Just over a year ago, I found myself having a conversation outside a relatively fashionable pub in Bethnal Green – not really a situation I relish; I’m one of those young-old types – with someone who worked in the music industry. It came to their attention that I was also peripherally connected to the sector, in as much as I write for the website you’re reading right now. This seemed exciting: "I just love music," they said. "But what music?" I asked, trying to nudge the conversation along. "Oh, I just really like music," came the reply. The discussion felt emblematic of something, although I couldn’t quite figure out at the time what it was.

Towards the end of Actress’ fourth, and potentially final, album, there is a song – or a snatch of a song – called ‘Don’t’. Clocking in at a minute and quarter, it consists solely of a looped, time-stretched, slightly chopped vocal sample (from Rihanna? An acid rarity?) imploring "Don’t stop the music" over a three-note keyboard figure which is only vaguely complementary. If there is a single track which serves as a key to deciphering this confrontational, challenging, moving, exhausting, complex and, ultimately, important record, it’s probably this. Ghettoville, it seems, is an argument for doing exactly the opposite to what the orphaned voice on ‘Don’t’ asks: it speculates, in ways which are alternately subtle and obvious, as to what the case might be for downing tools.

After all, in the current context, what is "the music"? Is it (clue: it’s not) an umbrella term for a connected, but benevolently antagonistic, ecology of thriving subcultures, or is it merely an abstraction which offers a reference point to the unimaginative, an appropriable signifier deployed to denote a more vaguely-defined creativity? Does "loving music" in London, in 2014, now mean anything more than collecting an armful of festival wristbands – shitty feathers in a metaphorical headdress – and heading to the local O2 every second Friday to get some culture?

Get to all the festivals you can. Never take your earphones out. Watch your playlist snake elegantly from The Lumineers to Emeli Sande, from Rudimental to some guy you saw at the local’s Acoustic Sessions and is definitely getting signed soon, from Nirvana Unplugged to Nouvelle Vague to Sigur Ros to some Northern Soul tune you heard on an advert and you "really, really like". Get on the street teams. Go to ‘gigs’; in fact, spend all your money on them. Make sure everyone knows you spend all of your money on them. You love music, love everything about it. But what you forget in this performed fit of inextinguishable amour fou, what gets neglected as this passion is fed at every conceivable opportunity, is that the love-music-alisation of this city, of this country, is precisely coterminous with the gradual erosion of music’s capacity to serve as a vector of political representation. What’s also forgotten is that this process is only part, albeit a potentially fundamental part, of a story about a crisis of political representation in general.

I’ve written about it so many times before, but the event seems absolutely central to what Actress, perhaps soon to be plain Darren Cunningham once again, is doing here. The riots of the late summer of 2011 were the symptomatic event par excellence when it comes to mapping cultural and political faultlines in a Britain caught in the grip of a reassertion of ruling-class authority. If that sounds a little melodramatic, there’s no better way of putting it. Despite various attempts to dress the disorder up otherwise, it was, completely, a consequence of the whittling away of popular democracy in the service of restoring traditional hierarchies. With this in mind, the last Actress album, 2012’s RIP, suggested a realisation that this was taking place; it drained techno of its last vestiges of collective euphoria, but retained its meticulousness to manufacture a sonic tableau of depressive clarity. In its starkness, it appeared to offer a window onto the way in which music as a force for resistance and critique has been absolutely co-opted and transformed into an easy lifestyle choice for the probably-never-vote-Tory-but-think-Boris-is-a-laugh classes. As with Burial or Zomby, it was a dream of rave, but it added to this oneiric quality an exacting, implicitly political, precision.

On first listen, Ghettoville is a departure in as much as this precision is more or less rejected as a strategy. Where there was palpably space around the notes on RIP, Cunningham’s follow-up plays with the crackle and distortion of early industrial music to flesh out the minimalism of his compositional skeletons. ‘Forgiven’, the opener, sets dragging, brittle electronic percussion and groaning pads against an atmospherics of meteorological threat and battlefield birdsound. As is often the case with Actress’ music – and with Burial’s, for that matter – the title gestures towards an emotional trauma which is not subsequently expanded upon, and the music itself provides no hint of the redemption the word suggests. The mood of black and bilious irony is set, then maintained by ‘Street Corp’, an assemblage of crunchy static and scant bass over which melodies dangle in a manner recalling those disturbing cot mobiles from horror films: the most comparable musical precursor is Geordie nightmarists Zoviet France’s 1983 ‘breakthrough’ Monohmishe, although there are also echoes of latter-day dysphorians like Silent Servant and Vatican Shadow.

There is no respite. With RIP, there was arguably a slight compensation in the fact that it seemed to have twigged what was going on: there’s always a slight elation when you work out you’re being done over. Ghettoville, however, details the aftermath of that epiphany, an aftermath which consists predominantly of the spreading awareness that epiphany in itself is not adequate. Take ‘Rims’, for example, which alternates a fuzzy, almost personable bassline with an unadorned drum loop which sounds as if it’s lifted itself off the studio floor in one last attempt to be ‘useful’ (it’s as if ATOS sent it in, in fact). The piece works as a structural allegory for trying – trying to think, trying to plan, trying to make, trying to resist – but being too tired: it’s a brilliantly sculpted justification for feeling half-arsed. Why make music, if ‘music’ has been reduced to the state of pure accessory or ornament?

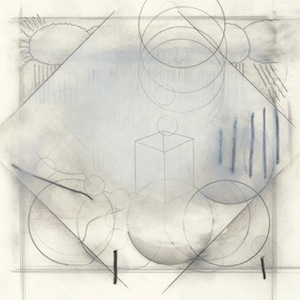

We’re all hauntological now, of course – seventy-five percent of mainstream pop appears to have summoned the spectre of early 90s dance at the Ouija board – but Ghettoville really gets to the kernel of the idea. In its own words, this is an album which captures ‘the artist slumped and reclined’, worn out by the ‘demands of writing’: this image, which could almost come from Edgar Allan Poe, points towards the fatigue brought about by trying to make music in a moment when it feels as if every possibility is co-opted from its inception. There is a sense of deliberate, knowing unfinishedness to most of the tracks collected here, a lack of completion which conjures an ambiguity as to whether the blanks represent a space which the future will redeem, or the absolute expiration of aesthetic and political potential. This is a record which exerts a demand upon everyone who listens to it, not simply in its abrasive textures but in the fundamental questions it raises about the worthwhileness of persevering.