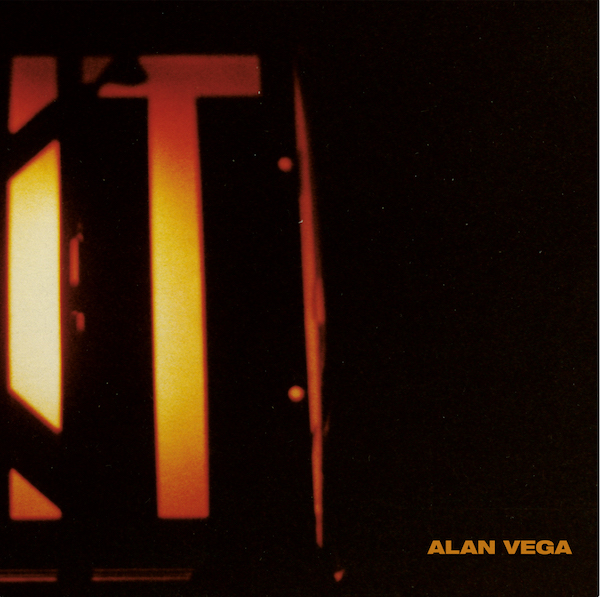

In IT though the two facets of his life’s work meet. The wraparound vinyl artwork splits a photograph of a building’s EXIT sign down the middle, giving the album its title. Inside are photographs of New York at night alongside wires and lights making sculptures on cruciform shapes, scraps of Vega’s writing (especially words like "cremations" "corpses" "blood"), arranged in a visual document and collage of city, life, death and power. If this is a record in which Vega consciously explored his own departure, it paradoxically, defiantly, electrically fizzes with life. It does this even when he shatters his own (and America’s) iconography. ‘Motorcycle Explodes’ has an terminal groove to it, methodical and violent underneath skids and screes of noise: "The skull is dead / the ghost is dead / the truth is dead". Rock & roll, the hot-rod American dream of the road that Vega loved and subverted for so long, is revealed to be gasket-blown and leaking oil too.

Last year, both Leonard Cohen and David Bowie released final albums in which reflection on their imminent deaths imbued every note. Alan Vega’s farewell is different because death – the violence of it on the streets of his beloved New York and America’s killing fields alike – was always the driving force of his work. As such this record has a curious trajectory. It begins martial and harsh and wonderful. He frequently sounds, in the most violent growls and snarls, like Mark E Smith tends to these days, but imagine The Fall listening to Bird Seed-era Whitehouse or Pansonic rather than old rockabilly and a Krautrock compilation pushed on them by the group leader. There is of course always that weird, accessible catchiness to his guttural croon, for Alan Vega’s love of Elvis Presley (who was only three years his elder) never waned.

IT sounds at times shockingly fresh and urgent, taking nearly everyone a quarter of Vega’s dying age who’s making serious, scabby electronic music at the moment and grinding them into irrelevance. Too often politics can imbue music yet feel like a pose. In Vega’s larynx there was never a chance of that. Yes, the harsh sloganeering about killing and America and racist bars might sound outdated to some but, well, he was right, wasn’t he? New York’s architecture might have changed since the early 70s but the surreal horrorshow of the American urban experience and the finance that underpins it certainly hasn’t. As much as a record about Alan Vega’s awareness of impending death, IT is a diatribe against the last decades of American politics, the Vietnam continuity through Iraq and Afghanistan, the violence that continues to sweep lives and limbs from the young men of rust-belt towns yet hands the votes of their parents to Donald Trump. "Red white and blue… it’s destroyed… there’s no more… just war, American war" is Vega’s blackened scream in the face of the establishment from that apartment down on Wall Street, right in the belly of the beast, and now from beyond the grave.

It’s towards the end that gradually the breath becomes shallower, the pace changes. On ‘Prayer’ a single synth note fizzes just the right side of destruction with a left-right marching beat and somewhere in the background lurks a solemn organ drone. "Alleluia!" cries Vega. Final track ‘Stars’ is utterly haunting, with a chanting drone that might be a manipulated vocal as Vega offers a final lyrical testament that, like everything he did since Suicide played the first self-styled "punk mass" in 1970, is an affirmation that what might appear to be nihilism is not an emptiness but an imperative to create, to react, to push forward. It is directed, I imagine, as a message to his son, but of course it works for us all. "Do what you want… anything…" he croon/snarls; "The power is given…" and the final words he ever committed to tape: "It’s your life."

Frankie Teardrop has never ceased screaming. Alan Vega never surrendered. He couldn’t, it wasn’t in his nature. IT is not merely his epitaph but a living, vital, document of rage and hope.